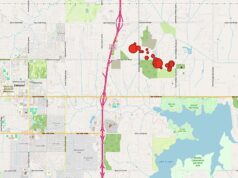

A 3.5 magnitude earthquake struck near Cushing on Tuesday morning, according to the United States Geological Survey.

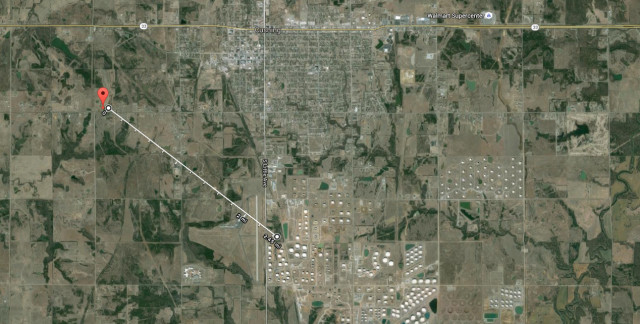

Cushing is home to the world’s largest crude oil storage facility and is often called the “Pipeline Crossroads of America.” One day earlier, Cushing was hit by a 3.0 magnitude earthquake. The epicenter for that quake was less than one mile from the site of the tank farms at Cushing.

According to the USGS, the epicenter of the Tuesday quake occurred at a depth of 4.3 kilometers. The quake occurred just 1.8 miles west-southwest of Cushing city limits and just 2.5 miles from the world’s largest crude oil storage facilities.

The tank farms at Cushing are operated by various pipeline companies. By some estimates, these storage facilities have a combined capacity of up to 76 million barrels. Some of the country’s largest pipeline operators own storage facilities in Cushing. Enbridge’s facilities there have a storage capacity of 20 million barrels. Plains All American Pipeline LP owns storage facilities that hold up to 12 million barrels.

Prior quake activity increased regulations

In October 2014, Cushing experienced 10 earthquakes in one week. Two of those quakes were greater than 4.0 in magnitude. Later that month, the Oklahoma Corporation Commission ordered a temporary shutdown of a nearby injection well that had been drilled into the basement rock. Currently, OCC only requires additional monitoring of injection pressures and volumes if an earthquake reaches a magnitude of 4.0 or greater and is within six miles of a disposal well.

Once that threshold is reached, OCC uses what it calls a “traffic-light system” to make determinations on the need for additional monitoring, according to my conversations with OCC staff and others aware of the process.

Other states have much lower thresholds for taking regulatory action. Critics of the traffic-light system view the policy as ineffective and symptomatic of the political climate. State agencies in Arkansas and Ohio have taken a less tolerant approach to regulating the oil and gas industry. Following earthquake swarms between 2010 and 2012, both states took strident measures to shut down culprit injection wells. Ohio and Arkansas have halted the permitting of any new disposal wells in areas prone to induced seismicity. Both states have also ramped up the reporting and monitoring requirements.

Such steps have given regulators the data they need to establish a definitive causal connection between wastewater disposal and earthquakes, and to shut down the culprit wells. Oklahoma is still taking baby steps.

Elsewhere, regulations appear to be working

Induced seismic events have dropped off significantly in Ohio and Arkansas since implementing new regulations. Citing an April 2015 report published by USGS, the New York Times reported that “in places where wastewater injection stopped, earthquake frequency fell to near zero.” That same USGS report shows that in Oklahoma, the quakes are just getting stronger and more frequent. According to the USGS, that’s mostly the result of “economic and policy decisions.” In other words, oil and gas activity and lack of political will to regulate it.

As the probability for more damaging earthquakes keeps growing steadily, industry’s control over Oklahoma’s state government could come at a high cost to public safety. Scientists and environmental advocates warn that, if a major quake does strike Cushing, damage to the state’s infrastructure, environment, and economy would be devastating.

Citing the effectiveness of regulation in other states, environmental leaders in Oklahoma continue to call for a moratorium on wastewater injections. OCC representatives and Gov. Mary Fallin maintain they don’t have the authority to impose a moratorium. Sadly, the Oklahoma State Legislature seems to be the best bet for those pushing a moratorium. For people living in areas most impacted by the earthquakes, the 2016 legislative session can’t come soon enough. State Rep. Corey Williams (D-Stillwater) and Rep. Jason Murphy (R-Guthrie) have both indicated they will call for a legislative hearing in the fall to explore legislative avenues.

Oklahoma remains cautious re: moratorium

While the governor, OCC and state seismologists from the Oklahoma Geological Survey have all cautiously acknowledged the role of injection wells in producing earthquakes, they’ve adopted similar talking points on the moratorium issue. As recently as April 2015, prior to leaving his position with OGS, state seismologist Austin Holland was still expressing skepticism that a moratorium on disposal wells would have any effect on mitigating the earthquake problem. Holland, who acted as a de facto spokesperson for OGS, has publicly admitted his own role in perpetuating scientific skepticism on the link between injection wells and earthquakes.

While OCC’s approach still remains cautious, Corporation Commissioner Dana Murphy issued a statement on Aug. 3 directing staff to proceed with plans to reduce injection volumes in the seismically active area of north-central Oklahoma known as the “Logan County trend.” OCC’s plan asks injection well operators to begin a gradual drawdown of wastewater injections in the area. The plan calls for a total volume reduction of 38 percent by Oct. 2. A media release from OCC states the reduction plan is the “latest development under the ‘traffic light’ system.” The plan also calls for plugging back some wells within the Logan County trend. The release suggests these measures will “bring the total volume for the area to a level under the 2012 total by about 2.4 million barrels,” noting the sharpest spike in seismicity began in late 2012.

Will it be enough?

In a phone interview on Tuesday’s quake near Cushing, OCC spokesperson Matt Skinner said the agency’s response would probably be similar to its response when the 4.0 quakes shook the same area last year. He did not rule out the possibility of OCC shutting down potential culprit wells, but said the response would also depend on the seismic data gathered by OGS. Skinner said OCC would be looking at any newly permitted injection wells in the area, checking on volumes for nearby wells, and making sure wells haven’t been drilled too deep, thereby hitting the basement rock. Skinner says the OCC has better faulting data today than they did a year ago, which the agency considers an improvement.

When asked about emergency response plans in the event a major quake did strike the Cushing tank farms, Skinner noted that wasn’t under the OCC’s jurisdiction. When asked, “who has the jurisdiction?” Skinner said he wasn’t sure. “I’ve never been really clear as to how that works,” he said.