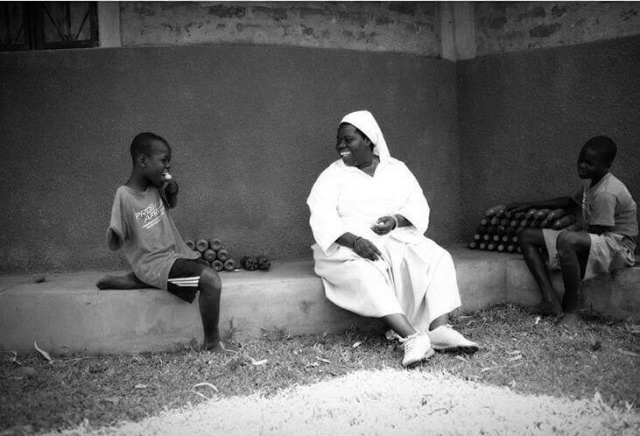

(Editor’s Note: NonDoc reporter Jack Fowler is also a musician, painter and a volunteer for the local nonprofit Pros for Africa. The organization supports Sister Rosemary Nyirumbe, who runs the St. Monica Girls’ Tailoring Centre in Uganda to provide shelter, training and hope to girls formerly held captive by Joseph Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Army.

Sister Rosemary is in Oklahoma this week to speak at the University of Oklahoma. She will also speak at 7 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 13, on the campus of Oklahoma City University. That speech is open to the public.)

I had been in Gulu, Uganda, for less than two hours, and I was already close to tears.

St. Monica Girls’ Tailoring Centre is a bustling, humming place, and I hadn’t endured 16 hours of coach next to the Smelliest Man God Ever Made just so I could loaf. I was there to help, damn it, and I was loaded for bear. But from every girl peeling lemons, from every clutch of shirtless men digging ditches or building huts, the answer was always the same when I asked if I could help them: a smile, and a soft “No, thank you.”

By lunch time, I was wondering if I’d made a mistake. I had three weeks (three weeks!) left of this little adventure before I could return to Western civilization’s loving embrace, and so far, I felt not only useless, but ignored. The little kids loved me with the visceral, manic glee that American children reserve for Santa Claus or Kevin Durant, but after recess ended and they went back to class, I wandered the campus alone like some pale ghost.

Sister Rosemary Nyirumbe is the founder of St. Monica’s and the burning sun around which the campus universe spins. She also might be the world’s biggest badass, so when she talks, I listen.

“You need to relax,” she told me over our lunch of Nile perch and matoke. “Don’t worry about working. You’re our guest. Do you go to people’s houses in America and start trying to work? I want you to just be here, and when you do that, your purpose will come and it will find you.”

Her advice felt like a warm bath. Almost immediately, I settled into the languid rhythms of African life, its slow breathing and soft speech, the time marked gently by sunrises and meals, both of which reminded me of Oklahoma but didn’t make me miss it. I peeled lemons. I washed dishes. I sat under trees and talked to new friends. I played with the little kids. My days were full.

One morning after breakfast, Sister Rosemary asked if I’d like to paint the chapel. A drab, leaking, concrete box for the girls to worship in every morning, it was long overdue for a face-lift, she thought. It was enormous, though. Even if I’d had enough time to finish it before I went home (which I didn’t), I wasn’t sure I was up to the task.

“I don’t want you to paint it,” Rosemary said. “I want you to paint on it. You’re an artist, and I want you to bring some joy into that room. I’m also bringing in an artist from Moyo tonight who wants to meet you. His name is Innocent.”

I took a bota bota into town, bought some horrible paint and worse brushes and immediately got to work. I spent the rest of the day painting an abstract mural that eventually circled the entire chapel, and I walked to dinner that night exhausted, but very happy.

I was greeted at the door by three small boys I’d never seen before, all of them beaming at me. One of them, the shortest one with the biggest smile, had no arms.

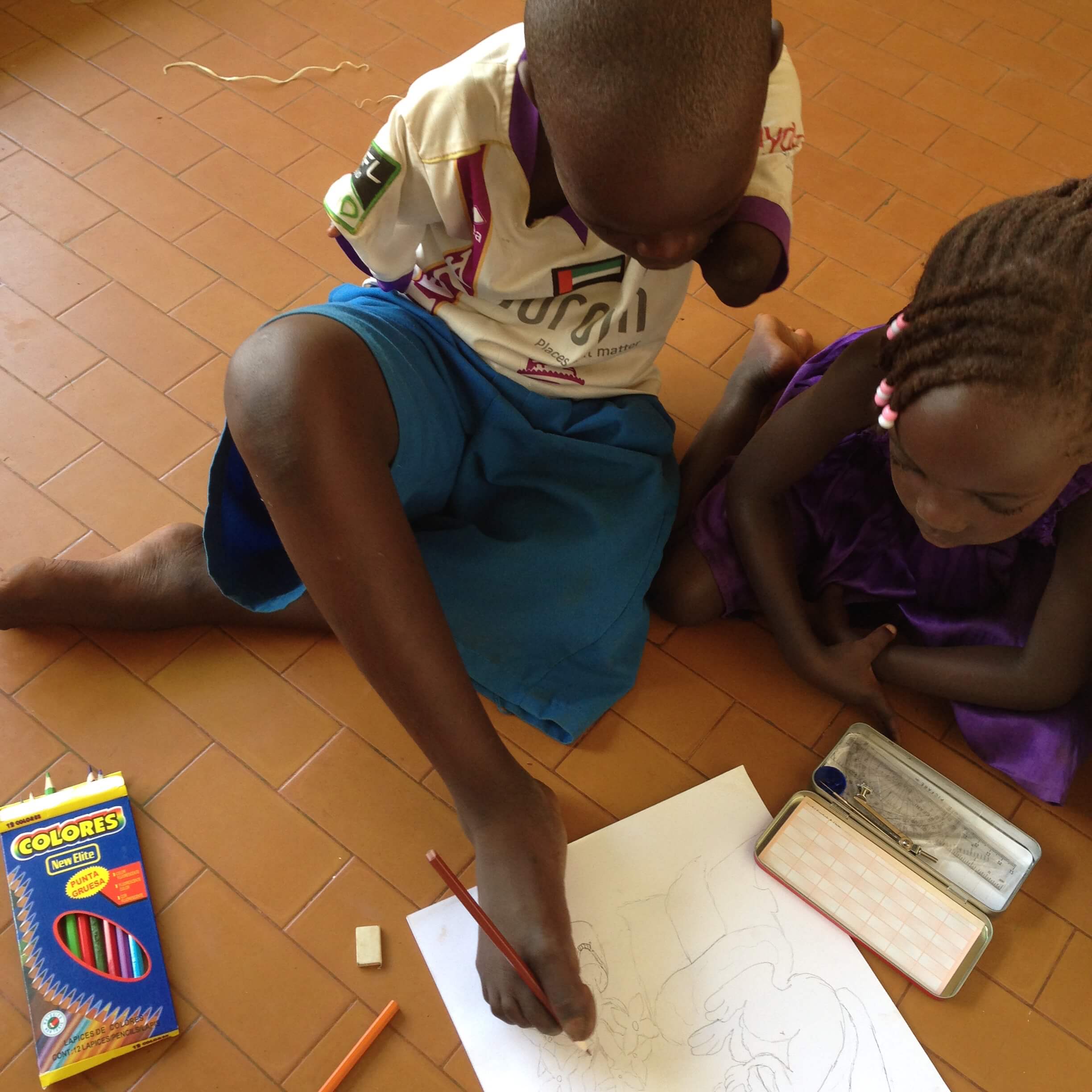

“Are you the painter?” he asked me. “I am Innocent.”

For the rest of that night, Innocent sat on the cold tiles of the dining hall floor and drew pictures for me, holding the pencil between his toes and sketching with the grace and skill of an artist twice his age. A chest of drawers, a monkey riding an elephant, a Fanta bottle (his favorite thing to draw), Innocent churned out piece after piece like there was money in it. He politely answered my questions as I sat in a chair and photographed him, amazed at what I was witnessing, but I could tell that when he drew, he was lost in it. After he finished each drawing, he’d grasp it between two toes and hold it out to me with his foot, beaming at me again. “For you,” he’d say.

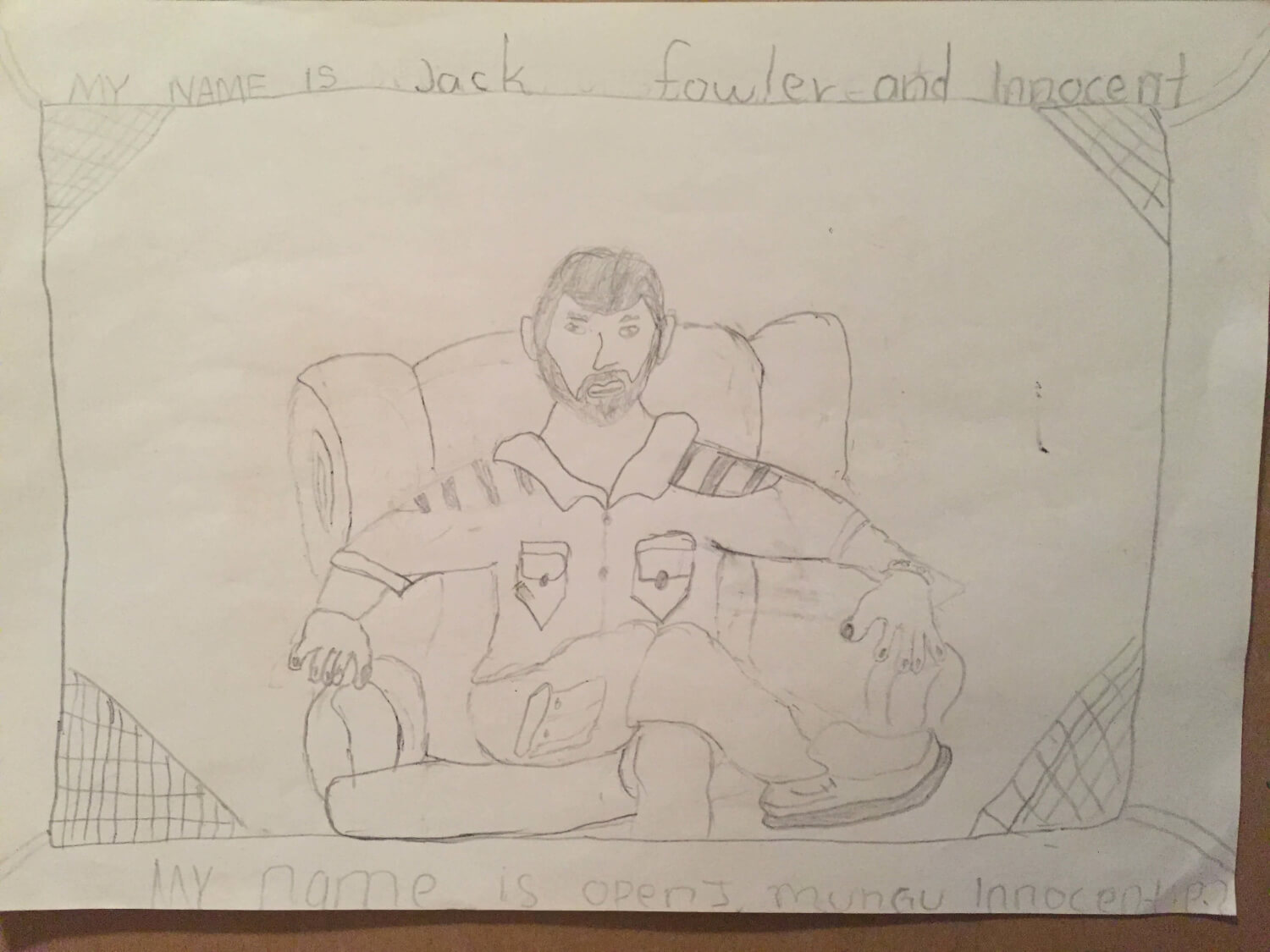

After breakfast the next morning, I was gearing up to start painting the mural again when Sister Pauline told me Innocent wanted to see me. I found him in the living room where the nuns like to watch soap operas, sitting on the floor, pencil in foot. “I want to make you a present before I go home,” he told me. For the next 30 minutes, I posed for my first-ever portrait. Innocent took his time, objectively eyeing me like a piece of marble, erasing and redrawing details with the focus of an air-traffic controller. When he was satisfied, he held out my portrait with his foot and smiled. “For you,” he said.

He’d drawn my fingernails and the wrinkles in my shirt, the cargo pocket on my shorts, the chair I was sitting in. He drew a frame around me like a classical oil painting. He gave me a full head of hair. And I had to choke back tears again as I realized I’d been busying myself in Africa the same way I had in America: making art and working with kids. Rosemary was right. My purpose came and found me.

I’ve got my portrait framed and hanging on my wall. I’d like to say it’s a reminder of something poignant, but I don’t need a reminder. Rosemary and Innocent didn’t teach me a lesson, they changed who I am. They showed me how to just be here.