After years of bad publicity, a controversial drug-rehab facility in southeastern Oklahoma associated with Scientology has been reorganizing operations. Some Oklahomans still want the public warned about the organization.

“We’re trying to revitalize and reorganize here, and we want to move forward,” said Robert Newman, senior director for public relations at Narconon Arrowhead in Canadian, Okla.

Arrowhead is the largest Narconon rehab center in the world, but it has been the subject of criticism, investigations and lawsuits stemming from the deaths of three separate people between October 2011 and July 2012.

Newman, a native of Elmore City who has worked with Narconon for 15 years, said he did not want to focus on past tragedies involving “students” at Arrowhead, but rather the thousands of other people who have attended the center and found recovery. After serving the organization in California and Hawaii, Newman returned to Oklahoma in November.

“That’s what I was brought in to do — to try to change the public perception,” Newman said. “To act like [the tragedies] didn’t happen would be like, ‘What the heck?’”

On Sept. 25, Narconon achieved a key part of its reorganization efforts in Oklahoma: certification of its educational program as a halfway house by the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services.

“The laws were recently changed, and we felt like, under these new certifications with the Department of Mental Health, this would be the best fit for [us],” Newman said. “These things we do and want to do as far as our program goes, [halfway-house certification] actually aligns pretty well with that.”

Senate Bill 295 was passed by the Legislature and signed by Gov. Mary Fallin in 2013. It was crafted with specific intent to address Narconon’s then-unregulated “education” program.

“Passage of SB 295 made it so that any provider already providing an ODMHSAS-certified treatment service is required to also certify any other substance abuse treatment service being provided at that facility,” said Jeffrey Dismukes, ODMHSAS spokesman. “In addition to maintaining certification of a non-medical detoxification program, Narconon Arrowhead was required to seek certification for all of their substance abuse programs offered on-site and subsequently elected to apply for and meet the minimum certification standards related to operation and delivery of substance abuse halfway-house services.”

Narconon has also sought halfway-house certification in Florida, but the Tulsa lawyer who is leading 11 lawsuits against Narconon Arrowhead in Oklahoma said the organization’s new halfway-house certification will only serve to expand their rhetoric.

“They’re pretty good at creating perception, I’ll put it that way,” said attorney Gary Richardson, who is representing the families of those who died at Arrowhead. He said one case has been settled.

‘We took it very seriously’

With its new state certification in hand, Arrowhead’s efforts to change public perception have involved other adjustments, including programmatic changes, protocol updates, website redesign and even architectural improvements.

“We’re going to be giving it a face lift, a redesign,” Newman said of the Arrowhead facility that overlooks part of Lake Eufaula and features a large portrait of Scientology-founder L. Ron Hubbard.

Arrowhead itself was originally a state lodge built in 1965 on a federal loan. Oklahoma defaulted on that loan, so the federal government took ownership and sold the lodge to the Choctaw Nation in 1985. In 2000, the Choctaws sold Arrowhead to Narconon, despite the group’s controversial ties to Scientology.

Narconon had established its first Oklahoma services in Newkirk around 1990 but needed to relocate owing to a dispute with Indian nations who had leased them an old school, according to an article in The Oklahoman.

Now, Newman said the space within the Arrowhead lodge is being adjusted to suit Narconon’s program capacity better.

“With our plans, we’ve scaled back quite a bit over the last few years. Now we’re going back up,” he said. “Part of our reorganization is to find out — with the facilities that we have — what’s [our capacity]? The truth is that we’ve had as many as 250. The demand for services, we (just had) people coming in in droves, and we unfortunately, you know, got big. We had 250 people at one time.”

A 2012 Tulsa World investigation reported that the international organization used more than 200 websites to help refer patients to Narconon, and Arrowhead CEO Gary Smith confirmed to the World that the facility paid finder’s fees to field representatives who refer patients there.

Newman said Arrowhead will have a capacity in the range of 112 beds moving forward.

“The truth is that we’ve operated at that capacity for a number of years, but when those things happened it was devastating,” he said of the patient/student deaths. “The management team took a look at everything, and they were like, ‘Wait a minute, what can we do to fix this to where this never occurs again because we’ve been here for 25 years and had not had anything like that happen. (…) We took it very seriously.”

While Newman said he has counseling certifications in California and Hawaii, he personally is not certified to provide treatment in Oklahoma. He said Arrowhead has about 45 people on staff, including about a half-dozen mental-health professionals: a medical director, an LADC, two CADCs and a peer-recovery support specialist. The facility also has several nurses.

Richardson, the attorney, suggested Arrowhead’s staffing levels are not always presented clearly to the public.

“If you read their advertising, you would assume that they have a medical doctor on the premises,” Richardson said. “When, in fact, the medical doctor is an hour and a half away and has his own private practice.”

Richardson was referring to Dr. Gerald Wootan, a doctor of osteopathy who runs a private family practice in Jenks. A call to his Jenks office confirmed he still runs that practice, and Newman confirmed Wootan is still Arrowhead’s medical director.

Newman said Arrowhead’s treatment (non-medical detox) and education (halfway house) programs cost about $30,000 in total and typically last between four and six months. He pointed out that many other addiction recovery programs may cost nearly that much for only one or two months.

Arrowhead’s website has also been redesigned within the past two months. Screenshots of the site taken Aug. 8 showed multiple pictures of young women in tank tops or strapless dresses smiling and laughing, but today the site features only photos of Arrowhead’s immaculate facility and its beautiful view of Lake Eufaula.

In addition, other information appears to have been removed from the site, including statistics that Richardson mentioned to NonDoc.

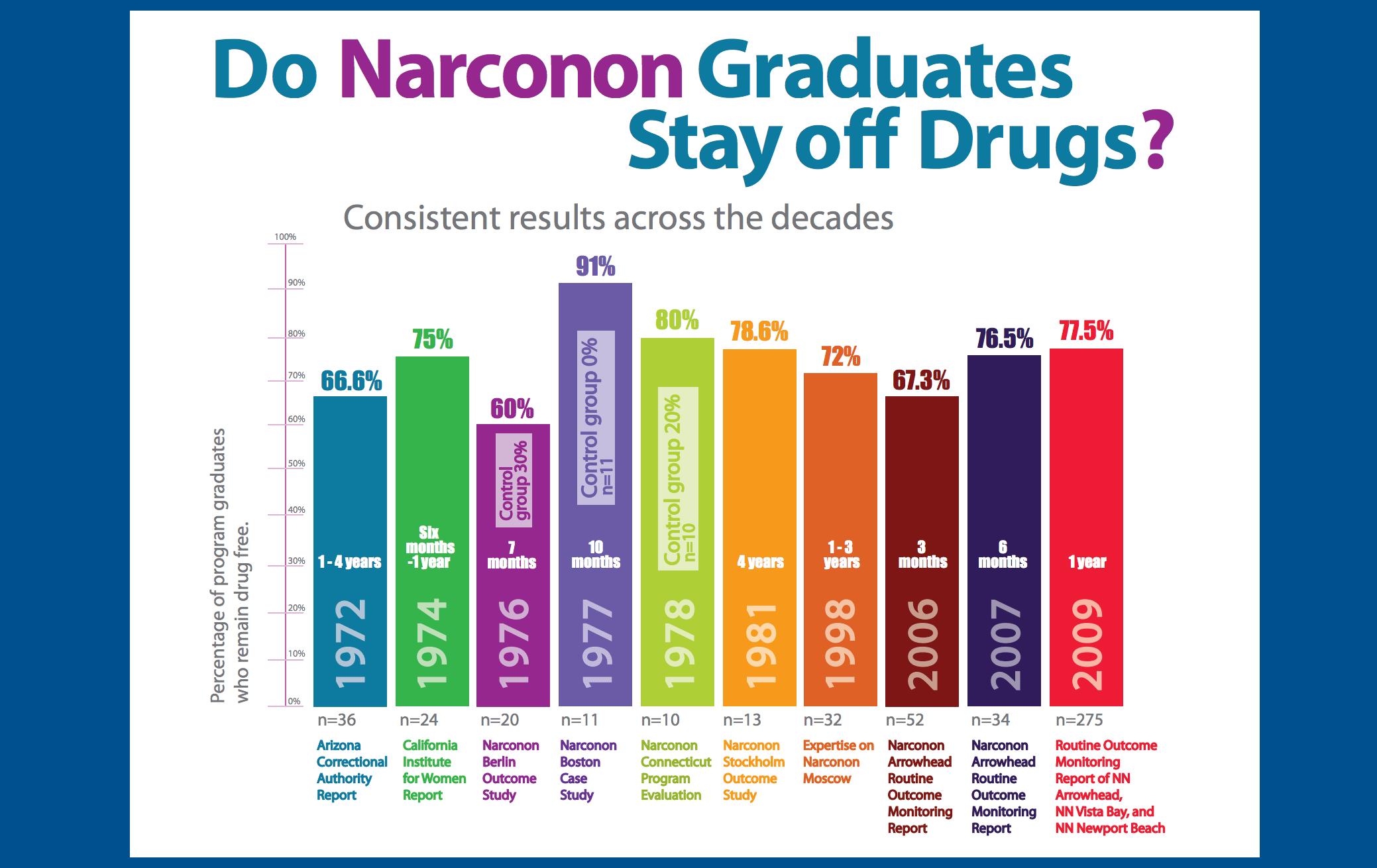

“When they claim to have the success rate that they claim to have — which is in the 70 percents — and you won’t find another rehab facility in the country that claims that kind of success rate, why wouldn’t you send your child there?” Richardson asked.

While Arrowhead’s website no longer appears to reference any quantifiable success rate at that specific location, a search using Archive.org shows a PDF on the site earlier this year featuring numerous bar graphs proclaiming enormous success.

Today, this page notes a 73.5 percent drug-free rate after six months for those completing a Narconon program, but it does not make specific reference to Arrowhead like the earlier PDF.

Richardson said he “will strongly contend that those numbers are not anywhere near correct.”

“If I had a child that had a problem with drugs, and I’d looked at their website and heard them tout what they claim to be factual, I very likely would send my child there,” the attorney added.

He doubled down and also critiqued Narconon’s past compliance with state rules.

“I’m convinced we will prove in the courtroom at trial that they did not comply with state regulations (in the past),” he said. “And I’m convinced we will prove that that’s what contributed to the deaths.”

Richardson also expressed concern about Arrowhead’s new halfway-house certification.

“In the midst of all that’s going on, I was quite surprised that they got a new certification from the state of Oklahoma for anything,” he said.

Dismukes, ODMHSAS’s spokesman, said minimum standards were met, implying the agency could hardly deny the application.

“ODMHSAS certification should only be seen as meeting these minimum standards and not an endorsement of philosophical approach,” Dismukes said. “Certainly, the consumer has a choice in treatment providers. We would encourage all Oklahomans to ask questions of providers related to all aspects of their treatment programs, and to be sure that the provider and services are the right fit for their situation.”

Of drugs and Scientology

“The drug scene is planetwide and swimming in blood and human misery,” said Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard in an essay posted on Narconon Arrowhead’s site. It also states: “Research demonstrates that the single most destructive element present in our current culture is drugs.”

Meth was the drug of choice for 30-year-old Samantha Downs.

“That’s what always took me downhill,” said the Missouri native who credits Narconon Arrowhead for saving her life. “But it always started with alcohol, and I couldn’t see that.”

Downs learned it while completing Arrowhead’s programs, she said. Newman passed her contact information to NonDoc as a former patient and student who could speak to the efficacy of Arrowhead’s programs.

Newman did not mention that Downs later worked at Arrowhead until earlier this year. She did, however, provide details about Arrowhead’s programs, beginning with the non-medical detox or “sauna program.”

“Basically, you start off your day, you go down to the sauna, and you take the supplement called niacin, and you start at a very low dose,” Downs said. “You take that in the morning and you do about 30 to 45 minutes of exercise to get your blood pumping and your heart rate up. Then you go sweat in a box.

“The philosophy, I believe, behind it is any time you put anything into your body — whether it’s Advil, Tylenol, drugs, pills, whatever it is — it breaks down in your body and it’s stored in your fat cells as a metabolite. And so Narconon believes that’s why cravings last so long, because when you start to sweat, one of these little bitty metabolites gets into your bloodstream and sends a message up to your brain that triggers you. So the sauna portion is to sweat all that stuff out of your body. It takes as long as it takes.”

After that, patients become “students” and enter Narconon’s educational program, which some have criticized as a way to convert people to Scientology.

Downs, who entered Arrowhead in October 2012, said she has “never been asked to go down that path or anything,” and she identified herself as a Christian.

Newman did not identify as a Scientologist either.

“I get people who ask me all the time, ‘I heard you guys were a recruitment tool for the Church of Scientology.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, if we are, we’re not very good at it.’

“We’ve had 11,000 people go through this program, and I maybe know — at best — maybe 30 people that have gone to look into Scientology services from there. The rest of them have gone on to their lives, gone back to wherever they came from, they’ve rejoined their families, what have you.”

Colin Henderson said he attended Narconon Arrowhead for about 10 days in July 2007 before leaving. After his experience, he began efforts to raise awareness about what he says is the organization’s true mission.

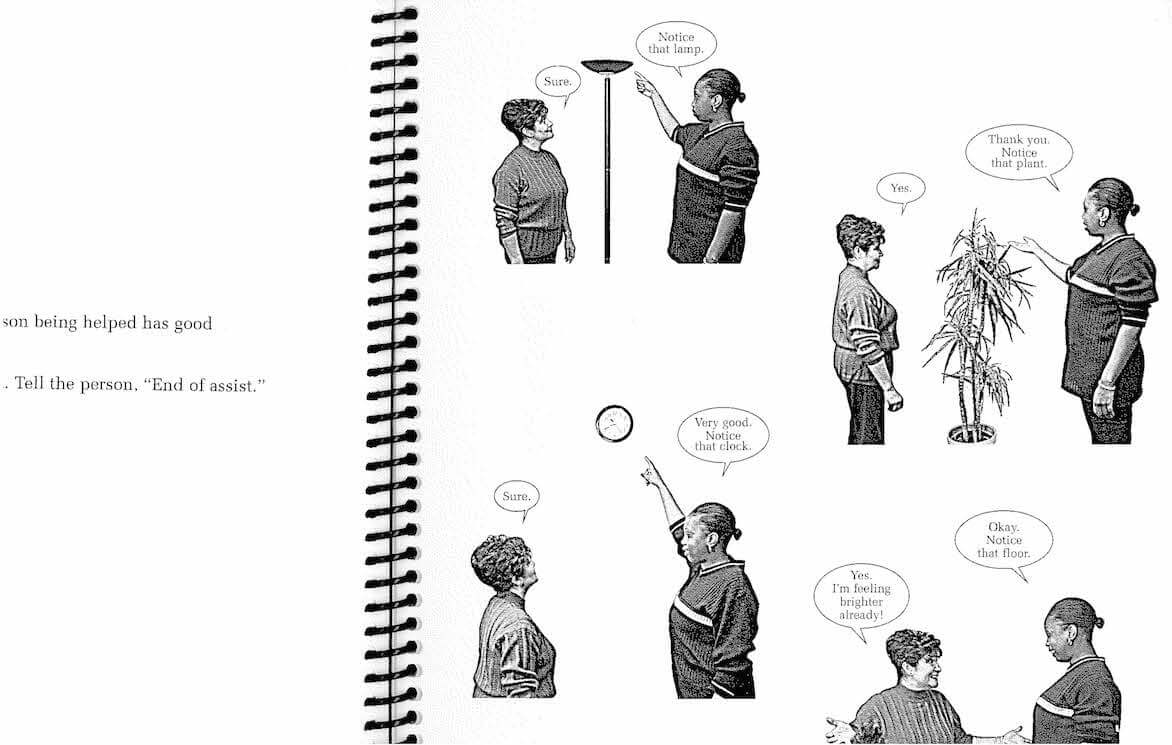

“I was promised Scientology has nothing to do with this, that or the other, when in fact it was 100 percent a Scientology training routine from the get go,” said Henderson, who was addicted to oxycontin. “You go all the way up this [training routine], talking to ashtrays, all that kind of stuff.”

Henderson said he did exercises where he was supposed to stare at another person without blinking for extended periods of time. He said the exercise eventually freaked him out and he demanded to know what was going on. Eventually, he said a man brought out a book and explained what a “thetan” is.

From Scientology.org:

The thetan is the source of all creation and life itself. It becomes fully apparent for the first time in Man’s experience that the spirit is immortal and possessed of capabilities well in excess of those hitherto predicted.

The exteriorization of the thetan from its body accomplishes the realization of goals envisioned but rarely, if ever, obtained in spiritualism, mysticism and such fields.

Newman contends that all potential patients/students are given a clear orientation about the programs they are entering.

“They actually will sign the admissions paperwork stating they are aware that we do use the rehabilitation methodology that was developed by L. Ron Hubbard,” Newman said. “It’s basically based off of life-improvement techniques or drug-rehabilitation techniques that were developed by L. Ron Hubbard. It’s not like, oh well, we’ve got Scientology, and now we’re going to use Narconon, if that makes sense. But there is a connection.”

Newman framed Narconon’s education program a different way: “If you look at addiction as a disability, you can actually increase your abilities to overcome that.”

Downs said that’s exactly what she did.

“At Narconon, they called it realizations or gains that you were having (…) cause they’re all personal,” she said. “That’s one thing that I really loved about the program that was different than [Alcoholics Anonymous] or [Narcotics Anonymous]. It was about what I was getting out of it.”

Henderson said what he got out of it was a mission to help raise public awareness about the issues surrounding Narconon, even helping some people get out of the facility.

In his personal experience, Henderson claims his blood-pressure medicine was withheld from him until he threatened to call his lawyer.

“Then they went and found my prescriptions that they said they couldn’t find and started handing me one every morning,” Henderson said.

Newman said that sort of thing does not happen at Arrowhead.

“Probably the biggest misconnection is as far as the medication goes — that we don’t believe in medication,” Newman said. “Well, that’s not true. Our medical staff is licensed with the State of Oklahoma. They are going to follow that protocol. (…) If the person is not qualified to do our program for medical reasons, we’re going to recommend a higher level of care.”

Henderson said he wound up seeking individual counseling for his addiction issues and the experience at Arrowhead.

“You go through something like this, it’s pretty hard to trust another rehab.”