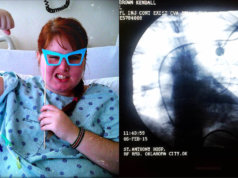

Wink Burcham has a bum knee, a woman who loves him and a daughter younger than the new year.

Ali Harter has a car that is destined for the junkyard, drives her daughter Bonnie to pre-kindergarten five days a week, loves her man Wink and just birthed the same newborn child.

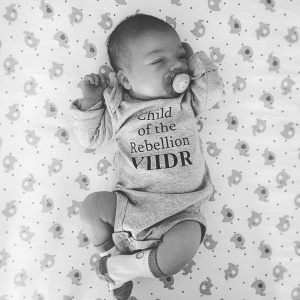

Ryland Faye Burcham came into their world on Jan. 3, weighing 8 lbs. 5 oz. As Harter announced on Instagram, “Completely perfect. We did it!”

Life is good.

Because Wink, 33, and Ali, 31 — as they are known when they perform all over Oklahoma together and separately — have been full-time working musicians for more than 10 years, Ryland is considered “red dirt royalty” among their Oklahoma music friends and family.

She is also one of more than 30,000 children whose pre-natal care, birth and first year of medical coverage are taken care of by SoonerCare — Oklahoma’s version of Medicaid, the program that helps pay some or all medical bills for many people who can’t afford them. In fact, this program pays for nearly 60 percent of all live births in Oklahoma, and some form of Medicaid pays for more than half of all births in the United States.

Luck and prayers

“When we got pregnant, with just our income, I qualified for SoonerCare,” Harter said. “Right now, Ryland and I are on SoonerCare, and I pay for her [Bonnie] to have insurance with a subsidy so it’s affordable.”

In its 14th annual 50-state survey of Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost-sharing policies released earlier this month, the Kaiser Family Foundation reported that Oklahoma is one of 18 states that covers pregnant women up to 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (or $11,770) in 2015.

Under federal law, a newborn whose mother who is enrolled in Medicaid at the time she gives birth is deemed eligible for Medicaid until age 1. Oklahoma has expanded that program through an online enrollment system that ensures newborns’ automatic eligibility translates into actual enrollment in SoonerCare as soon as they are born, without delay.

“For me, my insurance runs out at my six-week checkup, and so after that I’ll have to worry about something,” Harter said. “For her [Ryland], she’s on it for maybe a year or so after birth, and then I have to worry about getting her covered.”

Even that is not so simple. Her 4-year-old daughter Bonnie had health coverage through Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Oklahoma in 2015, but at some point last year, her primary care physician was no longer “in network” under the policy for which Ali was paying. After receiving a bill from the doctor that she thought was covered, Harter decided there was no reason to pay those premiums to the insurance company if visits to her daughter’s doctor were no longer going to be paid properly.

“I just didn’t pay Blue Cross and Blue Shield for the last month or two of the year,” said Harter. “We tip-toed around and we were very careful not to get sick or hurt for the last couple of months. Now, she’s covered under United Healthcare because I had to find somebody who had her doctor in network.

“It’s a mess.”

Burcham’s insurance situation is less complicated.

“He has nothing,” Harter said. “Basically, he’s been lucky so far, but we have to figure something out.”

“I just pray that I don’t get hurt or sick,” Burcham chimed in.

Had Oklahoma expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, Wink likely would have been one of nearly 100,000 Oklahomans covered at low or no cost.

On Dec. 20, less than two weeks before Ryland was born, the pair opened for John Fullbright at Cain’s Ballroom in Tulsa. It’s the kind of gig that potentially can put a musician on the map, and certainly one you want to play right before you must take six weeks off to have a child.

But earlier that week, Wink’s bum knee flared up, and eventually Ali convinced him to go to the emergency room. The final bill ended up being around $500 for a knee brace and prescription painkillers that consumed most of whatever they made from that gig.

As part of the estimated 17 percent of Oklahomans without health insurance, the couple paid for that emergency room visit out of pocket, and Wink made that gig at Cain’s because they have a growing family to feed.

For the last three months Ali was pregnant, the pair played non-stop at every venue that would have them, because musicians in Oklahoma don’t get maternity leave.

“I’ve done my very, very best to get active again so I can work, because I have to. I could only afford to take January off,” said Harter. “That was the plan, until she came out, and until my doctor told me to stop — just work my butt off, and take every single thing that we could. We have to.”

Red Dirt Relief Fund offers support

Because the couple knows practically everyone in the Oklahoma music scene, those gigs at the end of the year before Ryland was born also involved a lot of baby showers with gifts, along with some assistance from the Red Dirt Relief Fund — a nonprofit made up of musicians who help each other out in times of need.

“We’d never in a million years have thought to [contact Red Dirt Relief Fund]. So when they approached us, it was a huge weight off our shoulders,” Harter said. “I had saved a little bit, and he was going to play twice as much to cover what I couldn’t play.”

The pair has played benefits for the organization, including the annual Gypsy Cafe fundraiser in Stillwater honoring Bob Childers, who died in 2008 of emphysema and lung disease. Since 2012, the Red Dirt Relief Fund has donated more than $30,000 to help musicians and their families through hard times — raising more than half from that annual benefit.

the world keeps spinning round.

We’ll do our time,

and we’ll go dancing home.

— Wink Burcham, We’ll Go Dancing Home

$100 per man

Being a musician in Oklahoma is not a recipe for being rich. The good gigs may pay $500 per person, but there’s an unspoken offer of “a hundred dollars a man” that drives many transactions and has for years.

“A hundred per man has been standard for a while now. But it’s starting to feel like that’s not enough,” Harter said.

After an hour drive to Tulsa, three hours playing and an hour driving back to Oklahoma City, at $100, it works out to about $20 per hour. That doesn’t include instruments and related equipment, transportation, food, lodging or the lifetime of experiences that go into those songs.

Both musicians also have albums that are nearly ready to be released, but each is awaiting funding.

Ali’s recording has been mostly done for more than a year, partially funded by her Kickstarter campaign. But the cost of recording the album exceeded what was raised, so now it’s a matter of coming up with the balance to pay back the funders and release the CDs, vinyl and digital recordings so it can begin funding her music career and family needs again.

“That record went through a divorce, went through several deaths, it went through births. It took forever, but we’ve come up with something awesome,” she said.

Wink’s album is also mostly done and will be released in Europe in April before his third tour there. But he, too, will have a Kickstarter campaign (pending on a video pitch) so it can be finished and released in the United States.

Getting those recordings into the hands of fans will help fund the couple’s share of the USDA’s estimated quarter of a million dollars it costs to raise a child to the age of 18.

Living in crisis

Like most Oklahoma musicians, Wink and Ali have other jobs, too: Ali has the Pigs Fly Shop on Etsy and a hostess gig at the Barrel in Oklahoma City; Wink does odd jobs (including mowing lawns, which generated a blues song called Lawnmower Man) when there aren’t enough music gigs that put food on the table and pay the bills.

Like many Oklahoma families, Harter and Burcham live in crisis.

“I’m getting ready to sell my car pretty much for scrap because it died,” Harter said. She’s looking for a replacement that’ll be reliable and help traverse the miles they travel each year playing music for money.

At the end of the day, Wink Burcham and Ali Harter are just regular working people. They do what they have to do because kids are expensive and simply living is, too.

Fortunately for them, happiness is not.