Once upon a time, Oklahoma was considered a liberal (if not radical) place. It had a progressive constitution designed to make government responsible to the will of the people; and it was offered by some students of politics as a model for other states to follow. Once upon a time (1912, I think it was), Oklahoma had more registered Socialist voters than any other state in the Union.

And there is the context in which to consider some Oklahoma writers who emerged in the 1930s.

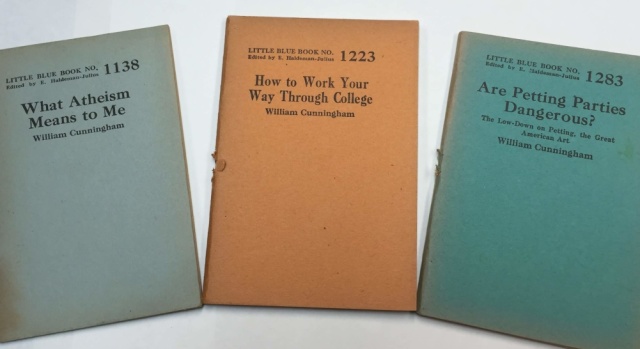

One of them was William Cunningham, born in Okeene in 1901. He grew up in Watonga and attended the University of Oklahoma, receiving a degree in journalism, a profession he pursued along with teaching high school.

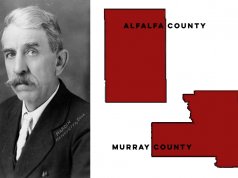

His daddy was a Eugene V. Debs socialist, and Cunningham, along with his sister Agnes (born in 1908 and known as “Sis”), turned out a shade or two beyond pink, even in the middle of the infamous “Red Scare” of the 1920s. For a few years in the early 1930s, Cunningham taught at Commonwealth College in Mena, Ark., an institution established to teach farmers and others of the social underclass how to deal with fat cats by being radical about it. He roundly damned lawyers, bankers, businessmen and Bible-thumpers for their prejudices and their stupidity; and he damned populist governors like Ma Ferguson (Texas), Huey Long (Louisiana), and Alfalfa Bill Murray (guess where) for their membership in what he called the “moronic minority.”

In 1935, Cunningham published two novels. The first, The Green Corn Rebellion, was ostensibly a story based on the abortive attempt by some Oklahoma farmers to protest American involvement in World War I (and coincidentally their draft status) by marching in the general direction of Washington, D.C. In reality, it is a rural burlesque about what can happen when hayseeds try their hands at politics. The second novel was Pretty Boy, a slashing piece of work debunking the home-grown myth of Charles Arthur Floyd, who was hardly the hero his Cookson Hills cronies had made him out to be. Both novels painted a picture of dimwitted, gullible bumpkins who were victims of their own ignorance as much as they were manipulated by the rich and powerful’s base stupidity.

And 1935 was also the year that William Cunningham became state director of the W.P.A. Writers Project in Oklahoma. He ran it for three years, departing Oklahoma in 1938 for a job as assistant to the national director of the Federal Writers Project in Washington. When Zoe Tilghman, widow of famed Oklahoma lawman Bill Tilghman, was not named by Cunningham to succeed him at the state level, she began to raise all sorts of hell: Cunningham was a Commie symp author, he was an organizer for the Communist Party, he wrote Communist propaganda, he raised money for the loyalists in the Spanish Civil War, among other possible sins.

Old Zoe was in such a snit that she spent a great deal of time writing to Texas Congressman Martin Dies, chairman of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, contending that her exclusion from a leadership position in the Oklahoma project was surely the result of commie plotting.

Regardless of what the locals may have thought of his politics, William Cunningham accomplished much for Oklahoma as head of the state writers project. Under his direction, most of the work on the “W.P.A. Guide to Oklahoma” was completed, as were compilations of slave narratives, and, among other things, a Comanche dictionary and a study of early Indian missions in Oklahoma.

Cunningham stayed in Washington for a couple of years, then moved to New York, where he worked for the Soviet news agency TASS from 1940 to 1948. As the Cold War warmed up, Cunningham evidently cooled down, publishing only two more books before his death in 1967. One was a novel co-authored with his wife, and the other was a biography of Daniel Boone for juvenile readers.

Sis Cunningham attended Commonwealth, was a member of the Red Dust Players, and performed agitprop theater for rural folk across Oklahoma in the 1930s. Some have called her the “female Woody Guthrie.” In the 1940s, she was in Detroit working for the Communist Party; and a decade later, she was active in helping to bring about the folk music scene in New York. She was a songwriter of considerable talent, and of her songs, How Can You Keep On Moving (Unless You Migrate Too?) is a Depression-era anthem without equal. Sis died in 2004.

William Cunningham won’t be in the textbooks, and if you cannot grasp why, re-read the foregoing or ask the nearest state politician.