I always knew I was African American. In my household, we were black people. Descendants of slaves, yes. Also descendants of Native Americans and Irish. We were black.

The classics weren’t only defined by Shakespeare, Frost and Hawthorne. Classics included Baldwin, Hughes, Hurston and Douglass, and in many ways these jewels were more valuable. They were our stories and our narratives — written by us.

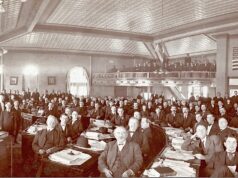

I remember the first time I had a clear understanding of the tales and photos of the Jim Crow era; of what that would have meant for me had I lived then. The concepts of separate water fountains, white-only restaurants and colored-only entrances were so foreign to this child who attended a white private elementary school from kindergarten to third grade that I always had questions.

When I asked my mother, a native of Oklahoma City, about her experience with segregation, she would pause and say she was protected as a child by her community and parents. She lived on the east side of Oklahoma City in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s where most stores and restaurants were owned and/or operated by black people. Later, she experienced directly racist interactions with white people, primarily when she went to college as an adult.

My mother said my grandmother would go downtown to the segregated John A. Brown department store to get dresses for her daughters so they didn’t have to experience interactions meant to emphasize how they were colored and not as important as the white girls.

I asked my father about segregation. He was from Cincinnati, and he despised integrated schools. That’s because, in the ’50s, he attended them. He didn’t recount many stories with me, but his message was clear. Integration was a double-edged sword. Yes, we had rights that would elevate us, but we also lost our sense of accomplishment and independence. He said in many black communities, we had everything, until we didn’t. I wanted more details. He wouldn’t give me many, mostly just stories about all the things in his hometown that reinforced community, love and self-reliance.

Many years later, after 9-11, my parents and I were going onto Tinker Air Force Base, and it was high alert. At the gate, everyone in the car had to show ID. When my father pulled up to the gate, I checked my purse and couldn’t find my license. The young, white military guard asked for ID. My mom gave hers, then my dad gave his, and I advised the attentive soldier that I didn’t have mine. He looked at my dad’s ID, straightened his back, saluted and said, “Will you vouch for her, sir?”

My dad replied, “Yes, she alright,” as cool as ice.

I looked at my father and asked, “Who are you?” He was a retired chief master sergeant. I learned later what that meant, particularly for the era during which he served.

Eventually, I realized I came from a house steeped in pride, resistant to the common imagery of black people being “less than” in any way.

It can be difficult to reconcile with the mainstream media’s portrayal of black history.

Traumatized DNA: ‘Your name is Toby!’

I still had questions about how black history was often presented in lieu of the excellence I was educated about by my family. Where, I wondered during my school years, are our images and stories that include the physical fight for freedom, particularly during slavery?

In 1977, the groundbreaking miniseries Roots offered Americans a visual reminder of the most inhumane part of post-colonialism in the United States: slavery. More than 300 years after about 12 million Africans were brought across the Atlantic Ocean against their will, we sat on our couches and watched Kunta Kinte get captured, smuggled, beaten and dismembered. The scene where he is whipped into saying his name is “Toby” traumatized my ancestral DNA in bright technicolor.

When the miniseries originally aired, I was too young to watch, but in the late ’70s and early ’80s, Roots was mandatory viewing if you were a black child older than about 11. Our elders would tell us we needed to know what we overcame. Yes, we did. Roots was the first time we saw how slavery actually played out day to day.

I remember watching and thinking, “If they have all the tools and are blacksmiths, why don’t they just kill the masters and run? Why don’t the cooks in the house slowly add finely grated glass to the food, as generations of black women were told how to do? Where was the plan of escape that I’d read about in narratives? Where is the rebellion? Was I to believe that, as a people, we were so weak that we just accepted brutality and subjugation with humble hearts?”

That portion of my history as a black person wasn’t in line with the stories of rebellion I’d read — about Nat Turner, Harriet Tubman and free black men and women who fought and killed for freedom. I had read slave narratives about love, how freed slaves would return and be sold into slavery to be reunited with their wives or husbands. We loved very deeply. Our family unit was extremely valuable to us. So was freedom.

But Roots in 1977 didn’t have that part of our history.

New ‘Roots,’ ‘Underground’ expand vision

Fast-forward to 2016, and Roots has been re-imagined. In the new version, there is more detail about the village in which Kunte Kinte grew up, and, to expand the vision of Alex Haley’s Roots, other elements were added as well, such as the possibility of studying at the university in Timbuktu, African traditions of music and dance being passed down through generations, and former slaves’ participation in the Civil War. It’s a remake worth watching.

The year 2016 has also produced a historic series with a slave narrative titled Underground on WGN. Prior to it, I do not recall seeing a television show or film in the modern era about rebellion, revolt and the desire to be free.

Underground examines slavery’s complexity from the slave’s perspective. It’s more than just light complexion versus dark complexion, being in the house or in the field. There were choices to be made to live as safely as possible (if that was possible at all). The desire to protect one’s children and keep them out of the field was paired with the envy of watching from the big house as other women could go and be with their husbands and families.

These sentiments are described so eloquently by the character Ernestine in the world of Underground where thoughtful, powerful and complex human beings fought for freedom. Mothers and fathers killed and died for their children, and the lead male character sacrificed his own freedom for the woman he loved. It has been powerful to watch. These were the slave narratives I wanted to see years earlier.

‘Creative projects that capture our full experience’

Still, for some African Americans, Underground is just another movie where black people are in chains as slaves. The visual of oppression without other stories to counter captivity can weigh heavy on the souls of those who are still fighting for equal protection and access today.

We were and are more than just slavery, but that portion of our history has to be told. This is American history, and we cannot forget what happened. Slave narratives aren’t the problem. A lack of creative projects that capture our full experience is.

This year, a much anticipated film about Nat Turner — The Birth of a Nation — will hit theaters in the fall. In 2017, a film called Hidden Figures will be released about African-American mathematician Kathrine Johnson and rocket scientist Annie Easley, who both worked at NASA. Between the two movies, one is a slave narrative like we have never seen on the big screen, and the other is a story about black women who aren’t entertainers or domestics. Together, they will help present a more full black experience.

There is absolutely no shame in any part of our history. There is, however, a demand that our history be relayed accurately by people whose ancestors lived it. In my opinion, the next film depicting our history should be about Tulsa — a true story of the wealthiest black community in the country being bombed by the United States government in 1921.

No chains, just the fight for freedom in the face of oppression. Rebellion. Liberty. Freedom.