I think the headline says it all. Julian Assange is a coward.

It’s not just that he’s avoiding extradition to the U.S. It’s more that he’s avoiding a charge in Sweden for rape. It’s not that he is a “political prisoner.” He isn’t. Julian Assange is a prisoner of his own self-importance, one that has built up a cult of personality centered on his existence in the “movement” he claims to have built.

What has he accomplished? Not as much as he believes. Not as much as he wishes.

Secrecy facilitates compromise

Secrecy in international affairs is not a bad thing. Assange would have you believe otherwise, but it’s simply true. Secrecy is how diplomats make deals. Deals that stop big wars. What about if, instead of sending letters to the White House during the peak of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Nikita Khrushchev had tweeted the letters that provided both sides the off-ramp that averted a nuclear war and end of the world? Imagine the grandstanding if the Iran nuclear negotiations had been shown on C-SPAN, as Iranian diplomats were forced to play to nationalist audiences in Tehran and Secretary of State John Kerry became hostile under intense congressional pressure and outrage.

Secrecy allows diplomats to stick their necks out, to find hitherto unknown points of mutual agreement, to make the compromises that prevent conflicts.

The failure of ‘democratic’ diplomacy

After World War I, President Woodrow Wilson proposed a new kind of diplomacy that would negotiate openly, “democratically,” he thought. He thought that the cause of the Great War, as World War I was then known, was secret diplomacy. He saw the telegrams between Berlin and Vienna during the July Crisis before the war, or the Zimmerman Telegram to Mexico, as being indicative of the kind of mindset that led to war; secret plotting to punish Serbia for the death of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, or secret deals like the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that ended the war’s Eastern Front. Democracies, Wilson believed, wouldn’t go to war. Their citizens wouldn’t allow them to. Therefore, if countries negotiated openly, together as equals, we could effectively end war. Couldn’t we?

No, is the short answer.

There is, of course, nothing wrong with the freedom of information. It is the right of all citizens in a democracy. But where sensitive matters of national security are concerned, there is a reason why these things remain secret for a number of years: Where they concern the lives of our operatives abroad, where they concern our national security, sensitive matters between allies, or matters of war and peace, secrecy and discretion are of course good and necessary things.

Assange asserts selective openness

Julian Assange claims to profess that belief, that people have an absolute right to know everything that their government is doing, especially in the realm of spying and foreign affairs. But I don’t think that’s what Assange really believes. Assange doesn’t believe in the openness of governments around the world, or at least, in every government. Only those governments he doesn’t like. Only those politicians he doesn’t like.

Take, for example, the leak of a mass of unverified, possibly-tampered-with emails from Hillary Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta. How could Assange be so sure, as he claimed to be, that these emails where 100 percent authentic? How could he know that if he did not know his source on the diplomatic cables leak (the leak from Chelsea Manning) until her name was published by actual news organizations? How could he know that the source of the Podesta emails was absolutely not the Russian intelligence services, as he claimed in his interview with Sean Hannity?

Only as good as his word

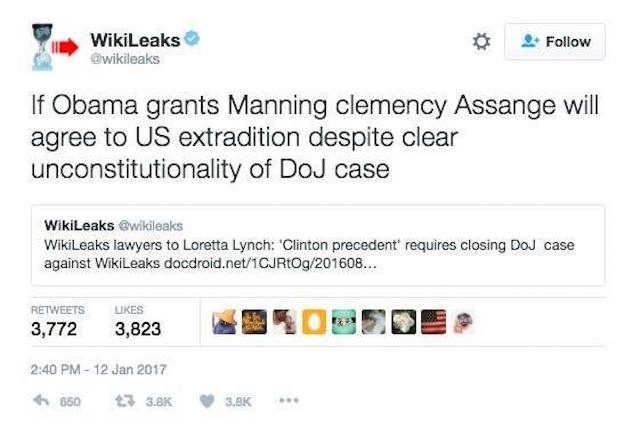

On Jan. 12, Assange tweeted a claim that he would agree to face extradition to the U.S. for trial on the condition that President Barack Obama first pardon Chelsea Manning.

Mr. Assange — Julian — you made your offer on Twitter without further condition.

Now that President Obama has done that, I look forward to seeing you make good on your pledge.

Come to the U.S. and stand trial. I promise that the trial you get here will be imminently more fair than the trial you’d get in the courts of Tomsk or Vladivostok.

But I suspect you are a coward who will not keep his word.