A practice known as domain slamming recently targeted the digital inbox of one of NonDoc’s email accounts.

A spam filter detected the suspicious message Friday and flagged it for review.

Basically, the sender was “alerting” us that a company in China had sought to register NonDoc under the China-based .hk and .cn top-level domains (TLDs). In the interest of protecting our brand, the sender offered us the “opportunity” to beat the would-be infringers to the punch and help us register our own Chinese sites as soon as possible.

Unlike most spam, the email was actually well written (regrettably, I had already deleted it before conceiving of this article). It also had an official-looking signature from “Bryan Chang”. Plus, the idea of protecting NonDoc against infringement appealed to me at first.

Still, something about the email seemed fishy, especially since it was already flagged as spam.

From phone slamming to domain slamming

The email we had received was the first step in a domain slam. While it tried to play on the fear of our brand identity being under attack, other emails, using official-looking letterheads and spoofed email addresses, will simply try to convince the user their registration is expiring and must be renewed.

The scam has its roots in the long-distance oligopoly of the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. At that time, guerilla marketers aggressively sought to siphon revenue from AT&T, Sprint and MCI. Generally, AT&T is credited with coining the term “slamming” during this period to describe “the unauthorized switching of customers” from their service to a competitor’s.

This switching was also illegal. Perhaps the victim thought they were registering for a drawing or signing up for something else, but the fine print in fact contained pernicious catches. By 1997, Knight-Ridder reported that telephone slamming complaints filed from consumers to the FCC had quadrupled since 1994.

As the world-wide web gained traction into the 21st century, scammers transposed their techniques from phone customers to registrar customers. Instead of switching consumers’ phone providers unbeknownst to them and against their will, domain slammers seek to switch a website owner’s registrar (e.g. from GoDaddy to their own). As one might expect, this winds up costing the consumer more. Worst-case scenario: The business could have its entire online presence hijacked and held for ransom.

In 2011, a Seattle-based law firm described on its Chinese law blog how domain slamming was about to increase. At the time, ICANN, a regulatory body that oversees online protocols and standards, was opening up TLD registration for non-Latin characters. A few years later, China’s version of ICANN announced .cn registrations were public.

Don’t fall for it

If you’re a business owner with a commercial website or otherwise have a stake in the binary battleground of domain registration, you should be wary of domain slamming.

Although around, in some form, for two decades, I had never heard of slamming at all. (It’s actually the predecessor to spamming, which appears more recognizable because it can target more people for less specific reasons.) It only crossed my desk last week because of my administrative role in the guts of this site.

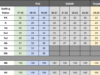

France-based Internet protocol and intellectual property firm Systonic has compiled a list of purported Asian companies involved in domain slamming. (It’s rather large but only as recent as 2014). This could come in handy in cross referencing suspicious emails you receive.

For the more proactive, the managing editor of tech site MakeUseOf.com includes a guide for registering your site in China. It’s near the end of his comprehensive account of a typical slam attempt.