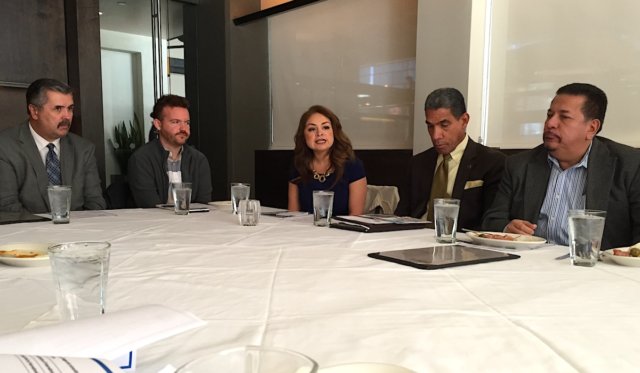

With two dozen Oklahoma stakeholders gathered Wednesday around a table at the Broadway 10 chophouse, congressional field staff and media heard about “the fear” facing families who await congressional action on the United States’ DACA immigration policy, which predominantly affects young immigrants who are students.

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program was created in 2012 by then-President Barack Obama’s executive action. Current President Donald Trump’s action put a sunset on the program in September 2017. Now, hundreds of thousands of young immigrants — who arrived in the U.S. without documentation as children — are living in fear as the deadline for Congress to make a determination approaches.

“What we saw when the DACA decision came out was a great deal of fear,” said Tim Faltyn, president of Oklahoma Panhandle State University, which he said boasts the largest percentage of Hispanic students in the state. “When DACA hit in September, roughly 30 percent of those (Hispanic) students left. Just disappeared. It was all fear-based because they were afraid that if somehow their financial aid papers would be tracked, then ultimately their parents or grandparents would get in trouble or be deported.”

Faltyn said his university had made a business decision to recruit Hispanic students for a variety of reasons, but uncertainty over DACA immigration status disrupted that effort.

“Typically, most human beings regardless of where you’re from, when you don’t have all the facts, you tend to fill in the rest of the story with stuff that isn’t even close to reality,” Faltyn said. “That’s what happened with us. We were up to about a 30 percent Hispanic student base, and now we’re back down to 25 percent.”

‘Uncertainty from D.C. is not a good thing’

After Wednesday’s event, which was hosted by a national organization called New American Economy and the local grassroots effort Immigration Coalition of Oklahoma, U.S. Sen. Jim Inhofe’s state director — Brian Hackler — offered empathy for those waiting on Congress to act on DACA and other immigration issues.

“Uncertainty from D.C. is not a good thing. I get it that this is really personal. I hope that’s not missed by anybody as this plays out,” Hackler said. “Uncertainty creates fear. Whether you’re an oil and gas company trying to sort through the uncertainty of the regulatory environment. Whether you’re in the press industry trying to figure out where that industry is going. Or if you are one of these Dreamers, trying to figure out what policy is going to look like in March or five years from now. It creates uncertainty. I understand that, and I believe the fear is real. Putting policies in place that don’t get us here again is important, and giving people certainty about what the future looks like is important.”

DACA recipients are often referred to as “Dreamers,” a reference to a 2007 failed attempt by Congress to address immigration status problems.

“Most DACA recipients are younger. Most of them are college educated,” said Julia Adame, a branch manager for Alterra Home Loans. “So, for home-buying opportunities, that is huge. If you are college educated, that means you have higher income potential than most people. For us, the DACA recipient is a great person to become a homeowner.”

Adame was one of several people who argued that DACA immigrants — whose last chance to extend their deadlines will be March 5, short of congressional action — boost the economy.

“From a Dreamer’s perspective, the fear is unbelievable among the Hispanic community in Stillwater and Tulsa where I live,” said OSU business management professor Chalmer Labig. “Let me give you an example of one very bright person that it would be such a crime for our country to let her go.

“She graduated from Northeastern State University, and she’s very good friends with some of my former students at Oklahoma State. She did not get to medical school — I mean, she got accepted — but she didn’t enroll, and she’s working as a scribe at one of the major hospitals in Tulsa. But she’s on hold because of the current situation, and it’s not like Oklahoma doesn’t need multi-lingual physicians. This young woman is so capable.”

‘Education is the great equalizer’

Like Labig, others spoke of immigrants whose stories often go untold.

“I probably have filed over 400 DACA applications,” said Kelli Stump, an immigration attorney. “Those were valid initially for two years, and you can extend them two years at a time. I’ve been able to convert DACA in some instances to permanent residency – some of my DACA clients who married U.S. citizens.”

Stump noted that anyone who entered the U.S. illegally — like most DACA recipients — must leave the country to re-enter legally, but a 10-year prohibition exists that discourages doing so.

University president Faltyn noted the value of allowing immigrant students to pursue an education easily.

“I am completely confident that if we can get these students in the educational pipeline, we won’t just change the trajectory of the student who graduates as a first-generation, their children will go to college, their grandchildren will go to college,” Faltyn said. “We are changing the trajectory of these families in ways I think you can’t even quantify.”

Myron Pope, vice president for student affairs with the University of Central Oklahoma, agreed with Faltyn.

“We’ve seen a very large increase in Hispanic students,” Pope said. “I’m a firm believer that education is the great equalizer.”

Pope said UCO had partnered with the Greater OKC Hispanic Chamber of Commerce to host community meetings with young Hispanics considering college. He said Trump’s DACA decision and the resulting uncertainty of what Congress will do, however, changed the success of those events.

“Just because of fear, the numbers plummeted,” Pope said.

Faltyn said it’s often the third generation of immigrants that begins to pursue higher education at greater rates, noting that a study commissioned by his university showed that many first-generation immigrants worked in agriculture or food processing, with second-generation immigrants starting small businesses.

“It’s that third generation that is now interested in going to college, and they’re looking at things like bachelor’s degrees and master’s degrees in business administration, animal science, those sorts of things,” Faltyn said.

‘We expect there will be some sort of bill’

When it was his turn to talk at the meeting, Hackler said he appreciated hearing the stories told Wednesday.

“This is really informative,” he said. “To be honest, the issue hasn’t been brought to us in this realm. It’s not going in one ear and out the other.”

Hackler said people hoping for a congressional solution this month should push their expectations to the spring.

“We expect there will be some sort of bill,” Hackler said. “It’s becoming more and more politically possible to get something done.”