How many Oklahoma high school athletes sustain concussions each year? Although more attention is being paid to the dangers of head injuries than ever before, the quasi-government entity tasked with overseeing high school athletics has no idea.

Despite posting a 2014 recommendation online under its “concussion guide” that it develop a reporting and tracking system for student athletes who sustain concussions, the Oklahoma Secondary School Activities Association collects no data related to head injuries.

“We’ve got some [schools] who have medical staffs who could provide that information. We’ve got some who don’t. So collecting the data could paint a misleading picture, we think,” said David Jackson, OSSAA executive director. “Data would be great, but having absolute accurate data would be important, and it’s hard for us to obtain that right now.”

Former players, physicians and state lawmakers have told NonDoc they are concerned by Oklahoma’s lack of data when it comes to athletic head injuries. Their comments were made before and after two Oklahoma youth football players — one 16 and one 14 — died on the football field from apparent brain injuries less than two weeks apart in September.

House Majority Leader Jon Echols (R-OKC) directly criticized the OSSAA for not following the recommendation that Oklahoma high school concussion data be collected.

“OSSAA is willfully failing our children in this regard, and their continued lack of even minimal efforts is something parents should be disgusted with,” Echols said.

Rep. Mickey Dollens (D-OKC), a Bartlesville graduate who played football at Southern Methodist University, said he also believes Oklahoma high school concussion data should be collected.

“To record and have data — and not just from football, but from all sports — to look at those athletes who are concussed and have a trail on that is common sense,” Dollens said. “How are you going to test the merits of [prevention or treatment] ideas if you don’t have data or information to look back on and see if what you are trying or implementing is, in fact, working?”

For its part, the OSSAA says it has ramped up efforts to educate coaches and parents about traumatic brain injuries, as well as the danger of repeated subconcusive brain blows in sports like soccer and football. Full-contact practice times have been dramatically limited in football, and all coaches take annual online trainings to learn about head injuries.

But OSSAA officials say collecting accurate data on head injuries would only be possible if every Oklahoma school had an athletic trainer.

“It is honestly a matter of funding,” said Amy Cassell, assistant director for OSSAA. “When you have to choose between teaching English or having an athletic trainer, that decision is pretty simple for you as an administrator, I would think.”

Echols called such an argument “ridiculous.”

“My two sons play high school football, and I have coached high school football. I love this sport, and I want to see it made safer. And the response by OSSAA angers and disgusts me,” Echols said. “A simple letter — which they could have written at any time, including today — that says, ‘Please self-report concussions you know of by sport,’ would have cost no money. If done [earlier], such a letter would have yielded at a bare minimum far more data than they have now.”

Jackson, on the other hand, said OSSAA is watching the Texas University Interscholastic League, which launched a mandatory reporting and tracking program for concussions in its 6A football division this year.

“Finding a way to get consistent data is one of their concerns, but they think it’s worth a shot to do it,” Jackson said. “We are going to wait and see what they do to determine whether that was good, useful data that they get from their 6A schools. Hopefully if it is we can do something similar, and I think maybe other states can follow suit.”

‘We can fix knees, but we can’t repair a brain’

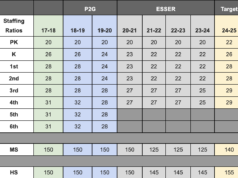

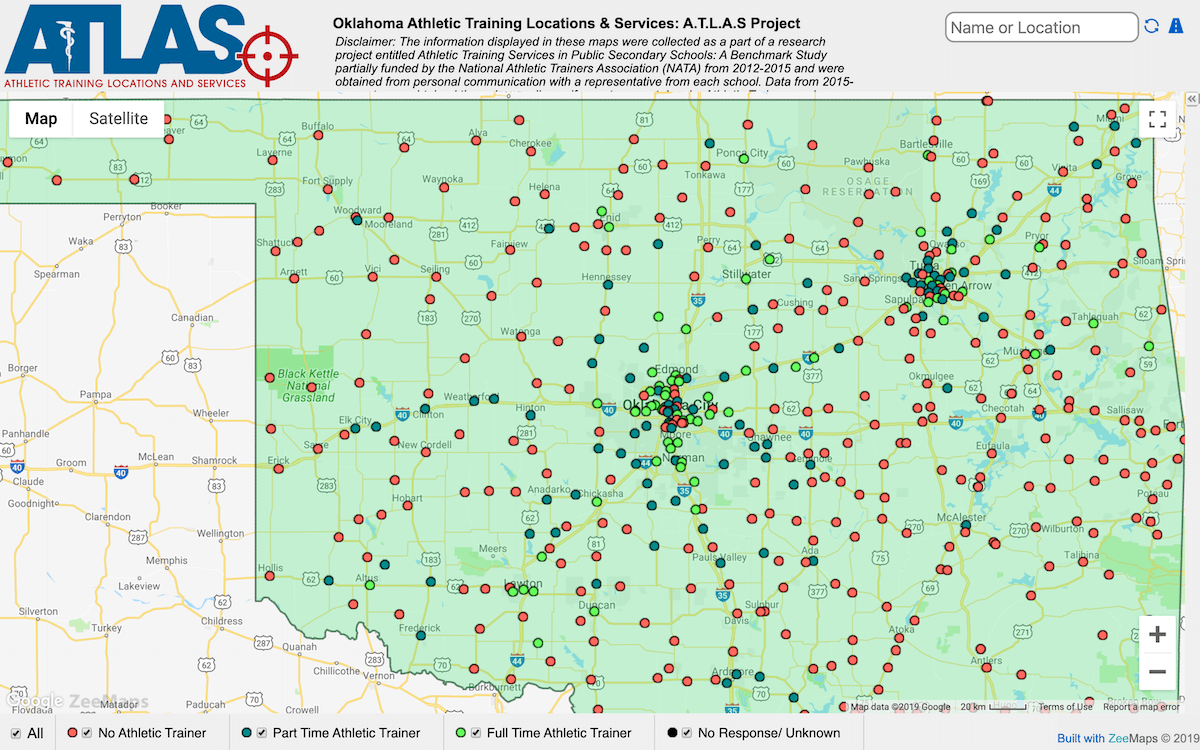

In Oklahoma, only about 32 percent of high schools have at least a part-time athletic trainer, something Joe Waldron, chairman for the secondary schools committee of the Oklahoma Athletic Trainers’ Association, calls a problem.

“That’s not very many, and that’s something that we hope to change,” Waldron said. “But when you talk about mandates, it doesn’t do us any good to have unfunded mandates. How can you ask someone to let a teacher go but you’ve got to employ an athletic trainer?”

Of 493 Oklahoma high schools listed on the National Athletic Trainers’ Association ATLAS system, only 65 (13.2 percent) are denoted as having a full-time athletic trainer. Another 93 (18.7 percent) are said to have a part-time trainer, while 335 (68 percent) are listed as not having an athletic trainer at all. While ATLAS notes a disclaimer about the origin of its trainer data, the numbers offer an idea of the resource gap between larger and smaller high school athletic programs.

“I would love to have one in every school,” Waldron said. “The main thing is trying to educate the public about what an athletic trainer does.”

Waldron spent 13 years of his 24-year athletic-trainer career at Heritage Hall and knows that a trainer’s role extends far beyond taping ankles and emphasizing hydration. In terms of head injuries, trainers preach awareness to coaches, players and families. They also look for symptoms during competition and help manage the “return-to-learn” and “return-to-play” protocols for students who have sustained a traumatic brain injury.

“The one thing that I always tell [players and parents] is we can fix ankles, we can fix knees, but we can’t repair a brain. So we don’t mess around and take chances with that. We are going to err on the side of caution,” Waldron said. “There is no game out there that is worth the risk of a kid having long-ranging effects or even death.”

When it comes to concussion data, Waldron said the OATA does “some reporting on injuries” to the national association and said he would look to see if he could find any data about head injuries in Oklahoma. He did not respond to a follow-up message seeking statistics.

“It’s an arduous process trying to get that information collected from across the state. (…) We don’t have personnel in every school that can track those numbers the proper way,” Waldron said. “In Texas, their schools Class 3A and above are required to have an athletic trainer on staff. Oklahoma is not there. It’s not a requirement.”

Echols, who said he sustained two concussions playing organized football and two concussions off the field, said OSSAA and OATA should try harder to find solutions.

“I certainly hope the coaches who deal with this decision wouldn’t accept those types of excuses from their players,” Echols said.

Neurologist: ‘This is kind of flying under the radar’

Without data, the scope of traumatic brain injuries among Oklahoma high school athletes is virtually unknown. Asked if they could estimate how many students are sustaining concussions each year in Oklahoma athletics, OSSAA leadership deferred to Waldron and the OATA.

“I don’t think from our office we are going to have anything like that,” said Cassel, the OSSAA assistant director.

On a national level, an estimated 1.6 to 3.8 million high school, college and professional athletes sustain sports-related concussions each year.

Such statistics — and lived experiences — underscore why state legislatures are looking at the issue. Between 2009 and 2015, all 50 states passed some sort of legislation on traumatic brain injuries. In Oklahoma, all high school coaches within OSSAA are now required to take an annual online training, and the Oklahoma Legislature wrote new statute making referees and coaches responsible for identifying head injuries:

If any game official or team official responsible for the care and safety of an athlete in an athletic event becomes aware or suspects an athlete is exhibiting signs, symptoms or behaviors consistent with having sustained a concussion or head injury, he or she shall remove the athlete from the practice or competition.

Title 70, Section 24-155 of state law goes on to stipulate that an athlete who has sustained a head injury must receive written clearance from a licensed health care provider to return to participation.

But no Oklahoma entity is mandated to receive reports on those concussions or to document that a written clearance was issued to resume participation.

Dr. Jaclyn Duvall, a Tulsa neurologist who specializes in the treatment of headache, said Oklahoma’s lack of data surprises her but is not unusual.

“I don’t think we know how many kids are really sustaining mild, moderate or severe traumatic brain injuries. I think this is kind of flying under the radar,” Duvall said. “I will tell you that the paucity of research surrounding concussion and the appropriate treatment is limited when we compare it to other sectors that have such an impactful outcome on young adults. We don’t have a lot. We don’t have a lot of postmortem research.”

Rep. Trish Ranson (D-Stillwater) is conducting a legislative interim study Thursday, Oct. 31, on traumatic brain injuries. She said the study will mostly center around her HB 1979, which would have created a TBI task force but was vetoed by Gov. Kevin Stitt.

Ranson said the fact no data is being collected does not surprise her, and she said she hopes her interim study can help bring that and other TBI issues to light.

“Unfortunately, we still lack data on the size of the issue, and tracking side effects of traumatic brain injury extends past high school,” Ranson said. “I believe OSSAA can play a part in the overall picture, but an overseeing entity needs to be established, as well as a funding source.”

Similarly, Oklahoma Watch is hosting a public forum on the risk of injury in high school sports scheduled for 6 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 22, at the Oklahoma History Center, 800 Nazih Zuhdi Drive. Cassell of the OSSAA is scheduled to answer questions, as is the president of the OATA and the president of the Oklahoma Parent Teachers Association.

Cassell: Education ‘more important’ than Oklahoma high school concussion data

In the meantime, OSSAA leaders say they are focused on educating players, parents and coaches about the risks of head injury, including the potentially deadly second-impact syndrome where someone whose brain has not recovered from a recent concussion absorbs another blow.

“I think the awareness probably reached a height at the NFL level in terms of head injuries when they started studying the brains of some NFL players who had died at a relatively early age,” said Jackson, who started at the OSSAA in 1996 and was named director in 2016.

The OSSAA’s sports medicine committee formed in 2007, which assistant director Cassell now helps lead. While football receives much of the attention surrounding head injuries, she noted that all OSSAA-sanctioned coaches must take annual online training and remain vigilant about concussion management.

“Soccer and cheer are the other two sports at the top of the list,” Cassell said. “In soccer, it’s primarily the headers. Not only are you hitting the ball with your head, you’re going up with your head at the same time as your opponent. A lot of noggins are hit.”

RELATED

Revisiting the science of sports-related concussions by Dr. Ashiq Zaman

Anecdotally, Cassell said OSSAA is hearing of fewer concussions in cheerleading owing to heightened awareness and prevention efforts.

“I think the more important piece of this is being able to educate people to recognize that some type of trauma may have occurred, remove that student from the situation and then monitor that situation to return to the field and return to the classroom in the appropriate manner by following certain protocols and certain steps,” Cassell said. “That, to me, is much more important than knowing how many there are.”

Until funding can be identified to help collect Oklahoma high school concussion data, Waldron said awareness is where the state can “improve on what we are doing.”

“The main thing is trying to get the public educated about injuries. We’ve done that with the coaches, but I think we have to educate the parents and the athletes,” Waldron said. “I think people get the idea that if they see something on TV it’s enough information. But it’s truly not, because there is so much more out there that they need to learn, especially about concussions.”

(Editor’s note: This piece is part of a series on concussions in Oklahoma amateur athletics. Read Matt Patterson’s Oct. 14 story The hazy, frightening world of a sports concussion to learn what it’s like having a concussion.)

(Correction: This story was updated at 3:20 p.m. Wednesday, Oct. 16, to clarify origins of a 2014 recommendation to track concussions listed on the OSSAA’s website.)

More #concussion coverage

The hazy, frightening world of a sports concussion