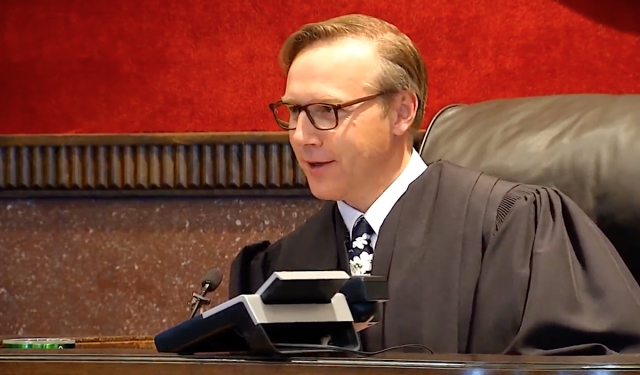

Cleveland County District Judge Thad Balkman stuck to his guns today in Oklahoma’s landmark opioid trial. The final judgment, released after an October summary order hearing, directs Johnson & Johnson and subsidiaries to pay more than $465 million for a one-year plan to abate Oklahoma’s opioid nuisance. (Balkman previously admitted a $107 million calculation error, dropping the $572 million figure in his August ruling to $465 million.)

While $465 million is a lot of money, Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter had asked for more than $17 billion to combat the nuisance over a period of at least 20 years. With only a one-year abatement plan ordered by Balkman, state lawmakers, attorneys and public health experts seem to have more questions than answers about what comes next.

“It just appears that there are a lot of unknowns here,” said Rep. Mark McBride (R-Moore) who attended several days of the opioid trial. “What happens 12 months from now?”

In October, Hunter and his contracted counsel argued that since Balkman accepted the state’s contention that a nuisance exists he should have listened to the state’s experts who said it would take at least 20 years to address.

“Once you find under equity that a nuisance exists and can be abated, it is the court’s job to remove it,” said Brad Beckworth, a Texas attorney contracted by Hunter. “If you believe it to be a menace and a nuisance that needs to be abated, we cannot stop short. We can’t do it, and I don’t think you can do it, with all due respect.”

Ultimately, Balkman did do it, repeating today in his final judgement (embedded below) what he wrote in his August ruling.

“Though several of the state’s witnesses testified that the plan will take at least 20 years to work, the state did not present sufficient evidence of the amount of time and costs necessary, beyond year one, to abate the opioid crisis,” Balkman wrote.

The judge also wrote that the state’s contracted attorney fees shall be paid in accordance with their agreements and that “the court retains jurisdiction for purposes of administering the abatement plan and the associated abatement plan funds as ordered herein.”

“Otherwise, this matter is concluded,” Balkman wrote.

Appeal expected

“Concluded” can be a tricky word. Attorneys for Johnson & Johnson told NPR on Friday that they plan to appeal Balkman’s ruling. During the October summary order hearing, they argued his nuisance finding was unconstitutional, and they also sought a settlement credit based upon Oklahoma’s settlements with other opioid producers.

They did not receive one Friday.

“Under Oklahoma law, defendants are not entitled to a settlement credit to account for the settlements entered between the state and the former defendants who settled and were dismissed, because there has been no finding of fault entered against any other potential tortfeasor, nor was any such finding requested by defendants before or during trial,” Balkman wrote.

While Johnson & Johnson may appeal the final judgment, other Oklahoma leaders may be inclined to do so as well. Balkman’s limitation of the abatement plan funding to only one year could leave the Oklahoma Legislature with more than $400 million in annual obligations, unless the abatement procedures — including patient screening, employee training, student education and new agency hires — are quickly terminated after 12 months.

Gov. Kevin Stitt and legislative leaders filed an amicus brief in October that supported Hunter’s argument that more than one year’s worth of funding was needed to abate the opioid nuisance. The brief was opposed by Johnson & Johnson. Still, the amicus brief contended that, since Balkman found a nuisance, it became his responsibility to direct a successful abatement plan instead of obligating taxpayers.

In the end, Balkman disagreed.

Regardless, his declaration that opioid manufacturers had used misleading and false marketing strategies to create a nuisance — a fundamentally different finding than the recovery of damages — stands as a bold legal opinion with potential impacts down the road.

“As a matter of law, I find that defendants’ actions caused harm and those harms are the kinds recognized by 50 O.S. Section 1 because those actions annoyed, injured and endangered the comfort, repose, health and safety of Oklahomans,” Balkman wrote. “Defendants also pervasively promoted the use of opioids generally. This ‘unbranded’ marketing included things like print materials that misleadingly touted the safety and efficacy of opioids as a class of pain medication, as well as online materials that promoted opioids generally.”

Hunter’s team offered a brief statement on Friday’s final judgment.

“It’s a lengthy document. We are thoughtfully and thoroughly reviewing it and will respond in a timely manner,” said Alex Gerszewski, Hunter’s communications director. “We will be providing a formal response in the next few days.”

Background on Oklahoma’s opioid trial

Hunter filed suit against Johnson & Johnson, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Purdue Pharma and various subsidiaries in June 2017. Hunter announced a settlement with Purdue in March 2019 and second settlement with Teva in June 2019, almost a month after Balkman began a non-jury trial for the case.

The Purdue settlement in particular alarmed state lawmakers, as it allocated Purdue’s money to a yet-to-be-formed nonprofit foundation in support of the Center for Wellness and Recovery at the Oklahoma State University Health Sciences Center, an effort Hunter had personally championed in the past.

The Teva settlement also concerned legislative leaders, who had passed new law emphasizing the attorney general’s responsibility to deposit lawsuit proceeds into the state treasury. Hunter and his contracted counsel attempted to circumvent that law, arguing the court should retain the Teva settlement until the Johnson & Johnson verdict was announced. Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt and the two leaders of the Oklahoma Legislature filed a brief challenging that assertion.

Read Judge Balkman’s final judgement

Loading...

Loading...

(Correction: This story was updated at 4:20 p.m. Friday, Nov. 15, to correct reference to which party opposed an amicus brief. NonDoc regrets the error.)