In the early spring of 2018, former Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Joe Byrd found a seat on the airport shuttle headed to Tulsa International Airport and heard over the radio a familiar, yet surprising sound: the Cherokee Youth Choir singing in his endangered native tongue.

“Who would ever imagine 20 years ago that we would be hearing our own language in a shuttle bus away from our rural areas?” asked Byrd, a current Tribal Council member who is fluent in the Cherokee language. “I couldn’t help but swell with pride and realize the distance we have come.”

This story was reported by Gaylord News, a Washington reporting project of the Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Oklahoma. This series entitled Exiled to Indian Country details the stories of how each of Oklahoma’s 39 tribes ended up in the state.

The Cherokee Nation holds onto a crucial piece of tribal culture through its remaining 2,000 native speakers, a majority of whom are age 50 and older. The youngest fluent Cherokee speaker is 35, meaning the language faces potential extinction when older members die.

“If you hear people speaking Cherokee, even if you don’t understand it, it reminds you that we’re a people that have existed since time immemorial (…) and that we’re distinct people,” said Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. “If that stops happening, then that distinction starts to melt away.”

According to the Cherokee Nation’s official website, the Cherokee Nation Language and Cultural Preservation Act was signed in 1991, which, in part, identifies the language as an important part of Cherokee identity and recognizes the need for its preservation.

The preservation of a culture

In an effort to promote and preserve the language, an immersion school called Tsalagi Tsunadeloquasdi was founded in 2001 in Tahlequah with 26 students and four staff members.

Today, Tsalagi Tsunadeloquasdi supports nearly 100 K-6 grade students and is the first Oklahoma public school for Cherokee language immersion. Students are taught using only the Cherokee language and syllabary.

“If we don’t [teach our language], then in a generation we will have gaming, we’ll have businesses, we’ll sell car tags, we’ll have a health care system, but we won’t have people speaking our language,” Hoskin said. “And if we don’t have people who speak our language, maybe we won’t have people who practice our culture and traditions, and maybe we’ll lose our history a bit, and what have we become? We’ll be a gaming corporation, a business portfolio and a health care delivery system, and maybe even lose our identity.”

The Cherokee syllabary traces back more than 180 years to the original homelands of the tribe before its forced removal on the Trail of Tears.

At the time of removal, the Cherokee Nation was well-established with a successful government, an agricultural economy, a tribal religion and spoken and written languages. The tribe had a 90 percent literacy rate, but by the time Oklahoma became a state in 1907, the literacy rate plummeted to 10 percent, Byrd said.

Sequoyah, a blacksmith, trader, silversmith and soldier in the War of 1812, introduced the official Cherokee syllabary in 1821 after years of development. The syllabary would be the foundation of the Cherokee’s resistance to removal.

“We did a couple things (to resist removal). We reorganized our government [with] a written constitution,” Hoskin said. “You can’t have a written constitution that your people understand unless there’s a written language. That’s the genius of Sequoyah’s syllabary.”

Hoskin said another way the Cherokees resisted removal was through the founding of the Cherokee Phoenix, the first Native American newspaper. Hoskin said the newspaper, which published in Cherokee and English, allowed the nation to inform the white settlers and Cherokee people of current events.

“If we hadn’t have done that, I think we would have been removed earlier,” Hoskin said. “And I think the removal would have been more devastating.”

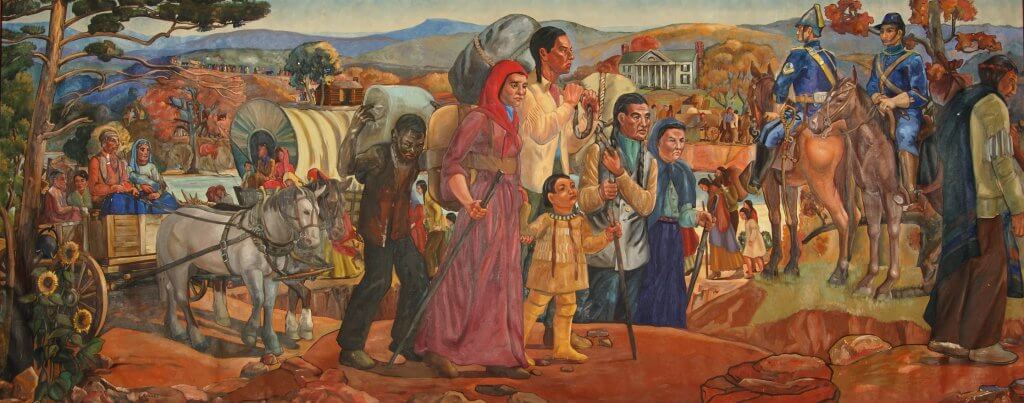

Removal began when the Treaty of New Echota was signed in December of 1835 by a handful of Cherokees who lacked authority to do so, said Jack Baker, former Tribal Council member, president of the Oklahoma Historical Society and national president of the Trail of Tears Association. The treaty gave the Cherokees a two-year period starting May 23, 1836, to leave their homelands in South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia and Alabama and move west of the Mississippi to present-day Oklahoma.

John Ross, the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1828 to 1866, and his Tribal Council fought to invalidate or renegotiate the treaty for the Cherokee people. However, the two-year period came to an end, and the U.S. military was sent to initiate forced removal.

Federal troops, with the aid of the Georgia National Guard, began rounding up the Cherokee people. They raided homes and forced families to leave their belongings, land and life as they knew it behind. The Cherokee people were then placed into 31 stockades and eventually into 11 camps in Alabama and Tennessee.

Winfield Scott, a military commander at the time, was in charge of the removal of the Cherokee Nation. The first three detachments of Cherokees began the journey to Oklahoma in June 1838.

By the time all 13 detachments arrived in Indian Territory in March 1839, a quarter of the Cherokee population had died along the way or in the stockades awaiting removal.

‘They’re survivors. They’re really survivors’

Even after the Trail of Tears, the unjust treatment of the Cherokee Nation was far from over. The nation’s once communal land was divided up into allotments and distributed to Cherokee citizens.

A few years after allotment, the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs placed restrictions on citizens who were half-blood or more. The allotments owned by these citizens could not be sold without consulting the federal agency, and if the land had oil or other valuable properties, a guardian would be assigned, Baker said.

“A lot of us (…) have more Indian in us than what’s on record,” said Colleen Dixon, an 87-year-old Cherokee Citizen. “I know my great-grandmother she (…) wouldn’t tell if [she] was over half.”

Dixon is a descendant of Nancy Ward, a Beloved Woman and political leader of the Cherokee nation.

Dixon said her mother was assigned a guardian after she was allotted land. Her guardian was a white man who owned a land company. He married Dixon’s mother when she came of age, then sold her land and divorced her.

Stories like hers were common during the years after the removal. But she said one thing has proven true throughout history.

“They’re survivors. They’re really survivors,” said Dixon. “And if you start at the beginning of their beginning and where they are now, it’s awesome. They just need a chance.”

‘A point of pride for the Cherokees’

Today, the Cherokee Nation stands as one of Oklahoma’s top economic contributors. According to the tribe’s website, Cherokee Nation Businesses contributed $2.16 billion to Oklahoma’s economy in fiscal year 2018.

Hoskin said he thinks it’s important for people to know the history of how Cherokees picked themselves “back up within a decade and rebuilt.”

RELATED

Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. talks business, language and Freedmen by Tres Savage

“We constituted our government again, took this political split of historic proportions, and we bound ourselves back together,” Hoskin said. “We took the resources we had left (…) and experienced a golden age so quickly after one of the most destructive things the United States has ever done to a people. I think that’s a point of pride for the Cherokees.”

Reflecting on how their ancestors fought for the Cherokee Nation inspires tribal citizens to keep fighting today, Byrd said.

“While [the Trail of Tears] was a tragic event and part of our history, it is not our defining moment,” Byrd said. “ We are here today, and it tells the world that the survival of our people has made us stronger and makes us continue to fight and to continue exerting our sovereignty of who we are.”