Jolene Oldenberg, principal of Mulhall-Orlando High School, often stays late at school answering emails and completing all her other online work. Many of these tasks could, theoretically, be done at home. But like many rural Oklahomans, Oldenberg does not have reliable internet access at her house, so she depends on the school’s internet connection.

“It’s just not an option out here right now. I spend long, long hours at the office and take care of a lot of stuff here” Oldenburg said in June.

Her situation is not unusual. For the students and staff of Mulhall-Orlando and the residents of many rural counties across the state, high-quality internet is still hard to get and expensive when it is available.

So when the COVID-19 pandemic hit and schools all over the country transitioned to online learning, Mulhall-Orlando had to come up with a low-tech alternative.

The school finished out the spring semester using a paper packet system. Each week, teachers would leave their lesson plans at school, and the plans were then taken to the Mulhall post office. The post office acted as a drop-off site, where parents or students would pick up new lessons and turn in completed ones. It was an innovative solution, but it wasn’t ideal.

“It takes out any type of direct instruction,” Oldenburg said. “There’s so many tools these days, Zoom and other internet platforms (…) that we are not able to use because of the lack of internet here. The quality of instruction was not near what it could have been (in the spring).”

At first glance, the lack of an internet connection might seem like just an inconvenience, but the COVID-19 pandemic has underlined how central reliable internet access has become to everyday life. It has also given new urgency to efforts to address the lack of connectivity, particularly in rural areas.

‘The internet is no longer a luxury’

Tyler Cooper is the editor-in-chief of BroadbandNow, a website focused on providing people in rural areas with information about what, if any, services are available in their area.

“The internet is no longer a luxury,” Cooper said in an interview with NonDoc. “It’s no longer something we just use to browse Netflix on or something like that. Our children increasingly rely on the internet to learn at home. Right now, we’re all sort of participating in this grand experiment, but the harsh reality is there are millions of Americans right now that are stuck in place and don’t have access to these essential services.”

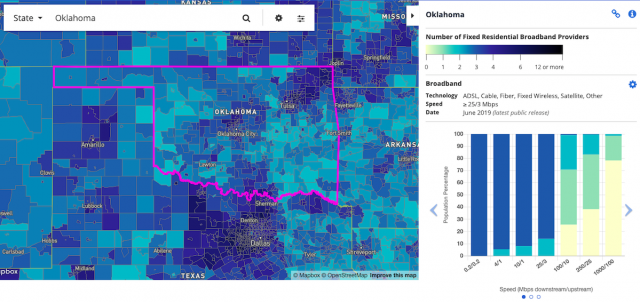

A report released earlier this year by the Federal Communications Commission estimated that approximately 5.6 percent of Americans don’t have broadband access. But in rural areas 22.3 percent lack access, and on tribal lands the number is 27.7 percent. Oklahoma ranks 26th in the nation in terms of broadband access, with 57.8 percent of Oklahomans living in areas with wired broadband service, according to BroadbandNow.

There are two big challenges facing rural America when it comes to internet access, according to Cooper.

The first is how the data used to determine who already has access are collected. At the national level, the government relies on companies to self-report which communities have service.

The problem is that companies report data at the census block level, not by individual houses or neighborhoods. If one house in the census block has broadband access, the entire section is marked as having service.

Cooper added that communities officially listed as having broadband access are often served by only one provider, which leads to the second challenge: In areas with only one provider, the lack of competition can lead to unaffordably high rates.

“You kind of have this double-edged sword,” he said. “In areas where you do have service, it’s unaffordable, and obviously in many areas in rural America, the technology itself just doesn’t even exist. The infrastructure is not in place to even take advantage of these services.”

‘As future-proof as anything out there’

There have recently been efforts at both the state and national levels to address this issue.

Earlier this year, the Oklahoma Legislature passed a bill to create a Rural Broadband Expansion Council, which is tasked with increasing access to broadband and collecting better data on which communities lack service.

In January, the FCC established the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund, which will spend $20.4 billion over 10 years to bring high-speed broadband to unserved areas. The FCC also administers the Connect America Fund, another initiative to increase broadband access, including in many Oklahoma communities.

When the internet does come to rural areas, it is installed by companies such as the Lake Region Electric Cooperative, which provides internet and telephone services to Cherokee and Wagoner County.

LREC has operated in Oklahoma since 1949, originally providing phone lines and electrification to underserved areas as part of the Rural Electrification Act during the Roosevelt administration. LREC is currently in the second phase of a three-part plan to extend broadband to the company’s coverage area. The first phase brought service to more parts of Cherokee County. The current phase is focused on Wagoner County and is scheduled to be completed by June 2021. The third phase will fill in any gaps left in the grid so that every member of Lake Region Electric Cooperative will have the option of home internet.

Glen Clark, LREC’s director of marketing and customer relations, said that even though the company had the advantage of existing infrastructure, installing broadband is costly.

“We had the infrastructure, and by that I mean the poles to hang the fiber on,” he said. “It’s still very, very expensive to run the fiber. Somebody just starting out would have to run the main distribution lines, but we had the infrastructure and we had the poles.”

There has been a surge in service requests since the beginning of the pandemic.

“We’ve almost been overwhelmed with sign-ups,” Clark said. “It’s challenging because we have the main line infrastructure in place, but not all of the drops are constructed, and that’s what it takes to go to the homes. We’re just running a hundred miles an hour to keep up with them.”

Clark compared the current expansion of broadband to the process of bringing electricity to the same areas of the state.

“You can still find folks out here in rural Cherokee County who remember the day the lights came on in the 40s and 50s,” he said. “The reason that these rural cooperatives even exist is because nobody would bring electricity to these rural communities. It wasn’t profitable, it just wouldn’t pay off.”

But, like electricity, internet access promises to be a vital resource for years to come.

“The good fiber-optic internet, we feel like it is as future-proof as anything out there,” Clark said. “The rural electrification of the 21st century was bringing fibre-optic internet to rural areas.”

Making do in the meantime

For now, though, Oldenburg and others have had to do what they can to make it through the pandemic. Mulhall-Orlando Public Schools moved to in-person classes in the fall, with masks and social-distancing and regular disinfecting. So far, they haven’t had any COVID-19 cases at the school. But if that changes, the district might be forced to return to the packet system, Oldenberg said.

Rural Broadband Expansion Council co-chairman Rep. Logan Phillips (R-Mounds) praised the innovation educators have exhibited during this time.

“Our education system is filled with very loving and creative people,” he said. “I’ve seen them create hotspots with buses and go out and open up the library system so students can come in and social distance but still access the internet. I’ve seen them open up the parking lots and throw wifi routers out there so students can come in their cars and sit there.”

But Phillips — whose district includes Hughes and Okfuskee Counties, where less than half of households have broadband access, according to BroadbandNow — also emphasized that the effects of poor internet reach much further than the relatively high-visibility area of education.

“My constituents without access, in the digital divide, aren’t doing Zoom calls with their family members,” he said. “They’re not able to do a virtual face-to-face call. They’re isolated. They’re lonely. They’re without resources.”

Phillips said he hopes that this difficult time will, however, spur change in the future.

“Moving forward, outside the pandemic, we have public spaces available,” he said. “There’s different technologies to help for those extremely outside of the district students. But nothing compares to actually putting line in the ground and bringing broadband to the district.”