SQ 805 will be on Oklahoma’s Nov. 3 ballot, but its proposal was originally developed in 2016 when a comprehensive, statewide task force assembled to identify prison reform initiatives that could dethrone Oklahoma as No. 1 in the world for incarceration rates.

The Pew Charitable Trust and The Crime and Justice Institute, national leaders in policy analysis and development, led the Oklahoma Justice Reinvestment Task Force. According to Pew, the purpose included producing data-driven recommendations “to protect public safety, hold offenders accountable, control costs, and reduce the population under correctional control.” The official report included 27 policy recommendations that would save $1.9 billion in prison costs and reduce the prison population.

Recommendation No. 11 advised Oklahoma lawmakers to revise sentence enhancements for nonviolent offenders.

Current sentence enhancements allow district attorneys to seek incarcerations longer than a charge’s maximum sentence if the citizen has received a prior felony conviction, regardless of its nature. The task force found that a person convicted of a nonviolent offense in Oklahoma can have a life sentence tacked onto a maximum penalty thanks to the use of sentence enhancements.

According to the report, longer prison sentences do not equate to better recidivism rates. However, Oklahoma imprisons nonviolent offenders for longer and at higher rates than neighboring states (48 percent higher than Missouri, for example, according to the official report).

Policy created to follow the task force’s advice and limit the use of sentence enhancements for non-violent offenders was introduced legislatively in 2017, 2018 and 2019 to no avail. After three attempts, the advocacy group Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform decided to move the policy to a vote of the people.

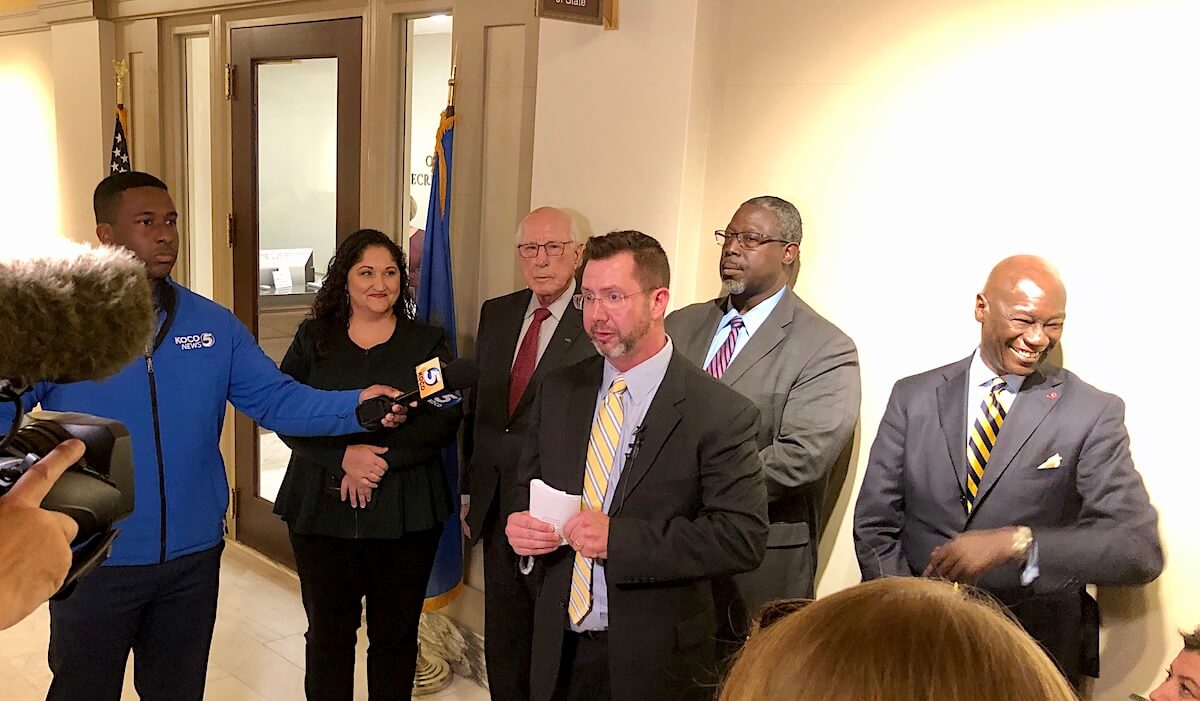

In order to do so, Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform had to collect 178,000 signatures of registered voters within 90 days of Dec. 25, 2019. The group ceased efforts to collect signatures 12 days shy of the deadline owing to COVID-19 concerns. Kris Steele, a former Republican member of the Oklahoma House of Representatives and speaker of the House, is the executive director of Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform.

“The response from voters was just overwhelming,” Steele said. “We turned in well over 250,00 signatures from voters who say that they want to see this kind of change occur.”

Reaching all requirements, SQ 805 prepared to face the ballot.

Current debate

Steele said SQ 805 gives Oklahoma an opportunity to model prison reforms that have been successful in other states and to rebuild communities pulled apart by long prison sentences.

“Oklahoma prisons are overcrowded, and currently we hand down some of the longest prison sentences in the country,” Steele said. “The biggest reason for that is the use of these sentence enhancements that can add decades to a person’s sentence, and it’s costing Oklahomans a fortune.”

Opponents of SQ 805, however, say it would enshrine this restriction in the Oklahoma Constitution and would lock in the definition of “violent felony” to be only as defined by Title 57, Section 571 of state statute as of Jan. 1, 2020.

Those opponents include Gov. Kevin Stitt.

“In SQ 805, the 10th DUI and the first DUI have to be treated exactly the same,” Stitt said.

Under SQ 805, people who are convicted of a nonviolent crime could still be sentenced to prison up to the maximum time allowable for that offense, but they would not receive additional time in prison beyond the maximum range of punishment because of prior convictions.

“There’s simply no evidence that these excessive, harsh sentences for non-violent offenses do anything in the way of reducing crime or increasing public safety,” Steele said. “As a matter of fact, the research is conclusive that it tends to make the situation worse, and it costs the taxpayers of Oklahoma a whole lot of money.

“There’s no way that you can convince me — as a lifelong Oklahoman — that the people of Oklahoma are more criminogenic than anywhere else in the nation.”

According to the Oklahoma Council of Public Affairs, SQ 805 should save Oklahoma taxpayers upward of $186 million dollars and “reduce Oklahoma’s prison population by 8.5 percent over the next 10 years.”

But Angela Marsee, a district attorney covering five counties in western Oklahoma, said she is concerned about the constitutional nature of SQ 805 and what that could mean for potential unintended problems.

“Even though there may be a recognition that problems exist with State Question 805, the only way to fix it is by another constitutional vote,” Marsee said.

Stitt expressed similar concerns.

“To put sentencing reform inside our constitution is the wrong way to do that,” Stitt said. “It basically ties the hands of our prosecutors and district attorneys.”

The Yes on 805 campaign, however, recently announced endorsements from more than 100 Oklahomans and organizations, including former District Attorney Kalyn Free. Free told the story of an Oklahoma woman who served 17 years for a drug crime. Free said the woman’s sentence did not serve the state of Oklahoma or her children well.

“She never should have been in prison that long,” Free said. “That is a broken system. It cost her family, and it cost society.”

A person convicted of a repeat, nonviolent drug offense tends to spend substantially longer in Oklahoma prisons than similar people do in any other state, according to Steele.

“There are still consequences in place under 805 for people who break the law, but it’s a matter of appropriate consequences,” Steele said. “(SQ 805) takes a step forward in reducing some of the disparities that exist within our criminal justice system.”

Marsee said she will vote “no” on SQ 805 in part because it “limits the definition of a violent offense to our statutory definition which existed on Jan. 1 of 2020.”

“There are still a lot of crimes that are very serious,” Marsee said. “While they may not be statutorily ‘violent,’ they are certainly in reality violent, such as domestic violence, crime and animal abuse.”

Violent felony offenses are defined in Section 571 of Title 57 of state statutes and include crimes such as murder, child abuse, rape and robbery. Non-violent crimes are crimes that do not involve force or injury to another person and are not listed as any of the 52 crimes listed in section 571 of Title 57.

Concerning domestic violence, not all acts are listed as violent. In May, Governor Stitt signed a bill making specific acts of domestic violence a violent crime, such as domestic abuse by strangulation and domestic abuse with a dangerous weapon.

“The majority of prosecutors believe in this system that’s based entirely on punishment and retribution,” Steele said. “They’re unable to see the value in investing in treatment and alternatives to long incarceration.”