Oklahoma City’s northeast side is one of many food deserts in the Sooner State. However, as residents from the 73111 ZIP code achieve objectives to buffer the situation, the same tactics could be used around the state.

With the loss of its only major grocery store last year, residents of northeast OKC have had to find other food options — many unhealthy — from nearby convenience stores. Some who can afford it have others drive them to full-sized grocery stores miles away.

“Lots of us don’t have cars or money to pay people to take us to stores,” said Pamala Walters, a 66-year-old resident.

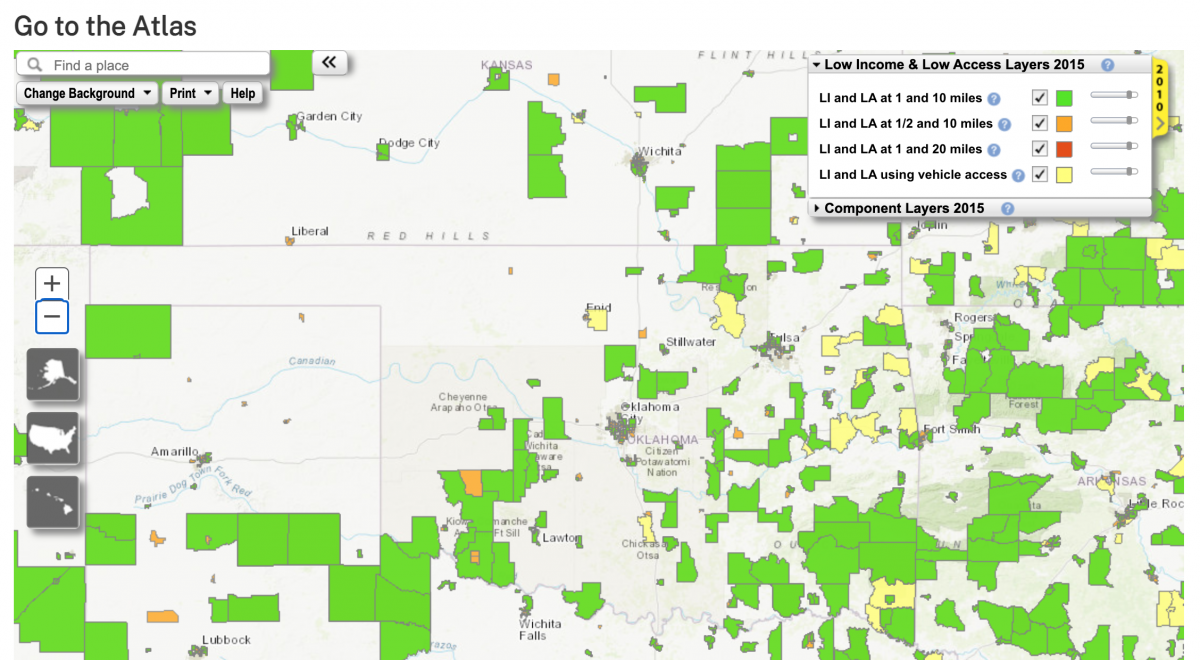

Food insecurity is a primary social issue in northeast OKC, but it is not unique to the state’s largest city. As of this year, 15.6 percent of Oklahoma households deal with food insecurity, a statistic that places Oklahoma 46th in the nation for food security. Similarly, 14.8 percent of Oklahoma households live in poverty.

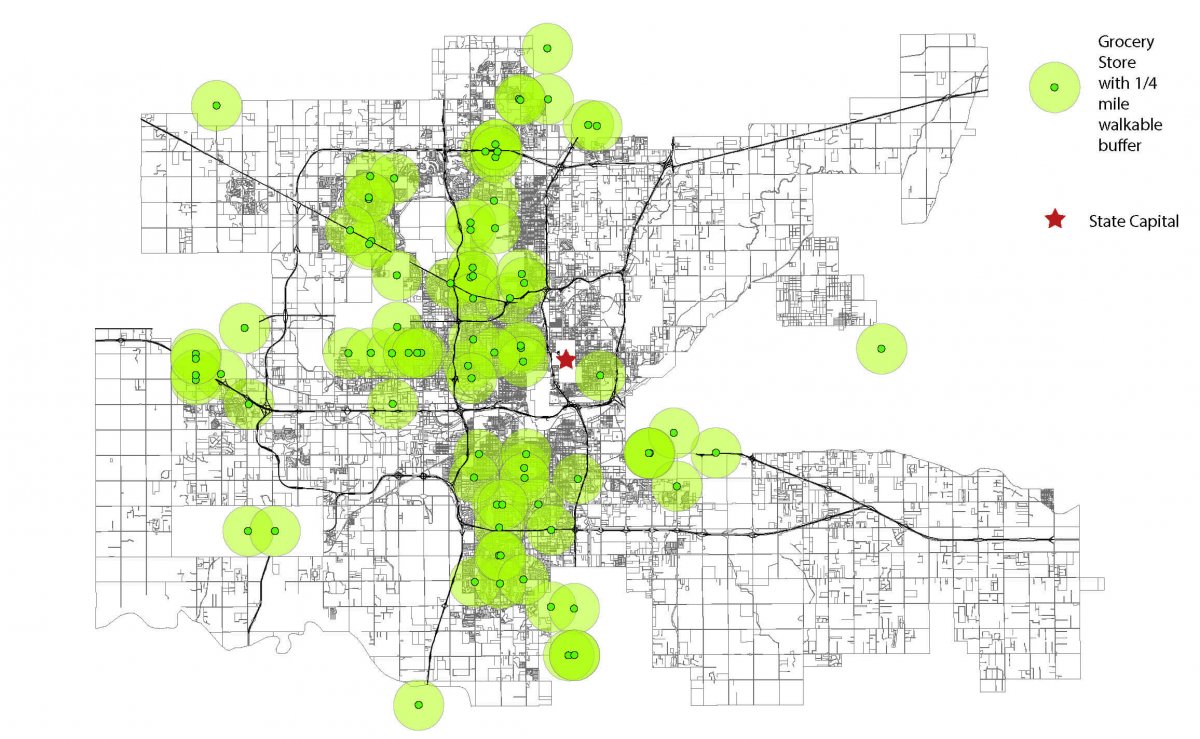

Healthy food options are limited in northeast OKC, however, a Homeland is being built at the corner of Northeast 36th Street and North Lincoln Boulevard. That project comes in the wake of a promised Uptown Grocery development failing to come to fruition.

Having broken ground on Oct. 1, the new large Homeland grocery store is scheduled to open by the fall of 2021. The store will be the company’s first built from the ground up in decades, and while it will end the area’s food desert designation, transportation from farther-east neighborhoods will remain a concern.

Meanwhile, as families wait for the new full-sized grocery store’s opening next year, northeast OKC residents still have challenges to face. Some stopgap solutions currently in play could sequester some of the effects of the food desert on residents’ health, highlighting possible options for the rest of the state.

‘Life just seems better’ with access to quality food

A food desert is defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as a census tract area that meets one of three criteria:

- a poverty rate of at least 20 percent;

- in urban areas, a median family income not exceeding 80 percent of the statewide median family income or 80 percent of the metropolitan area;

- in non-urban areas, a median family income not exceeding 80 percent of the statewide median family income.

But there are other specific criteria an area must meet. In urban areas, the USDA says at least 500 people (or 33 percent of the population) must live more than one mile from the nearest large grocery store. For rural areas, at least 500 people (or 33 percent of the population) must live more than 10 miles from the nearest large grocery store.

Bryce Lowery, an associate professor of regional and city planning at the University of Oklahoma Christopher C. Gibbs College of Architecture, said he has heard about the state’s explosive rates of obesity and diabetes, particularly among those in poverty, people of color and tribal communities.

“We see that if you’re well off and white and have access to good food, your life just seems to be better, and there’s a lot of it here in Oklahoma,” Lowery said. “That really struck me.”

The 73111 ZIP code in northeast Oklahoma City has a population of 11,781 — where 83.2 percent of residents are Black — and a median household income of $22,185. The area’s Census tracts have also been a food desert since 2019 after the unexpected closure of it’s only large grocery store at Northeast 23rd Street and Martin Luther King Boulevard.

Lowery teaches courses in geographic information systems, food systems, neighborhood planning and urban design. He also researches environmental and socioeconomic influences of neighborhood well-being, as well as land use policies that aim to improve community health.

He said he has been to every grocery store in the state.

“I started looking at grocery stores and have been studying grocery stores for a while thinking about how we either help communities get grocery stores — which is a really complicated process and it usually involves financial incentives — or thinking about alternatives to grocery stores,” Lowery said.

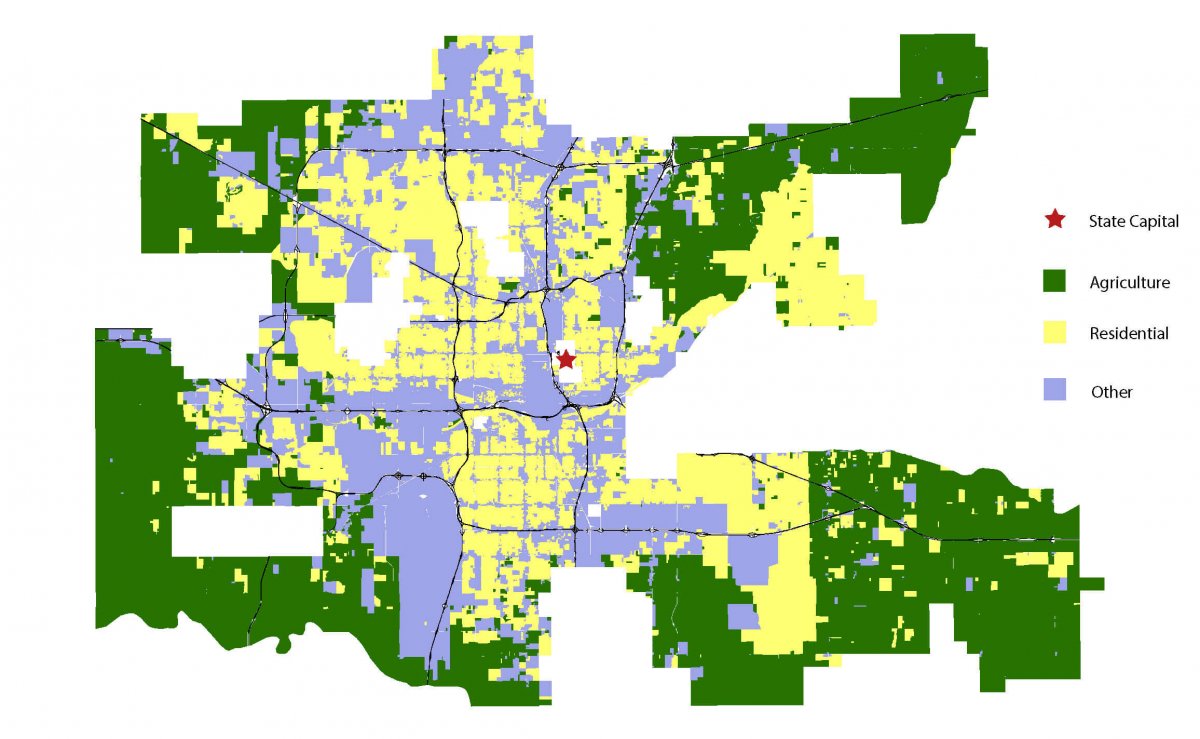

Lowery is a Californian who came to Oklahoma in 2014. When he moved here, he was surprised at the state’s agricultural land.

“I didn’t really realize this when I moved here, but we really don’t grow any food in Oklahoma — not to a large enough extent to where it creates a big economy,” he said.

Lowery said Oklahoma is a ranching state — mostly cattle — but needs to think about ways to grow food in an environment and climate that is tough in the first place. While Oklahoma City has a lot of unutilized land, he said there are opportunities from a planning perspective, such as empty lots or industrial spaces that are no longer in commission.

“What we want to say is, ‘We need fresh fruits and vegetables,’” Lowery said.

A June 2017 overview on food deserts in Oklahoma by the Regional Food Bank of Oklahoma reported that out of the state’s 77 counties, 54 contain food deserts.

Out of the 77 counties, 76 contain areas of low access to large grocery stores. Of those 76 counties, 45 of them have 50 percent or more of their population living in areas with low access to large grocery stores. Harmon County is the only county without an area designated as “low access” to large grocery stores.

Advantages taken on open land in northeast OKC

Some residents in the northeast OKC food desert have been able to obtain produce from community gardens and small neighborhood markets along Northeast 23rd Street.

One organization that took advantage of five available acres in the 73111 ZIP code is Restore OKC.

Ann Coulter, Restore OKC farm director, said the organization has a community garden space that is free to the public. She said her organization grows a variety of produce from March through October, such as tomatoes, collard greens and peas.

While their first priority is to employ seventh through 12th-grade students as interns on their farms so that they gain agricultural experience, Restore OKC has turned one of their buildings into a neighborhood market. They will also be building a grocery store on Northeast 23rd Street.

Ernest Odunze, director of Restore OKC, said his organization aims to upgrade their neighborhood market into a farmer’s market by January.

“By spring of 2021, a majority of our produce will come from our vertical growing towers,” Odunze said. “We have 72 aqua tonic towers and a greenhouse. What we are hoping is that they will yield over 60,000 pounds of produce for the community.”

Coulter said three of their five acres have been developed where the community garden — soon to have an orchard — takes up about an acre. Their production space, which Coulter said features the greenhouse that measures about 3,000 square feet, takes up the other two.

There, she said the greenhouse, which has three bays, is used to grow different greens and herbs. Coulter also said their team will do more research on what else they can grow indoors.

“The size of an average greenhouse, we have three of those,” Coulter said.

Coulter said two of the acres will be dedicated to have more animals. Currently, Restore OKC has 50 chickens providing about 12 dozen eggs each day for the market.

‘Oklahoma is built for the automobile’

Organizations such as Restore OKC have made it easier for some residents to find healthier food options as an alternative to buying fast food or shopping at gas stations.

Walters, the 66-year-old resident of northeast OKC, is retired and lives near the Restore OKC farm. She said she shops from their market at least twice a week.

“This area has a high rate of senior citizens,” Walters said. “That’s another reason why I’m glad to have (Restore OKC) — it’s convenient for them.”

At one time, Walters owned her own vehicle, but she said when she lost it, things became more difficult for her. She lives with her 45-year-old son and 9-year-old great grandson. She used to have to get a ride with her friend to the Crest Foods off North Douglas Boulevard and Reno Avenue, nearly eight miles away.

Lowery said people in general have to go a long way for grocery stores. Living in a food desert makes everything harder.

“Oklahoma is built for the automobile. We don’t have a lot of walkable communities or bicycle access yet. It’s getting better,” he said. “We have a long way to go to really help people get to food through multiple different ways. People here need a car.”

Walters explained what it is like to be one of those people.

“If you had the money [you could get] people to take you somewhere,” she said. “It would always be that difficult because people don’t offer to help one another. I don’t want to say everybody’s like that, but nowadays if you have someone even offer to take you, you’d have to buy them gas and all of that.”