When several state agencies moved from their more antiquated office buildings to the former Sandridge Energy complex, at 123 Robert S. Kerr Ave., in Oklahoma City, last year, the relocation was meant to provide the agencies’ employees with an improved workspace.

Some state employees with disabilities, however, say they have faced problems with accessibility at their new offices in the downtown-OKC building, particularly when it comes to parking, and that the agencies they work for have been reluctant to make changes.

“I think they’re just putting their hands up saying, ‘Well, it’s not our fault that you’re handicapped,” said Jeffrey Henderson, an employee of the Oklahoma Tax Commission.

An assessment by the state’s Office of Disability Concerns completed in December found that the building, now called the Oklahoma Commons, did not meet certain requirements for accessibility set out in the Americans with Disabilities Act, both for employees who work in the building and for members of the public who might need to visit one of the agencies housed there.

The assessment, which was limited to parking garages and the lobby areas of the building, mentions issues such as narrow elevators, doors that would be difficult for wheelchair users to navigate, an insufficient number of handicapped parking spaces and an employee parking garage that did not provide an “accessible route” as required by the ADA.

Though some changes, such as the installation of automatic door openers, have been made following the assessment, employees who have complained to the Office of Disability Concerns are especially upset about the parking situation, which has not changed.

Doug MacMillan, the director of the Office of Disability Concerns, who completed the assessment, says his office has received complaints about accessibility from four people who work in the building. He also says it can be difficult to drum up action to address these kinds of issues.

“[The situation] doesn’t have the heartstrings to pull,” he said. “People say, ‘Oh, you get special parking.’ I spend a lot of time trying to explain that parking is a civil right.”

‘The shortest accessible route’

Employee parking at the Oklahoma Commons is divided between the large Broadway-Kerr parking garage, across the street from the Commons, and a smaller, underground lot attached directly to the building. While handicapped-designated parking spaces exist in the larger garage, the facility itself is a block away from the office building, much farther than even the non-handicapped spots in the basement garage.

According to employees at the Department of Health and the Tax Commission who have approached the Office of Disability Concerns with complaints, those agencies have reserved the great majority of their underground parking spaces for managers and other top administrators. (OSDH and Tax Commission representatives did not respond to inquiries about how parking garage spaces are allocated.)

“That garage should be strictly disabled,” said Henderson, the Tax Commission employee who has a disability and has been trying to get better parking. Henderson said he was recently reprimanded for parking in the underground garage without permission.

The ADA requires that “accessible parking spaces must be located on the shortest accessible route to an accessible entrance, relative to other spaces in the same parking facility.”

MacMillan said that, based on ADA guidelines, the underground lot and the farther garage would be considered together as one facility when determining the shortest accessible route. So the handicapped-designated spaces in the Broadway-Kerr garage, which Henderson said are often full anyway, would not qualify according to ADA standards.

During a walkthrough of the garage around 11 a.m. on Wednesday, April 28, three of the 23 handicapped parking spaces were empty.

Henderson said he has worked at the Tax Commission for 12 years and has a handicapped-parking placard. Because of birth complications, he is partially paralyzed on the left side of his body and is prone to seizures. He said that although the Tax Commission’s former headquarters, near the State Capitol in the Connors Building, was old and continually had issues with things like plumbing and air conditioning, he never encountered the barriers to access he has seen at the Oklahoma Commons.

What he describes as a “fiasco” regarding parking arrangements started when he asked that a flashing light in the larger garage be turned off because of his seizure risk. He said building management refused, saying the light was needed for safety, so he began parking in the disabled spots in the underground garage. Two weeks later, he said, the light was turned off and he was told to return to the Broadway-Kerr garage.

In response to employee complaints, agencies housed in the building have worked with the city to have benches installed between the garage and the building, for people who might need to stop to rest during the walk. But Henderson points out that the benches aren’t helpful in inclement weather.

Henderson said that despite presenting the agency’s human resources department with a note from his doctor saying he should be allowed to park in the closer garage, he was told the underground parking was reserved for managers and “those higher on the food chain,” in his words. He kept parking in the underground garage anyway, going in through the exit.

“They thought I was ignoring them when actually I was trying to make a point,” Henderson said. “And they didn’t really care for the way I chose to show them what was right. It’s not that I’m insubordinate or anything. I just wanted them to realize, ‘Hey, I’m disabled.’ You have disabled parking spots down here. According to Oklahoma law, I can use them.”

As a result, he said, he received a reprimand and a warning that he could be fired if he continued to park in the underground garage.

He has complied, but maintains, “I don’t think it’s right.”

Tax Commission spokesperson April Gonzalez provided a statement to NonDoc.

“The Oklahoma Tax Commission follows all requirements related to employee accommodations as required by the Americans with Disabilities Act,” Gonzalez said. “The state agencies in the building have worked together to align parking procedures and address the challenges of working and parking downtown.”

Frye: ‘We’re going to make it right’

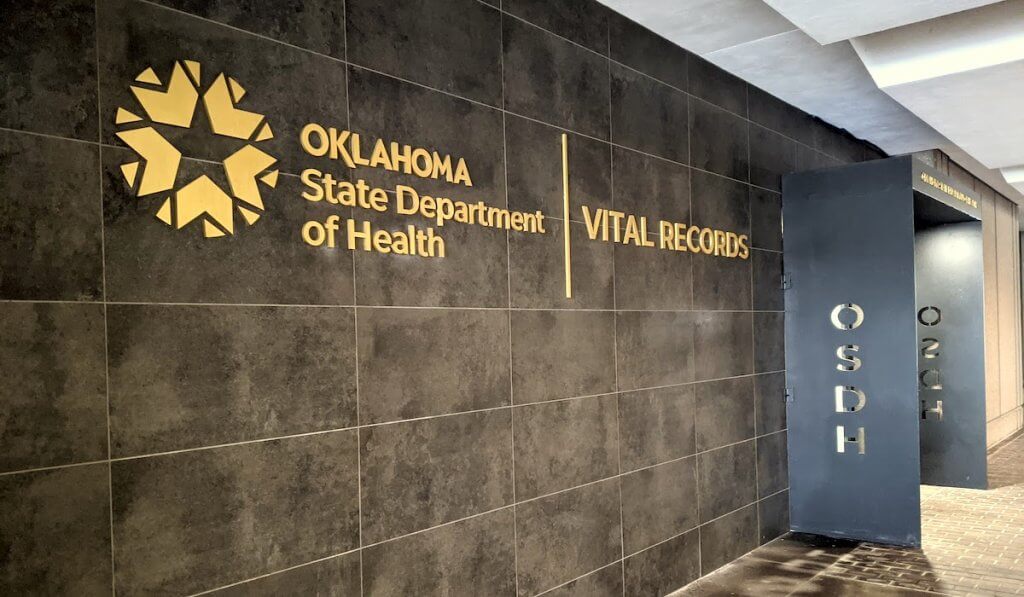

Employees with disabilities at the State Department of Health have raised similar objections to the parking situation at the Oklahoma Commons.

One OSDH employee, who asked not to be named, has a form of muscular dystrophy that requires her to use a walker and prevents her from walking long distances. Like Henderson, she gave her department’s human resources office a note from her doctor but said she was denied access to the underground garage. She was told she could telework full-time if parking in the farther garage prohibited her from coming to the office.

The employee notes that she does not believe permanent telework — when the rest of her coworkers are in the office — meets accommodation requirements because it excludes disabled employees from the workspace and the interactions that take place there.

“It’s been very isolating,” she said.

The employee, who has been at the department for six years, recently submitted her resignation largely because of these accessibility issues. Though she has had other issues during her employment, “this has definitely been the final straw,” she said.

Oklahoma State Commissioner of Health Dr. Lance Frye told NonDoc in late March that, although he personally had not been involved in accessibility issues or fielding employee complaints, the agency has been working with building management on compliance. He said he wants the agency’s employees to feel encouraged to come forward with issues.

“Absolutely I want to hear from them,” he said, “and we’re going to make sure that it is all taken care of and appropriate. We’re going to make it right, whatever we need to do.”

Rachel Klein with OSDH provided an additional statement.

“Wheelchair accessibility and parking at The Commons are in compliance with ADA standards, and OSDH’s parking policies are in alignment with the parking policies of other state agencies located in the building,” Klein said. “In the case that someone is in need of a reasonable accommodation to their parking spot, OSDH works closely with the employee to determine an appropriate alternative that fits the needs of that individual.”

Accusations of problematic handling of disability issues at the State Department of Health have also come up in a lawsuit filed March 9 by former OSDH employee Matthew Terry, who says he was fired for reporting discrimination based on disability. The suit accuses the department’s HR director, Rosangela Miguel, who is also the ADA coordinator, of prejudiced comments about people with disabilities.

The Department of Health did not comment on the lawsuit, which is ongoing.

‘Above and beyond the standards’

The legal structure of the Oklahoma Commons ownership can make it tricky to pin down who is responsible for what when it comes to accessibility. Contrary to reports that the Commissioners of the Land Office purchased the whole building, the obscure but powerful agency only purchased a number of floors, some of which were leased to various public and private entities. The State Department of Health, the Tax Commission and the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department purchased floors as well.

The building’s occupants formed what is essentially a condominium association. Although it is comprised largely of state agencies, the association is its own legal entity and is not governed by the usual strictures that apply to state agencies.

This issue came up in September 2020 when MacMillan sent the Commissioners of the Land Office a letter inquiring whether the departments in the Oklahoma Commons would be following a state procurement rule requiring state agencies to contract with organizations that employ people with disabilities for janitorial services.

In a six-page response, Perry Tirrell, the assistant general counsel for the CLO, argued that the agencies in the building are not subject to the Central Purchasing Act when functioning through the condo association, and that because of “its unique nature and constitutional mandate,” the CLO itself is also exempt.

The Office of Disability Concerns has requested an opinion from Attorney General Mike Hunter on the matter, but MacMillan said he does not expect to hear back for several months.

According to John Fischer, director of commercial real estate for the Commissioners of the Land Office, the Oklahoma Commons building was already ADA compliant when it was acquired from Sandridge.

Fixes such as the automatic door openers, he said, were not for compliance but rather because the building’s condo association has gone “above and beyond the standards.”

Addressing the issue of who gets to park where, meanwhile, falls to the individual agencies within the building, each of which has rights to a certain number of parking spaces in the garages.

Elliot Chambers, the secretary of the Commissioners of the Land Office, said the CLO wants to make sure the building is fully accessible, as far as its prerogative goes.

“At the end of the day, we all care about making sure we are in compliance, and it’s a functional and easy place for everybody to work,” Chambers said.

State agency ADA compliance ‘pretty much sucks’

Macmillan, the Office of Disability Concerns director, said the accessibility problems cropping up in the Oklahoma Commons and the agencies housed there are fairly common in among government entities.

General compliance within public agencies is “pretty bad,” he said. Recently, his office has been conducting a review of whether state agencies are following requirements to post information about their ADA coordinators and complaint processes. So far, compliance “pretty much sucks” in that area, he said.

Oklahoma does not provide much recourse for people who run into accessibility issues, MacMillan said. State regulations around accessibility give landlords and others six months to resolve problems, which often makes the whole thing “a moot point” for the people affected, he said. Some states have adopted the ADA as state law, but Oklahoma has not, so a person would have to sue in federal court to get a problem fixed in a timely manner and, even then, would not be able to recover any damages.

In MacMillan’s telling, the Office of Disability Concerns is fighting, and mostly losing, an uphill battle.

“Do you know how long it took to get the Will Rogers Building to put a new ramp in? About 40 years,” he said. “That ramp was like a ski slope. You know the guys who do the alpine jumping? That’s how steep it was.”

MacMillan said state employees and others often avoid saying anything and “just grow accustomed to it.”

“Those are the kind of things we deal with all the time,” MacMillan said.