On Tuesday, exactly 100 years after the Tulsa Race Massacre, the City of Tulsa, led by the Oklahoma Archaeological Survey and the 1921 Graves Physical Investigations Committee, will begin a full excavation and analysis of a site within Oaklawn Cemetery in search of massacre victims’ remains.

The area, known as the Original 18, was the burial site for at least 18 identified and unidentified massacre victims, according to funeral home records and other documents from 1921. Last year, coffins and remains were found there.

“I’m glad that we’re at a point in Oklahoma history, in Tulsa history and especially in American history, that the whole world is watching this process to make life a better place in the future,” Kevin Ross, chairman of the committee, said in a May 17 meeting.

The massacre was one of the worst incidents of racial violence in American history, but none of the white people involved in the violent destruction of the buoyant Black community called the Greenwood District were ever held accountable.

The recent excavations and efforts to give the victims a proper burial represent a small step toward acknowledging the past. Likewise, survivors and descendants of victims are fighting for reparations as a way to address the long-term damage done by the massacre.

Unearthing history

Approximately 300 Black residents of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, were killed when a mob of white people, with support from officials, began burning and looting businesses and homes on May 31, 1921.

Many of the victims were buried in unmarked mass graves that were largely lost in history, remembered only in witnesses’ accounts. However, remains found in a Tulsa graveyard could teach the world more about the violence that took place a century ago.

Oklahoma’s state archeologist, Kary Stackelbeck, told the 1921 Graves Physical Investigations Committee at its May meeting that the new excavation will start in segments using machinery to remove the soil and rock above the coffins. Once coffins are exposed, the excavation will continue by hand, she said.

“(We’ll excavate) very carefully, thoughtfully and methodically to ensure that we can capture as much information as we possibly can during that excavation process and so that we can document it appropriately,” Stackelbeck said.

The plan, she said, is to remove the soil around any remains but leave them in place at first so they can be accurately documented through mapping, photography and copious note-taking.

Once remains are exhumed, the next phase will be a formal analysis in a lab by Phoebe Stubblefield, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Florida whose aunt lost her home during the massacre, and her team.

Stubblefield’s team will examine any found remains in order to accurately confirm that they were, in fact, victims of the massacre.

Plans for permanent burial of the remains have not been finalized.

Calls for reparations continue

On May 20, the three living survivors of the massacre — Viola Ford Fletcher, 107, her brother Hughes Van Ellis, 100, and Lessie Benningfield Randle, 106, testified in Congress to a House Judiciary subcommittee that is considering the question of reparations for survivors and descendants of the massacre.

“I will never forget the violence of the white mob when we left our home,” Fletcher said in her testimony. “Our country may forget this history, but I cannot.”

The three survivors, along with other descendants, are plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed last September seeking reparations from the City of Tulsa and other Oklahoma government entities.

The suit describes “emotional and physical distress,” notes the loss of family wealth, and says its aim is to “recover for unjust enrichment for the defendants’ exploitation of the massacre for their own economic and political gain.”

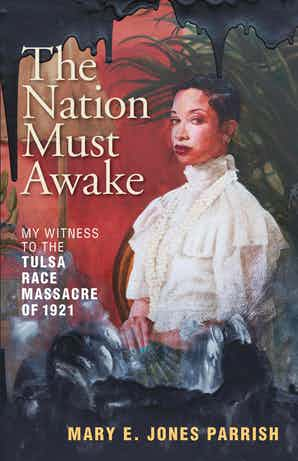

One person who watched the testimonies was Anneliese Bruner, the great-granddaughter of journalist and massacre survivor Mary E. Jones Parrish, who published a first-hand account of the events. Parrish’s book, The Nation Must Awake, came out in 1923 and included recollections from other witnesses which Parrish had collected soon after the tragedy.

Bruner commended the survivors who testified.

“They’ve gone to Congress to put their stories and their testimony before the public, before the table of power to be written in the official record — the official record of the United States of America,” Bruner said. “And what’s beautiful is, they can’t be discredited because of my great-grandmother’s book, written not later, not in hindsight, but in real-time.”

Bruner said she fully supports reparations and that they should be paid in cash.

“This is what [Viola Ford] Fletcher has asked for,” Bruner said. “Whether or not you think that reparations are due, a person of her bearing, of her character, of her standing, when she goes before Congress at 107 years old and talks about what her family endured and asks for justice — whether people think reparations are appropriate or not, don’t we believe that Mother Fletcher should end her days with dignity and with security?”

The campaign to secure financial reparations for the Tulsa Race Massacre is not new. In 2005, the U.S Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal from survivors and descendants who aimed to sue Tulsa and the state, concluding the victims waited too long to file claims.

In March, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, which was formed in 2015 and is made up of community and government leaders, released a statement “strongly” in support of reparations.

“Survivors and descendants deserve remedy and reparation for the atrocities of 1921,” the statement said. “We support the work of others who are similarly committed to the pursuit of justice through reparations and racial reconciliation.”

A 2001 report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 found that $1.8 million of damage was inflicted during the massacre — an amount worth more than $27 million today.

President Joe Biden is scheduled to visit Tulsa on Tuesday, following a weekend of local events.