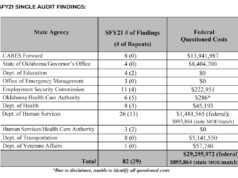

At Tractor Supply in Edmond on a recent Wednesday, grills and smokers flanked the entrance, baby chicks chirped under heat lamps, and a sign in the aisle containing horse deworming medications warned, “Despite media reports that ivermectin could potentially be used to treat people with COVID-19, these products are not safe or approved for human use and could cause severe personal injury or death.”

Nevertheless, beneath the sign was a nearly empty shelf where various dewormers containing ivermectin used to sit.

A Tractor Supply employee, Miz Garcia, said the stuff has been flying off of shelves for several months, “ever since it was on TikTok or something like that.”

Garcia said he tries to warn people that these products were not made for humans and, besides anything else, were formulated for animals about 1,000 pounds heavier than a person.

“I tell them I don’t recommend it, because those doses are really different,” he said. “Like, you can buy penicillin for dogs in our fridge over there, but it’s not the same. With this stuff, you’ll be sitting on the toilet for two days.”

Ivermectin also exists in a formula for humans — a detail that is sometimes glossed over in media coverage about people taking horse medicine — but it’s a prescription-only medication. And, although a small, vocal contingent of doctors says the human formula is remarkably effective at treating COVID-19, the medical establishment largely maintains that its efficacy is doubtful, or at least unproven. That means finding a doctor who does prescribe the antiparasitic medication can be hard. Thus, the empty shelves at Tractor Supply.

The argument over ivermectin has, like so many things these days, become politicized, and the treatment has attracted a following of vaccine skeptics in America and those who don’t put much weight in the information coming from the FDA, CDC and other official channels. In fact, the debate over ivermectin is, at its root, a debate over the nature of scientific proof and the question of how any of us know whom to trust.

From Nobel Prize to COVID conspiracy?

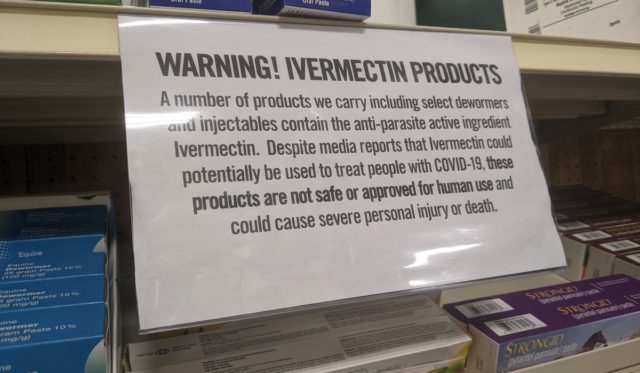

Ivermectin, an antiparasitic, was first developed in the 1970s and has been used as a treatment for everything from river blindness to head lice. It has become a common veterinary medicine as well.

In 2015, the scientists who discovered ivermectin won the Nobel Prize in Medicine. Their discovery had “provided humankind with powerful new means to combat these debilitating diseases that affect hundreds of millions of people annually,” the Nobel committee’s announcement said. “The consequences in terms of improved human health and reduced suffering are immeasurable.”

For many years, ivermectin was distributed under the brand name Stromectol, which was manufactured by Merck. Merck’s patent on the drug expired in 2014, so it has also become available in a generic version.

Besides being a well-established, widely used medication, ivermectin, because it is no longer under patent, is also cheap. For many who argue ivermectin is an underutilized wonder drug against COVID-19, this is the crux of the matter. The big pharmaceutical companies, they say, do not want this affordable, common generic drug competing with the newer, patented, lucrative drugs that are otherwise used to treat COVID.

“There’s no money to be made off ivermectin,” Dr. Pierre Kory, who is part of a national group of physicians who promote the drug, said on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast in July.

Laura Moreno, a nurse practitioner in Oklahoma City who is also currently in her first year of medical school, said she has been prescribing ivermectin to “hundreds” of patients since November 2020 and has seen remarkable results.

She said she believes open discussion of ivermectin has been suppressed because the government and drug companies, in what she called “a tag-team situation,” want to push through vaccine approvals, which she said couldn’t happen if there were treatments available.

“Once the vaccines receive FDA approval — and they don’t need to hide early treatment — I believe once they receive FDA approval, as soon as next month, then they will start approving knowledge about early treatment working,” she said.

The three available vaccines all received emergency approval by February of this year, and the one manufactured by Pfizer received full approval this week.

In fact, the vaccine approval process notwithstanding, the FDA has granted more than 600 emergency use authorizations to COVID-19 treatments, according to a January 2021 report. Some treatments later had their EUA withdrawn when studies did not show them to be effective.

According to the FDA’s guidelines for submitting an EUA application, the agency looks at “the totality of the scientific evidence available” to determine whether “it is reasonable to believe that the product may be effective for the specified use.”

Regarding ivermectin, the FDA has said, “Any use of ivermectin for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 should be avoided as its benefits and safety for these purposes have not been established. Data from clinical trials are necessary for us to determine whether ivermectin is safe and effective in treating or preventing COVID-19.”

Those who say ivermectin hasn’t proven itself as a COVID-19 treatment — including prominent health care providers in Oklahoma — would argue that it has failed on its own merits, not because of suppression.

“Ivermectin’s been an interesting thing to watch unfold,” said Dr. Jean Hausheer, president of the Healthier Oklahoma Coalition COVID-19 task force and a board member for the Oklahoma Health Care Authority. “We’ve been watching literature on that and so forth. (…) As a coalition, we’ve talked about it a lot, and we don’t recommend it.”

What makes good data?

Interest in ivermectin as a COVID-19 treatment emerged after scientists found in 2020 that it was effective at stopping the duplication of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in a laboratory setting.

An in vitro laboratory result generally is not particularly strong evidence that a treatment will work in vivo, meaning in living human patients. For one thing, in this case, the laboratory results required “concentrations considerably higher than those achieved in human plasma and lung tissue,” according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

But the lab results kicked off a number of clinical trials to determine if the drug might actually work in people. There were a few promising early results (more on that later), and some doctors, desperate for any weapon to fight the pandemic, began incorporating it into their treatment of COVID patients. The drug fell out of favor as more regimented studies failed to prove it effective.

“The data is not there,” said Mary Clarke, president of the Oklahoma State Medical Association. “It’s been continued to be snowballed as a thing, but if you go back to the original study, this was all cell-culture data. It was all in a lab, and there really is no good human study.”

Proponents of the drug say the data is there. The point of divergence is what each side considers good evidence.

There have been a number of studies on using ivermectin for COVID-19, but they have mostly been small, or were later found to have various problems with study design, and many have been based on clinical observations rather than randomized controlled trials, which are generally considered the most reliable evidence for a treatment’s efficacy and are a standard part of drug approvals.

The main champion of the drug in the United States has been a small group of physicians called the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance. The papers the FLCCC points to for evidence of their conclusions are largely meta-analyses (amalgamating the results of a number of studies) and preprints, which have not undergone peer review.

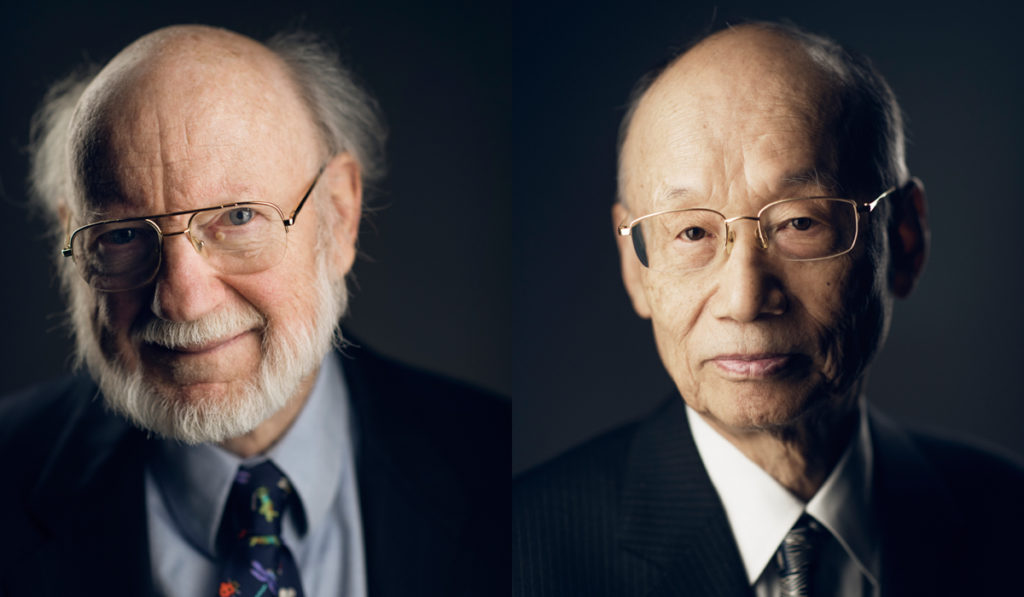

There is nothing inherently wrong with meta-analyses or preprints, but it can also be more difficult to evaluate their reliability. For instance, a preprint paper posted in April 2020 helped drive early interest in ivermectin by showing an astounding drop in the COVID-19 mortality rate. But the paper was later retracted because it was based on apparently fabricated data. (The data source the researchers used also provided faulty data last year for a retracted paper that purported to show dangers associated with taking hydroxychloroquine — remember that stuff?)

Earlier this month, a preprint posted in November 2020, which represented perhaps the strongest study in favor of ivermectin, was also retracted, over concerns about plagiarism and data manipulation. But that paper is still included as one of the studies used in the meta-analysis papers posted on the FLCCC website, arguably skewing the results.

There are currently larger-scale randomized controlled studies underway to evaluate ivermectin’s effectiveness against COVID-19, but so far there has not been what most scientists would consider definitive evidence in its favor.

In July, Cochrane, a nonprofit that analyzes medical evidence, released a meta-analysis that used more stringent criteria for the studies it included, leaving out those that were determined to have a high risk of bias or had other compromising design features, such as giving patients within the study group other drugs that varied from patient to patient. The authors concluded that there simply is not enough available evidence to know whether ivermectin works, but the best evidence they could find suggests it doesn’t.

“Based on the current very low‐ to low‐certainty evidence,” the authors wrote, “we are uncertain about the efficacy and safety of ivermectin used to treat or prevent COVID‐19. The completed studies are small and few are considered high quality. Several studies are underway that may produce clearer answers in review updates. Overall, the reliable evidence available does not support the use of ivermectin for treatment or prevention of COVID‐19 outside of well‐designed randomized trials.”

To randomize or not to randomize

The members of FLCCC might call this “randomized controlled trial fundamentalism,” saying that other types of studies, such as clinical observations and “natural experiments” which compare populations where a treatment is deployed to ones where it is not, can be equally valid.

The leader of FLCCC, Dr. Paul Marik, a professor and head of the pulmonary and critical care division at the Eastern Virginia Medical School, has engaged in this argument before. In 2017, he gained widespread attention for a paper on extraordinary results he had seen using Vitamin C to treat patients with sepsis, a condition that kills millions worldwide every year.

When randomized controlled trials showed little if any benefit from the Vitamin C treatment, Marik criticized the studies for not replicating clinical conditions closely enough.

“The question is,” Marik told NPR after one such disappointing study came out in 2020, “why does this study not replicate real-life experience and the experience of hundreds of clinicians around the world?”

Marik has also argued that, in some instances, such regimented studies are not necessary.

“Penicillin never was randomized,” he told the journalist Michael Capuzzo. “It just obviously worked. Ivermectin obviously works.”

It’s worth noting that penicillin was discovered before randomized controlled trials had become a standard practice in medicine. Before that, the efficacy of drugs was established through a slow, uncoordinated process of observation. There was no centralized arbiter such as the FDA for patients or doctors to look to for guidance, and snake oils ranging from the useless to the dangerous abounded. Also, perhaps ironically, when clinical trials were first starting to catch on, some people objected on the grounds that the approach would encourage the use of untested treatments, turning patients into human guinea pigs.

Since then, however, scientists have generally come to agree that randomized controlled trials are the gold standard of evidence, since they are designed to isolate the one treatment being tested and eliminate the chance for coincidence, bias or other unanticipated factors that might influence the results.

The results a physician sees among his or her own patients might be influenced by any number of factors — demographics, other medications being used, or even how strongly the patients believe a certain treatment will work. Randomized controlled trials are meant to eliminate those factors.

However, some proponents of ivermectin point to what they see as the potential downsides of the modern, centralized process. The demand for a randomized controlled trial is too one-size-fits-all, they argue, and they claim the process can be bent to the interests of drug companies.

Proponents also say ivermectin’s efficacy is borne out by the clinical results they have seen, and they point to places such as India or various Latin American countries that have used ivermectin as part of their official protocols for COVID treatment.

Others argue that any correlation between dropping COVID numbers and ivermectin use in these countries is weak and coincidental, and that promotion of ivermectin and other alternative treatments has had disastrous consequences in places such as Brazil, where the drugs were touted by leaders who downplayed the severity of COVID and brushed aside measures such as masks. (Brazil, along with a number of other Latin American countries, started promoting ivermectin based on the results of the retracted April 2020 preprint.)

Anecdotal evidence and personal testimony can be compelling, no matter what the studies say.

An Oklahoma City attorney who was prescribed ivermectin in December said he had not heard of the drug before receiving the prescription, but his experience made him believe the arguments for it have merit.

“I was pretty sick from COVID-19 in December for about two and a half weeks, and eventually my doctor prescribed me the human dose of ivermectin. Within a matter of 24 to 48 hours, I was feeling better,” he said, asking to speak anonymously owing to the political controversy surrounding the topic. “But it’s correlation, not causation. Maybe I would have gotten better on my own? I feel like it helped, but that’s so subjective.”

Subjectivity can creep into medical practice in all sorts of ways. And the experiences of doctors and patients can be influenced by any number of factors — demographics, other medications being used, or even how strongly the patients believe a certain treatment will work. Randomized controlled trials are meant to eliminate those variables.

A matter of trust

The fact is, most people lack the expertise and the time to make any sort of sense out of the competing studies, observations, papers, preprints, meta-analyses, websites and journals in which the ivermectin story has played out, and it comes down to whom people choose to trust.

One one side is the CDC, FDA and other medical authorities that have warned and recommended against the use of ivermectin to treat COVID-19, instead promoting vaccines and the use of masks. On the other side are the proponents of ivermectin, some of whom have found an audience through wildcat self-promotion online and have gained airtime on media outlets that position themselves as outside the mainstream.

In a time of great fear and uncertainty, most people are, to some degree, making a leap of faith in one direction or the other.

At the Tractor Supply in Edmond, a customer who asked that her name not be used because she works in the medical field (and did not want to be seen as promoting ivermectin) was buying two of the remaining tubes of horse dewormer.

“My uncle is in the hospital with COVID, fighting for his life,” she said.

She said she had heard about taking ivermectin as a prophylactic for COVID-19 and had even heard about someone with pancreatic cancer taking ivermectin and going into remission.

She emphasized that she had not decided whether she would be taking the medication, but she wanted to have some stored up in case “it works and they start pulling it from the shelves.” It was unclear whether she knew about the human formulation of the drug.

The woman said she started looking into ivermectin because the medical community had lost credibility in her eyes through a lack of transparency and she wanted to explore every available avenue.

“I don’t think anybody is trusting anything these days,” she said.

Points of agreement

You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Seriously, y'all. Stop it. https://t.co/TWb75xYEY4

— U.S. FDA (@US_FDA) August 21, 2021

The Tractor Supply customer declined to say whether she was vaccinated, but belief in ivermectin can tend to go hand-in-hand with vaccine denial and skepticism.

Clarke, of the Oklahoma State Medical Association, said she has not seen a lot of patients asking about ivermectin, but “it is the same group of patients who aren’t getting vaccinated.”

The FLCCC website says very little about vaccination, and Moreno said she feels she “can’t say anything negative about vaccines” because of pressure from the medical establishment and the government.

There are, however, two things that the competing groups of health care providers in this debate mostly agree on.

The first, surprisingly, given the amount of uproar over the topic, is that masks work and people should wear them.

“They absolutely do [work], and are critical to protect yourself,” the FLCCC website says.

Moreno said she tells her patients the same.

The other point of agreement is that people should not be taking the ivermectin formula designed for use in horses.

The FLCCC points to the higher levels of impurities in veterinary medicines. Moreno is concerned about the additional ingredients. FDA has told people to “Stop it.”

Garcia, the Tractor Supply employee, sums it up his own way.

“It’ll take everything out of you.”