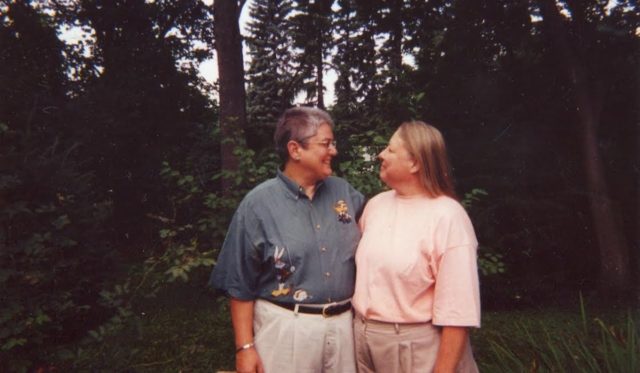

TULSA — Nearly 30 years before the U.S. Supreme Court legally recognized same-sex marriage, Sue Barton and Gay Phillips were joined in a “holy union” ceremony on Sept. 1, 1985, in the living room of their Tulsa home.

Present were four other same-sex couples, one couple’s child and a friend who had graduated from seminary and performed the ceremony.

“We were committing to the relationship for the long haul. And, in our minds, we were marrying each other even if we weren’t recognized by the state or other people,” Phillips said.

But almost 30 years later, and after a lengthy legal battle, Barton and Phillips were at the center of the 2014 court decision that legalized same-sex marriage in Oklahoma seven years ago today.

The story of their lives and their relationship encapsulates the journey for many same-sex couples of their generation in Oklahoma, who have seen an enormous shift in the laws and norms surrounding gay marriage and who participated in the fight to bring those changes about.

Living in silence

Now 67 years old, Barton grew up in Duncan, in an “unconditionally loving” family with four older siblings. Her family went to church and was “affectionate.” She didn’t know about religious-based homophobia until her 20s.

Phillips, 66, was born in west Texas and also had a loving family. She moved to Oklahoma City when she was 11 years old because her dad worked in the petroleum industry.

Growing up lesbian in Oklahoma at the time was was like living in silence, Phillips said.

“We grew up in a heterosexual world,” she said. “And it was just silent on all things GLBT.”

She was a 15-year-old Northwest Classen High School student in Oklahoma City when the Stonewall Riots broke out in 1969, launching the gay liberation movement. But Phillips didn’t know the significance of the event at the time, only hearing that there was “a riot in New York.”

“As far as anything in our media or in everyday talk, it was just void,” Phillips said.

Gay and lesbian people were rarely brought up in conversation, Phillips said, and when they were it was in a derogatory way. She was in fifth grade when she realized her name was synonymous with something other than joy.

“Some kid said, ‘You’re a homo!’ And I had no idea what that was,” Phillips said. “All I knew was whatever it was, I wasn’t it and it was not OK.”

Living in the silence, Phillips said she worried about who to let into her private life.

“When you’re a part of other marginalized groups, you can’t always hide who you are,” Phillips said. “But [when you can], that’s a burden in itself. You’re carrying around this secret.”

Partly because of this silence, neither Barton nor Phillips realized they were lesbians until their mid-20s. Before that, they went on dates and had relationships with men.

“I didn’t know when I was young that what I felt for my girl friends was different than what other people felt,” Barton said. “You know, you just love somebody and you enjoy them.”

‘An act of civil disobedience’

Barton and Phillips met through their mutual involvement in youth advocacy in November 1984, about 10 months before their living-room commitment ceremony — which would not be their last.

In fact, as laws regarding same-sex marriage and unions began to change, in the early 2000s, the couple had multiple ceremonies in an effort to gain recognition of their relationship.

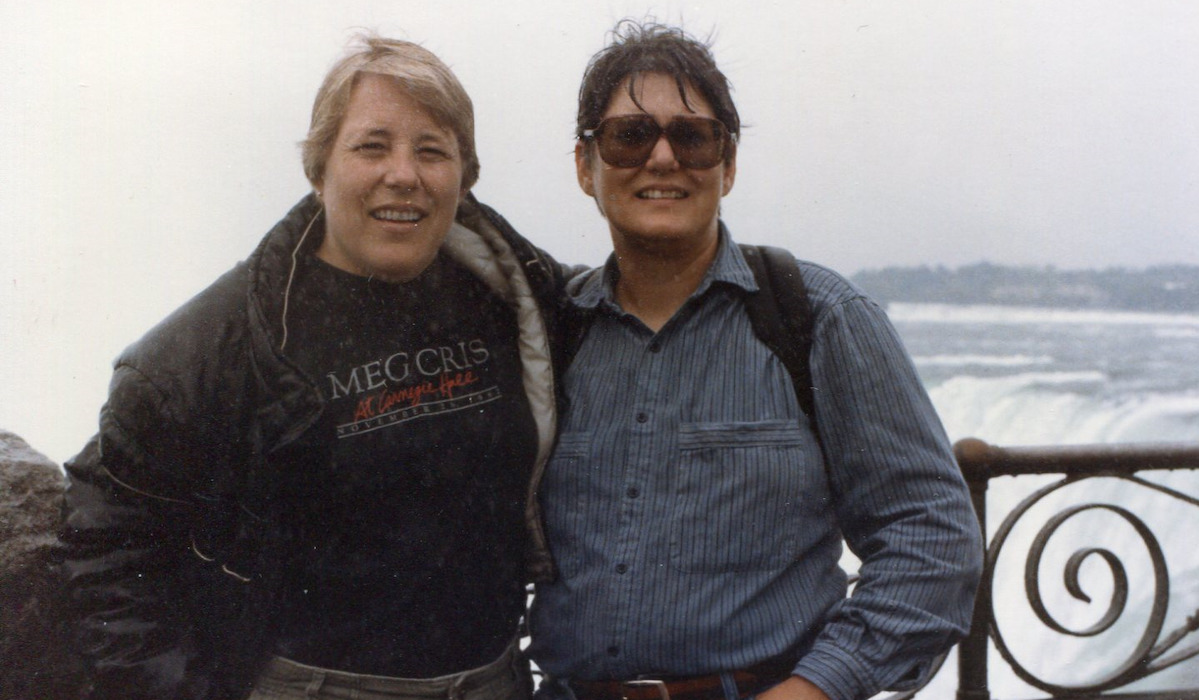

After Vermont recognized same-sex civil unions in 2000, Barton and Phillips registered for a civil union in Bennington, Vermont, in 2001 — a union that went unrecognized in Oklahoma.

When Canada recognized same-sex marriage in 2005, they traveled to Vancouver, British Columbia, to obtain a marriage license, which was also unrecognized in Oklahoma — unlike the marriage of their close, heterosexual friends who had moved to Tulsa from Canada.

Their last marriage took place on Nov. 1, 2008, in San Francisco. Barton was working in California and flew Phillips out to get married. Their marriage filing came just in time before Proposition 8 passed on Nov. 4, banning same-sex marriage in California.

“For us, it was an act of civil disobedience to say, ‘I’d get married in every state in the United States and every country that we need to because we will be recognized at some point,’” Barton said.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Life before marriage equality

The Defense of Marriage Act, signed into law by President Bill Clinton in 1996, denied same-sex couples the federal rights and protections afforded to heterosexual couples. The law permitted states to do the same.

Under DOMA, gay, lesbian or queer couples needed to go through extensive legal work to protect their relationship, making sure they individually assembled a semblance of the rights and responsibilities automatically afforded married heterosexual couples.

“Our legal papers were the thickest thing of anything we had,” Barton said.

Both partners’ names had to be included on all property titles and loans, they had to make each other beneficiaries in wills and insurance, and they had to establish power of attorney privileges over one another. Couples were not allowed to jointly adopt children, so only one partner would become a legal parent, and if that person died, their partner could lose custody of the child and their property unless they had family support and had taken legal precautions.

For a time, Barton had guardianship of her teenage cousin, and only she could sign school forms and take her cousin to the doctor, even though Phillips also helped raise the child.

Unlike many same-sex couples, Barton and Phillips had a safety net of strong family relationships.

“We had support from both her family and my family,” Barton said. “We were together in the mid-80s and ’90s, and it was treacherous for so many people. We were so very blessed to have that type of support and recognition from our families.”

‘You just know it’s your turn to step up’

The U.S. Supreme Court overturned DOMA in 2013 and federally recognized same-sex marriage in 2015. But in Oklahoma, voters had added an amendment banning same-sex marriage to the state constitution in 2004. The day after the vote, Barton and Phillips joined another couple, Mary and Sharon Bishop-Baldwin, in a lawsuit against the state of Oklahoma and the United States on Nov. 3, 2004. (The lawsuit was later amended against the U.S. and Oklahoma attorney generals and finally refiled against the Tulsa County court clerk.)

The Oklahoma Constitution amendment defined marriage as between one man and one woman and prohibited recognition of same-sex marriages performed in other states. It also had a punitive element, making filing a marriage license for a same-sex couple a misdemeanor charge.

Barton and Phillips sued for the recognition of their legal California marriage, while the Bishop-Baldwins were suing for the right to marry in Oklahoma. The two couples didn’t know each other before the case, but Sharon Bishop-Baldwin said they were always mutually supportive throughout the legal battle.

“Being in that common fight with Sue and Gay put our minds at ease,” Sharon Bishop-Baldwin said in an email. “We never worried about what they might say to a reporter or that they would somehow misrepresent the goals of the case because we were all on the same page from the start. We shared a purpose and a vision.”

Their court fight ended up lasting 10 years, and Mary Bishop-Baldwin said the two couples have become like sisters.

“We were committed to seeing this through, and our commitment didn’t waver,” she said.

Over that decade, the four women worked with multiple attorneys, who offered their services pro-bono. Other legal costs were covered by Barton and Phillips’ then-church, Community of Hope and Oklahomans for Equality. Barton and Phillips did pay for travel expenses, printing costs and smaller expenses that Phillips estimates totaled between $15,000 and $20,000.

Don Holladay, an Oklahoma attorney who joined the legal team in 2009 and remained with the case until its 2014 victory, said similar legal battles for marriage equality cost more than $6 million.

Holladay said the women were “everything a lawyer would want” as clients.

“Sue and Gay were very intelligent, very articulate,” Holladay said. “Sue had a real handle on legal issues […] and Gay was very savvy.”

Moreover, clients are the face of any litigation, and Barton and Phillips provided strong optics for the case.

“Gay and Sue have been a long-time couple,” Holladay said. “They had been very involved in parenting as a couple, so they had a long successful relationship as a lesbian couple.”

Once again, having supportive families enabled Barton and Phillps to stick with the fight. And they were in a position where they didn’t need to worry about their employment, home, cars, property and investments.

“We didn’t have as much to lose as other people did, and we were able, capable and ready for the fight,” Barton said “There does come a time in your life when you just know it’s your turn to step up.”

On Jan. 14, 2014, Judge Terence Kern of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Oklahoma, ruled that the amendment banning gay marriage was unconstitutional.

“Supreme Court law now prohibits states from passing laws that are born of animosity against homosexuals, extends constitutional protection to the moral and sexual choices of homosexuals, and prohibits the federal government from treating opposite-sex marriages and same-sex marriages differently,” Kern wrote in his ruling. “There is no precise legal label for what has occurred in Supreme Court jurisprudence beginning with Romer in 1996 and culminating in Windsor in 2013, but this court knows a rhetorical shift when it sees one.”

The decision was upheld by the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver on July 18. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the decision, which effectively legalized same-sex marriage in Oklahoma on Oct. 6, 2014, when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the decision.

Between then and Dec. 7, 2014, court clerks issued more than 3,200 licenses for same-sex marriage in Oklahoma.

‘A whole new world’

Barton and Phillips have now been together for 37 years. Like many married couples, they say they have built their relationship on commitment, dedication, communication and understanding.

Now in their late 60s, they spend retirement with their three dogs. They are involved with the Dennis R. Neill Equality Center. Barton likes to fish. Phillips teaches a sociology class at Oklahoma State University’s Tulsa campus.

Public support for same-sex marriage has steadily increased since the mid-1990s, but “the fight is far from over,” according to Holladay.

Approximately 138,000 Oklahomans identify as LGBT and lack protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Oklahoma placed 29th in a USA Today ranking based on the numbers of hate crimes, protective laws and LGBT population.

RELATED

LGBT in Little Dixie part two: ‘Most bigots are cowards’ by Michael Duncan

Still, Barton and Phillips say it’s “a whole new world” for them and other same-sex couples these days. The marriage rights they fought for have been won, and younger generations of LGBTQ people have models, words, expression, positive images and representation to normalize their experiences and identities.

“I just think there was a significant difference,” Phillips said. “It’s different for them to be able to come out. And that’s not to say that they still do not experience discrimination and hate harassment.”

Phillips said she feels more comfortable and protected now than ever before.

“So many people I work with and come in contact with are supportive [of LGBTQ people], and even the ones who don’t like gay stuff, I don’t feel threatened by them anymore,” Phillips said. “I feel permission if people yell at me that I can stand up for myself.”

Barton and Phillips have a wider social circle with “gay” and “non-gay” friends, old and young friends, and even friends who are theologians.

“Living now, I don’t even think that much about it anymore,” Barton said. “When I go out the door, it’s like I’m not a lesbian going out anymore and I have to be careful. I’m just me going to work or going to the grocery store.”