Reggie Wassana, governor of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, was recently reelected to his second term in November. During that same election cycle, the Cheyenne-Arapaho citizenry voted to amend the tribal nation’s constitution to decrease the blood quantum requirement for citizenship from one-fourth to one-eighth.

Blood quantum is a concept that measures the fraction of Indigenous blood that a person possesses. However, the measure is historically controversial, as it limits tribal citizenship and the benefits that accompany it.

A graduate of Weatherford High School, Wassana grew up in rural western Oklahoma. He graduated from Southwestern Oklahoma State University before working for his tribe as a director for the Department of Housing. After working in housing, Wassana was “talked into politics” by other tribal citizens and ran for the District 3 legislative seat. After serving District 3, he was selected as speaker of the Legislature, before eventually running for governor.

Wassana recently answered questions regarding his path into politics, the blood quantum requirement change within the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes and other ongoing developments within his tribe and Indian Country at large. Headquartered in Concho, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes are a united, federally recognized tribe formed in 1937 by Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho people.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for style, clarity and length.

Tell us about yourself. Where did you grow up? What is your professional background, and why did you get involved in politics?

I grew up in rural, western Oklahoma, north of Weatherford, Oklahoma. I graduated from Weatherford. I went on to school to OU for a year. I went to Southwestern and graduated there at Southwestern. My grandparents lived on their own land as part of the allotment. They gave my mother a few acres to build a house through the Indian Housing program. So I pretty much rooted down in western Oklahoma. I grew up around a lot of relatives. We lived out in the country. Like I told people, I hardly saw anybody light in the summer, because we always just hung out with all of our relatives. So in the upbringing circle, I just hung out with our cousins and relatives the whole summer after school.

After I graduated, I went to work for the tribe. I worked in a planning department. Some commissioners of housing wanted me to apply as a director. I applied. I got the job. Then when I got into housing, I think we were pretty successful. We did a lot of things: a lot of renovations, purchasing homes. We built some buildings for the tribe. So I think people kind of talked me into politics. As far as, “You did this, you did that, we need somebody to help us at the tribe.” So I think the tribal members’ influence after I worked for housing, with all the good things that we’ve accomplished, people wanted me to carry that forward into the tribal side of politics.

So I eventually ran. I was young at the time. Some people said, “Wait till you get a little older, a little seasoned and when the time is right.” I tried to run two times prior to that, and I couldn’t get on the ballot. For whatever political purposes, some people didn’t want me on the ballot, because I think some people felt that I could win, and I would win if I got on the ballot. So I was kind of kept off the ballot, more or less. When I did get a chance to run, I ran as a district representative for the Legislature in Cheyenne Arapaho District 3 out in my area. I won. I was voted on by the rest of legislators as speaker. I served as speaker of the Legislature for two years. But two years into my term, the governorship came up. I ran for that. We won. And just recently, I ran for my second term, and I won this past November. So we’ve been pretty successful.

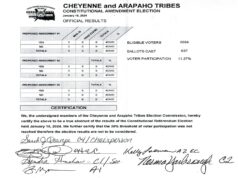

You and Lt. Gov. Gib Miles were recently reelected in the November general election. In the October primary election, Cheyenne and Arapaho citizens voted to lower the blood quantum requirement from one-fourth to one-eighth. What sort of changes has the tribe seen or do you expect to see since that referendum passed?

That’s been discussed the last 20 or 25 years. Even 20 years ago, when people would bring it up, there were still a lot of people against it. They didn’t want to get a lesser degree of services or a revenue share from the casinos. So it was always opposed. I think a lot of older people had passed on in the newer generation with children that were quarter-blood or less. They stepped up and came out, voted and passed it, but it was eventually going to go that way. Because the tribe’s enrollment, the majority were quarter bloods, which that was our blood quantum. I believe those quarters were wanting to see their kids or grandchildren get on the roll. So it was eventually going to pass.

Dec. 1., we started taking applications for enrollment, in which there’s some due diligence and vetting on making sure that they are enough blood, their parents are tribal members, or however they can come up with the eighth degree. So they will be patiently going through those applications. I expect in the next two to three years, we may have 3,000 to 6,000 more tribal members on our roll, and then maybe even more than that. There’s a lot of people who are out there who will not only be birthed at an eighth, but they’ll already be adults. There’s already adults wanting to move their citizenship from one tribe to the Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes.

Because the Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes are made up of two distinct tribes with their own individual histories, do you believe the blood quantum issue has more sensitivity surrounding it within the tribe?

I think it all comes down to a pride in heritage for some of the older people. There are some people in the tribe that wanted the blood quantum to remain because they felt that, if we open it up, maybe our future tribal citizens may not look like our past generations. And they didn’t want to accept that. But times are changing, things are changing. The philosophies are changing with the tribe. The outlook is changing. At some point, the majority — which would be quarters, or halves — would have their say. I don’t necessarily believe that the Cheyenne or the Arapaho look at this as a Cheyenne-Arapaho blood issue. They look at it as a membership issue. The majority of the younger people — the millennials, Generation X — I don’t think they weigh a lot on what tribe you are, whether you’re Cheyenne or Arapaho, because a lot of tribal members are part Cheyenne and part Arapaho. You do get to share both bloods to make an eight. You don’t have to just be an eighth Arapaho or an eighth Cheyenne. You get to share that blood to become an eighth. I think a lot of people looked at it as maybe we were diluting the blood too thinly with an eighth.

Twenty years ago, I would tell people it was going to change one day. That day came. As these years go by, you’re going to see more and more people be an eighth on our tribal membership rolls, or a quarter. Because we can’t marry each other. We have to go outside and and go out and find other tribal members or other non-Indians to marry because we’re all going to be related somehow, in that degree. It was probably the time that one-eighth came in. It did pass. If we did it next year or two or three more years later, it would probably pass by an even bigger margin. But it was coming. That day was coming that the blood quantum would be opened up.

At the Sovereignty Symposium, you had mentioned that the tribe is looking to purchase land in Colorado, where the Cheyenne Tribe originated. With the expected increase in enrollment, is land expansion something the tribe is looking into?

Yeah, with the elections we had, we put a lot of things on hold until we could find out if we were reelected. Originally, we were around the Rockies, like I said, around Denver. When gold was found, we were more or less removed from that area. And part of the goal is to go back to Colorado and purchase some land and build a resource center or economic development. We have tribal members up there who would like to see some services moved into that area. I believe that we have just as much right — and as part of our historical area there, Colorado and Denver — that we are looking to do that.

As the governor of a sovereign tribal nation whose territory has not been directly connected to the Supreme Court decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma, what positive impacts do you see from the decision on your citizens? What concerns do you have?

I think they acknowledged the fact that the trust issue was not removed. It was tribally based and treaty based — that’s how they came up with the McGirt decision. But I think just the acknowledgement — that may have opened up other areas that said that Congress — they ratify the treaties — but some treaties, they didn’t take away that land issue or that trust issue.

So I think a lot of tribes are going to be looking at those kinds of things. It was a positive ruling, as far as tribes go, to say, “Hey, there might be some other issues out there that weren’t ever examined.” Because, you know, we all think that things have been looked at, cut apart and examined. But it just goes to show there may be other issues. I think it was a good thing as far as the acknowledgement that there are still some underlying issues out there in Indian Country that may have been overlooked. But we’re not part of the McGirt decision. We’re in western Oklahoma. That involved those eastern tribes on that side. The state and the tribes are having their discussions on how they’re going to handle that.

The economy of your tribe has expanded substantially over the last 20 years. What has driven that, and what benefits and challenges exist now that may not have existed a couple decades ago?

Well, of course, the advent of casinos. We have six casinos. I’d say we do well. We provide services. Back in the early ’90s, before the advent of casinos, we actually had 70 percent unemployment. So what has definitely changed is that there is now income in the household. The unemployment has gone down drastically. Instead of 100 people standing in line for one job, you may have 10 jobs for one person. So that ratio has actually reversed itself from no jobs to jobs, people having household income where they used to actually rely on the state support, whether it was food stamps or some type of monthly assistance from the state. So I think we’ve taken a lot of people off the state assistance rolls. A lot of people got jobs. A lot of people can provide for their families. They can buy homes, they can buy cars. So I think all in all, not only did we provide more services and help our elders, but I feel we stimulated the economy of Oklahoma. Once you get families to go out and buy cars, you keep people employed, they buy homes, they buy furniture, all those durable goods, all those services, whether it’s food, gas or anything, we put more money out there in the economy for people to keep their jobs outside of the casino jobs. So it definitely has changed.

In the ’90s, I remember, our budgets were minimal. Now our budgets are in the millions. We’re able to assist the elders and help provide them with with good meals, health care. Just the longevity of our tribal members probably went up three to five years simply because it’s a little bit easier to live than it was in the ’80s and then in the early ’90s. But definitely with job growth and revenue, that has definitely maneuvered the tribes in positions that they probably would have never been in without it.

Many people have a hard time distinguishing between the situations facing different tribes. What should Oklahomans know about the Cheyenne and Arapaho specifically? What should people understand about your tribe and the largest tribes based here in Oklahoma?

Our tribe is still real culturally based. We still have our ceremonies. We still have our cultural events, and we still practice our traditions. That is something that some tribes don’t do a lot of, and a lot of it is because of the location. Some of the tribes are more successful because they are around bigger population bases. But I feel that our tribe still has a lot of heritage and still does a lot of cultural and ceremonial events that we’ve practiced over the past 100 years. One of the things that people should understand is that we’ve maintained our culture, our heritage and our ceremonies, even though we’ve managed to kind of get into the mainstream of society. But you know, we still have work to do on keeping that, but we still have it. But we need our younger people to help carry that forward as well.

If you had to compete in one sport or game for a $1 million prize, what competitive activity would you pick?

Well, if I was 6’4″, I’d probably play basketball. I love sports in general. My first love was football. I enjoyed pickup games, basketball. I played golf. I played checkers. I played chess. I mean, you name it, I’ll play it. I’ll do it. And I think that was just always the competitive nature in me. I mean, I loved football. I thought, you know, like every kid, I wanted to be a professional football player. I enjoy basketball, too. I ran cross country. That takes a little bit of effort, especially when you got to go and run against a lot of people. But I like it all. I enjoy all sports.