Those hoping for change in Oklahoma should look to its past.

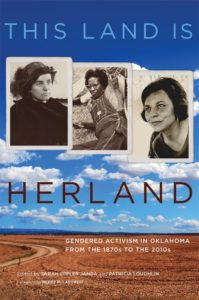

A new book, This Land is Herland: Gendered Activism in Oklahoma from the 1870s to the 2010s, edited by Sarah Janda and Patricia Loughlin, provides an important addition to our understanding of this state and the people who shaped it. It features the stories of 13 women activists from across the political spectrum who played key roles in Oklahoma history.

It is full of surprising and forgotten tales and is also a good companion to Janda’s book Prairie Power, which I reviewed recently and which covers the history of student activism in Oklahoma in the 1960s and 1970s.

Like that book, This Land is Her Land does not shy away from presenting uncomfortable, complicated truths, even if they don’t fit into preconceived political notions.

Power and motherhood

One theme that emerges in these histories is of women rising to positions of leadership and power by disavowing activism aimed at giving women access to such positions.

For instance, Kate Barnard, who in 1907 became the state’s first commissioner of charities and corrections (then the only position an Oklahoma woman could hold), was primarily focused on addressing issues affecting children, such as child poverty, child labor, the conditions faced by Native American orphans and juvenile justice reform. These issues brought her into alliances with progressive and socialist causes. She was also committed to public education and women’s welfare. Barnard picked her battles and won victories against sexism and Gov. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray’s racism. She also prioritized the fight against the horrific conditions in state prisons and for mental health care.

Yet Barnard did not participate in the fight to win voting rights for women. She was not anti-women’s suffrage, but she considered herself an “a-suffragist,” who did not take a stand on that issue because she was committed to so many other causes.

A contrasting example is Alice Robertson, who was a conservative Republican and the vice president of the Oklahoma Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. Even so, she became Oklahoma’s first congresswoman in 1921. She promoted “conservative maternalism,” a philosophy that promised a “Nation of Great Mothers.”

Her rhetorical prioritization of motherhood while pursuing political power foreshadowed a narrative adopted by the state’s first and only female governor, Mary Fallin, who proclaimed, “My children are more important to me than any office I might hold.” For Fallin, the book argues, motherhood became a “conservative political strategy,” and for three decades, starting with her election to the State House in 1990, she never lost an election.

Oklahoma’s intersectional history

The majority of women whose stories are told in This Land is Herland were Native American or Black. Native Americans such as Lilah Lindsay and Rachel Caroline Eaton focused on education and the preservation of tribal cultures. LaDonna Harris, the wife of U.S. Sen. Fred Harris, made headlines as the founder of the first intertribal nonprofit political organization.

Harris was active in the civil rights movement and other causes, but, rather than leading protests or running for political office, she cultivated relationships and built networks, working with organizations like the National Urban Coalition and Common Cause and through the Office of Economic Opportunity, which operationalized President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society.

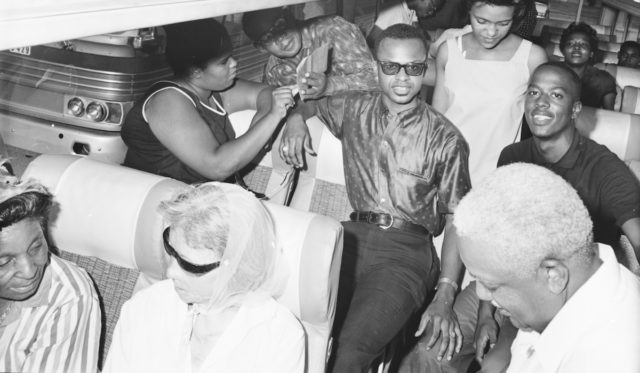

Black leaders such as Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, who integrated the OU College of Law in 1948, and Clara Luper, who started the nation’s biggest sit-in movement in the 1950s, are already well known. But I was struck by how much I learned from the chapters on their lives. Similarly, I knew little or nothing about California Taylor, an entrepreneur who contributed much to the all-Black town of Boley, or about Barbara “Wahru” Cleveland, who founded Herland Sister Resources and fought for lesbian rights.

Also, I’ve long known about Wanda Jo Peltier Stapleton’s time in the Legislature, but I was stunned by how much I didn’t know about her work for the Equal Rights Amendment.

My favorite chapter, about Rosie Gilchrist, is an ideal case study of “intersectionality,” or how narratives about race, gender, inequality and injustice interconnect.

Gilchrist, a white, suburban woman, nearly died in a house fire in 1959 and ended up with third-degree burns on most of her body. Recovering at Baptist Hospital, she became close to the Black nurses who cared for her, especially one named Mrs. Fulbright.

After being released from the hospital, Gilchrist was not welcome at her church because her wounds were “too disruptive” and “scared the children.” So she went to Mrs. Fulbright’s church, Calvary Baptist, where they had long been praying for her.

These connections led to Gilchrist participating in Clara Luper’s anti-segregation campaign, and in 1963, she went to Martin Luther King’s March on Washington. After returning, she tried to sell her home in Warr Acres to a Black man, an act that her husband, neighbors and city officials used as evidence of insanity, and she was locked up for five years at Central State Mental Hospital. It took quite a coalition of officials, and the “interconnectivity of racial and economic motives” to maintain the lie that she needed to be institutionalized when she clearly was sane.

She was eventually released thanks to the intervention of Sen. E. Melvin Porter, Oklahoma’s first Black state senator.

The stories told in This Land is Herland are not always easy to read or acknowledge, but they are important, just as it is important that we stop shielding ourselves from cruel realities we do not want to face. We cannot hope for real reform until we come to grips with the narratives of This Land is Herland and Prairie Power.