ENID — I find it intriguing to get out of town, and especially so when the destination is somewhere I once lived.

As a result, I was glad to have the opportunity to hit the road for NonDoc’s Enid Envoy this summer. It provided an occasion for Garfield County residents to meet us and our Enid News Ambassadors — Lisa Bland-Selix and Sally Clickner — who introduce NonDoc to those unfamiliar with our independent journalism. While NonDoc holds outreach engagement events to gain new readers and followers, we also aim to listen to folks about news coverage priorities and local issues that deserve attention.

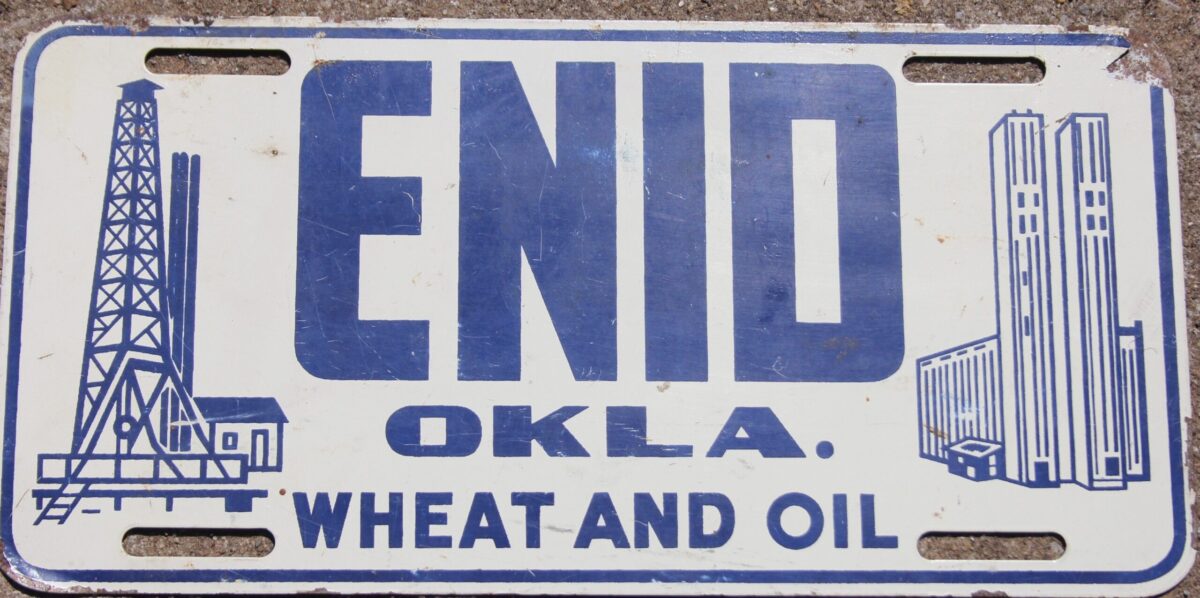

Enid is a regional shopping and health care center for northwest Oklahoma and southern Kansas. Vance Air Force Base, with its mission of training pilots, and large grain-storage facilities remain the economic mainstays for this city of about 51,000. Surrounded by grain fields, windmills and oil wells in a mostly rural section of the state, Enid prides itself in providing some big-city amenities — such as a symphony orchestra, a community theater, branch campuses for a state university and a junior college, medical facilities and an airport. It also deals with some big-city concerns, such as how to help the homeless, attract and retain health care professionals and land businesses that will provide good-paying jobs for the future.

Until several years ago, Enid boasted a mall with big stores like Dillard’s and Sears, and it attracted people in the area who wanted to go shopping or see a movie without making a long drive to either Oklahoma City or Tulsa. With local leaders long understanding the importance of water for residents and businesses, the city is completing a major water expansion project to meet future needs. They’re optimistic those needs will include a new tenant for property once occupied by the Northern Oklahoma Resource Center, a facility for the developmentally disabled that — at its peak 80 years ago — had 1,200 patients.

During the past year, Enid has often made headlines, including for the recall of an Enid city councilman with ties to a white nationalist group, the construction of a solar plant southeast of Enid, and the possibility of a casino west of town. Adjacent to the NORC campus, police and the Department of Human Services looked into allegations involving abuse of residents at the Greer Center, a facility for intellectually disabled people with mental illness. The charges were abruptly dismissed, causing several residents to protest. And then there was the sad news of an Enid native, Louisa McCune, dying unexpectedly at the age of 54. I first met Louisa when she started as a reporter at the Enid News & Eagle, and we stayed in touch through the years — mostly talking about dogs we rescued and Oklahoma politics — as she went from writing for magazines in New York to her time as editor in chief of Oklahoma Today through her tenure as executive director of the Kirkpatrick Foundation.

Enid was the first place I lived in Oklahoma, arriving there 43 years ago this month to work as a reporter for the Enid Morning News and Enid Daily Eagle — two newspapers owned by two local families in one operation. One served as a morning paper, and the other was distributed in the late afternoons back when people relied on such a thing as an evening newspaper.

I had actually heard of Enid before finding it on a job posting. In 1973, while I was a student journalist at the University of Missouri-Columbia, the daily dose of stories on the growing Watergate scandal was interrupted by an item about a record rainstorm in Enid. It was a lot of rain. The most rainfall in one day in Oklahoma — 15.68 inches at Enid. Some say 75 percent of the rain fell in about four hours, which triggered the Oct. 11, 1973, Enid flood.

My first trip to Enid proved to be an adventure. As I faced the setting sun near the end of my six-hour drive from Rolla, Missouri — where I had worked two years as a reporter and editor of a daily newspaper — I was fascinated by structures I couldn’t make out. That was one of my first questions when I arrived for the job interview — my first introduction to large wheat elevators, which were the basis of Enid’s nickname as the “Wheat Capital” of Oklahoma and the United States.

The first question I asked is whether any of Garfield County’s three commissioners were involved in Oklahoma’s county commissioner kickback scandal. A national news story, even cartoonist Garry Trudeau mentioned it in his Doonesbury comic strip. I was told the three commissioners had told the paper’s reporter they had avoided the temptations. Two weeks later, after accepting the job and returning to Enid, I picked up a copy of the Enid Morning News. A giant headline blared that Garfield County’s three commissioners had accepted kickbacks. It turned out that Bill Price, the U.S. attorney who headed up prosecuting what was then the largest political corruption case in the U.S., had seen the prior story about the commissioners, prompting him to call and advise them they had better call the reporter back and tell the truth or else he would prosecute them with no chance of a plea bargain. They heeded his advice and recanted their denials.

Enid had an abundance of news during my stay there, from the 1983 shuttering of the Champlin refinery to bank closures during the oil bust of the mid-1980s to new life for the old Phillips University campus when it became a satellite campus for Northern Oklahoma College in 1999.

Lack of movie theater, troubled mall among local concerns

About 40 people showed up for a wide range of conversations. NonDoc editor in chief Tres Savage challenged participants to test our knowledge of Enid history and trivia. We thought we could connect on a few, but we went down swinging on the first question tossed our way: Name the artist who has a mural displayed in the State Capitol. Answer: Sara Scribner, whose Making Her Mark can be found in the Hall of Governors on the second floor of the Capitol. Incidentally, Sara and her husband, Shane, bought the building we were in about 20 years ago and had operated an art gallery in it to display works of Oklahoma artists.

Trust in journalism proved to be a main topic of concern among attendees. Many said they trusted the local newspaper, but sifting through the scores of news items on social media made them feel like they were drowning in waves of uncertainty.

“In Enid and everywhere, we’re really concerned about the amount of disinformation in what sources can be trusted and how do you deal with proliferation on social media of information that’s just a little bit off base and then gets skewed a little bit more off base each time as we’re told,” said Jeff Funk, who retired last month as publisher of the Enid News & Eagle.

Funk spent 47 years in the newspaper industry and had served as publisher of the Enid paper since 2001. He first retired in 2021 but returned last August on a temporary basis. He also had a front-row seat to some of the issues facing the city. Shortly after he retired in 2021, he filled an expired term for about four months on the Enid City Council.

Issues that Funk dealt with in both roles remain topics of discussion today. For instance, Enid lacks a movie theater, and its mall offers just a sliver of its former fare.

Oakwood Mall, when it opened in 1984 on the west side of town, boasted movie theaters and anchor stores such as Dillard’s, JCPenney and Newman’s. Back then, the mall faced concern it would devastate the downtown area, as two of its largest stores — JCPenney and Newman’s — moved into the mall, and eventually Sears moved from downtown to the mall to replace Newman’s. The mall boasted about 40 stores when it opened and offered a food court with 12 vendors. For 30 years, it attracted shoppers from northwest Oklahoma and southern Kansas, but it never reached full occupancy of 90 outlets, and by 2020, all of the anchor stores were gone. It still operates today, but its fate has mirrored many malls around America, with only about a dozen businesses, a church and a handful of food vendors open within.

Since the movie theater chain closed its operations about 10 years ago, residents have heard rumblings that another theater would open elsewhere in Enid, but nothing has developed.

“To what extent does government incentivize private development, and how far can government go, and (…) at what point do you say it’s not the city’s role?” Funk asked during the July 30 event. “Do you say it’s not the city’s role to be operating a movie theater or operating a hotel? No, you can incentivize entertainment, you can incentivize an event center complex, just like you pay for parks or you pay for staff to come in (for) concession stands at the ballparks.”

With no movie theater and the mall a mere shadow of itself, Enid many residents agree that the city needs quality-of-life attractions. Those items are important for residents but also key in attracting industries because businesses want to be able to recruit and retain employees. As Oklahoma City infamously learned in the early 1990s, it’s difficult to recruit industry if a community offers little to do where people would live.

So, a city like Enid has to wrestle with whether to provide incentives to a quality-of-life asset, like a movie theater, as it might to a company that considering locational investments, Funk said.

“It’s a challenging business to be in, in a day and age where you can get entertainment in a lot of different places,” he said.

Health care, homelessness key issues in Enid

Health care has become another quality-of-life concern, said Janet Cordell, who has been a registered nurse for more than 40 years. Cordell retired 18 years ago, but she still is doing volunteer work with Enid Community Clinic, American Red Cross and Enid Street Outreach Services.

Cordell taught part-time at Autry Technology Center and still works with the volunteer nursing program there. She was a Hospice Circle of Love nurse for 20 years and has been the director of nursing at a local nursing home. Additionally, Cordell taught the first prenatal classes at Northwestern Oklahoma State University-Enid and worked 25 years at the OU Family Practice Residency program.

“I say in 10 or so years, Enid’s going to be a desert for general practitioners — and all of northwest Oklahoma,” she said. “All the guys I trained are now starting to retire, and we don’t have anybody to replace them.”

Since Cordell “retired,” she has coordinated services at Enid Community Clinic, which serves the needs of those without the ability to pay for medical care. She has volunteered for Remote Area Medical‘s large-scale free clinics, and she hopes the Tennessee-based organization may bring its free dental and vision care programs to Enid in the next year or two.

Cordell also worries about the low-income, hungry and unsheltered people in Enid and the surrounding area, which is the focus of the Enid Street Outreach Services organization.

“Our city commissioners just don’t want to look at the problem,” Cordell said. “I mean, you know, we keep them out of sight. We close all the bathrooms, and we kick them out of downtown. If we keep them out of sight, then they’ll be out of mind. And our homeless population is growing. And, you know, the only shelter we have is Salvation Army.”

Water always an important issue in Enid, northwest Oklahoma

During NonDoc’s event, State Sen. Roland Pederson (R-Burlington) and State Rep. John Pfeiffer (R-Orlando) stopped by and visited with constituents, with Pfeiffer sticking around afterward to take questions from about a dozen people for nearly an hour.

Most of the talk centered on controversial State Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters, but the discussion eventually drifted to other topics, such as improving broadband access in the state, energy sources and water.

“It’s those kinds of infrastructure things that are going to help rural Oklahoma and western Oklahoma grow. We have to figure out what’s the next best strategic investment,” Pfeiffer said. “And those sets of things aren’t necessarily as fun to talk about. Nobody wants to talk about [Oklahoma Water Resource Board] water grants, but it’s extremely important to these communities and where we go from here in helping us grow and sustain what we have.”

Pfeiffer hinted at changing public perceptions about renewable energy projects. While wind development was lauded for decades as revenue-generating investment for the future, signs line highways south out of Enid opposing new solar energy development.

“Unfortunately, at least to me, it looks like so many of these decisions (…) coming out of Washington, D.C. [aren’t] necessarily based off what’s the most prudent. It’s based off political decisions. Is solar and wind a good way to diversify? Maybe, sure. Do we need to be adding it at such a rate? I don’t know,” Pfeiffer said. “I know the amount of wind production we have here in the state of Oklahoma has been helpful, but it’s also hurt us to the tune that we’re losing gross production dollars in natural gas because we’re not burning as much natural gas. We’ve got to take a big hard look at how Oklahoma participates in the Southwest Power Pool, how much we let the Southwest Power Pool dictate what kind of energy we’re producing in Oklahoma, and make sure that we don’t throw our entire tax system out of whack, because (while) wind and solar are taxed on the ad valorem base, oil and gas are taxed on the gross production tax base, which goes to the state.”

As Pfeiffer noted, water has always been an important issue in northwest Oklahoma, and I would know.

In the fall of 1981, I had been at the Enid Morning News and Enid Daily Eagle for a couple of months covering county and city government meetings. Another reporter at the paper, who, with a copy editor, ate most dinners at a popular downtown cafeteria, asked me why I wasn’t covering the real Enid City Council meetings. I asked what she meant, and she said council members and city staff would gather in an upstairs meeting room at the cafeteria for dinner about an hour before the posted council meetings. No agenda for these dinner sessions was posted.

The Oklahoma Open Meeting Act requires that public bodies post a notice any time a quorum of a public body gets together. If any public business is to be discussed, that must also be included on an agenda.

So, on the evening of the next Enid City Council meeting, a photographer and I went to the cafeteria about 90 minutes before the meeting. We watched as we saw more than half of the city’s six council members — along with the mayor and city manager — go through the cafeteria line and head upstairs to a banquet room. A few minutes later, we followed. First, we had to unhook a sign draping the stairs forbidding entrance. Then, we sat on the stairs and heard them talking of a plan to deceive the public.

The city was trying to develop a $40 million water project that would consist of bringing in water from wells about 20 miles west of town. Two landowners had refused to consent to selling land for the pipeline, so city council members at the dinner meeting planned to announce during the night’s posted meeting that the city was abandoning that effort to instead pipe in water from Kaw Lake, about eight miles east of Ponca City. They had no intention to get water from Kaw Lake, but their hope, they said, was to make the landowners panic, come to terms and sell their land to the city.

Hearing enough, we went up the stairs and into the secret meeting. At first, the attendees said they were just eating dinner and not discussing city business, but eventually they realized we had heard their discussion. From then on, the Enid City Council posted its dinner sessions, and they were open to the public. The landowners eventually settled with the city, and Enid’s water project went on as planned.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

‘There’s still a lot of civic pride’

As I drove into Enid for our late-July event, I noticed several large pipes laying in a field on the east side of town. Water demand for the city has only grown since the water project 40 years ago, and now the city needs another water source. This time, for real, Enid is going to tap into Kaw Lake. Work on the nearly $300 million project, which includes a new water treatment plant, has been ongoing since 2021 and should be completed in about a year.

So, I thought, some things do come around full circle.

Despite the challenges Enid faces, residents maintain a can-do attitude that has long defined the city.

Beau Simmons, who had just recently been named deputy regional editor for CNHI Oklahoma and executive editor of the Enid News & Eagle, came by our event to visit with our team members and hear what folks had to say. While he continues to serve as executive editor of the Stillwater News Press and leads the Woodward News, Simmons said he has been impressed with what he had seen so far in Enid.

“It’s just a little bit different than a lot of the other places I’ve been,” Simmons said. “I mean, it’s more conservative. But they’ve got [these] real sort of business-savvy folks running the place. It’s like there’s still a lot of civic pride in all the stuff you think about.”

Closing out his newspaper career, Funk said he and his wife, LynnDe, are staying in Enid, which he thinks will continue to grow and overcome its challenges.

“We love the community,” Funk said. “And when you’re involved in civic affairs, you volunteer for different projects to try to make Enid a little bit better place, to improve the quality of life, to open up some opportunities for fun things to do and make it a more enjoyable place to live.

“And, you know, part of that selfishly is because you want your kids to graduate and come back and live here. You love to have grandkids here. We’ve been blessed that we have that. So that’s an attraction here in town, but that’s part of what motivates you to get involved in the community and make it a little bit better.”