Tucked away on Page 547 of the 942-page Farm, Food, and National Security Act of 2024 is a provision that would permanently prohibit the federal government from returning Fort Reno‘s land to the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, a pair of sovereign nations combined by treaty with the United States in 1867 who maintain they are the rightful legal owners of the western Oklahoma property.

While that section of the bill makes no reference to Fort Reno, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes or even the state of Oklahoma, its future will dramatically affect all three.

“It’s disappointing, to say the least,” Cheyenne and Arapaho Gov. Reggie Wassana said in an interview. “All across the country, senators and congressmen are helping the tribes get their ancestral homelands returned, and we’re kind of feeling like ours are being actually kept away intentionally.”

The congressional proposal stands as the latest obstacle for the tribes’ century-old effort to reclaim 9,500 acres of Fort Reno’s footprint west and north of El Reno. As other tribes across the country have succeeded in negotiations to restore their historic lands, Wassana and others are working to highlight decades of deliberate efforts by Oklahoma politicians to keep Fort Reno under the federal government’s control.

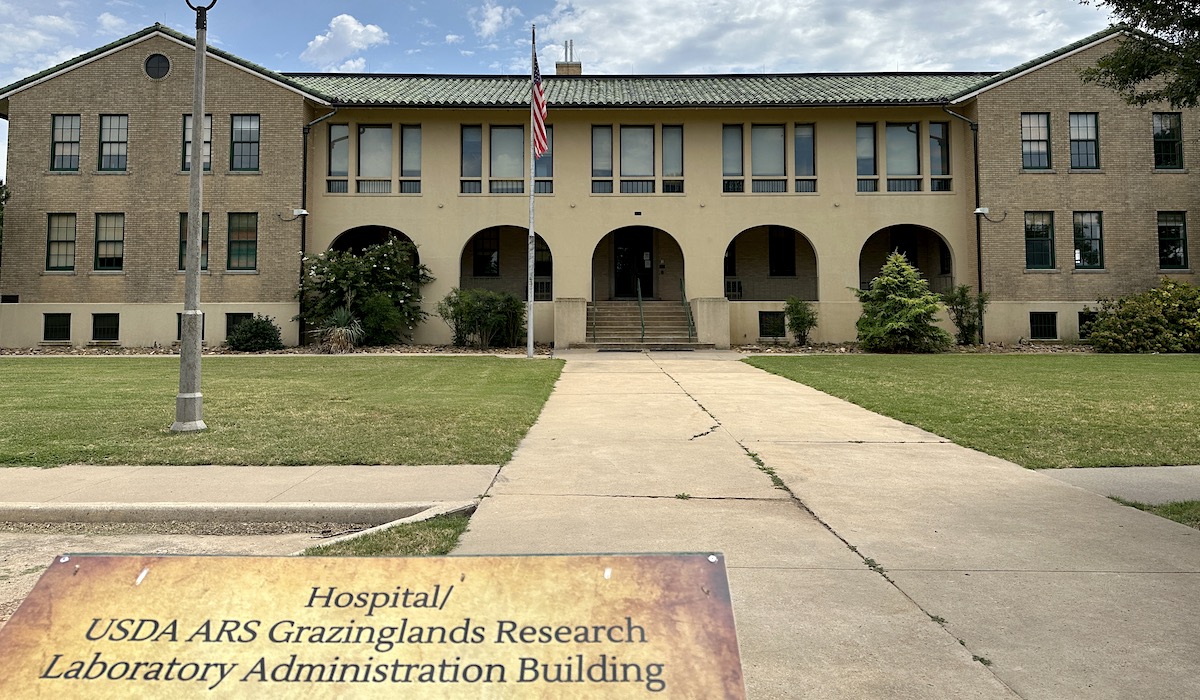

Since taking the land in the late 1800s, the federal government has used Fort Reno to fight the American Indian Wars, house fascist prisoners of war, research climate change, advance agriculture and even breed baboons (until violations of the Animal Welfare Act surfaced). Fort Reno’s U.S. Department of Agriculture facility was slotted for closure in the 1990s but personally saved by one of Oklahoma’s U.S. senators in a move that made national news.

With both the United States and the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes claiming ownership, development of both the land and the substantial oil reserves underneath has become extremely difficult. Passage of the language in the 2024 farm bill would prevent the executive branch from returning the land to the tribes — a move the current U.S. Secretary of Agriculture appears to support — without an act of Congress, functionally kicking the dispute over ownership further down its dusty road until Congress finds the will to resolve it.

‘It’s always been a political football’

Since at least 1908, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes have sought the return of the federal lands making up Fort Reno. After the military base closed and the land transferred to the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the 1940s, Congress has debated returning the land to the tribes, with the House of Representatives passing two bills that failed in the Senate when an Oregon senator opposed the measures because potential oil reserves had been discovered below ground.

In the 21st century, Congress has created additional significant barriers to the land’s return, and the controversial language in this year’s farm bill draft aims to make one of those temporary barriers permanent.

U.S. Rep. Frank Lucas (R-OK3), the current chairman of the House Science Committee, has contributed to writing every farm bill since 1996. He has also opposed the return of Fort Reno to the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes since at least 1995, according to The Oklahoman.

After the retirement of the late U.S. Sen. Jim Inhofe’s in 2022, Lucas became the dean, or the longest serving member, of Oklahoma’s federal delegation. First elected in 1994 to Oklahoma’s now-defunct 6th district, Lucas “worked directly” on the current farm bill proposal’s component regarding Fort Reno, The Hill reported in August.

“It is a parochial issue specific to Oklahoma’s 3rd Congressional District, therefore the committee worked directly with former House Committee on Agriculture Chairman Lucas, who represents the facility, when drafting this provision,” said Ben Goldey, communications director for Rep. Glenn Thompson’s (R-PA15).

Lucas has strongly advocated for the U.S. Department of Agriculture to continue operating the Oklahoma and Central Plains Agricultural Research Center, which is located on the Fort Reno land claim. Asked to discuss the situation, his office provided a statement from the congressman that called it “one of the crown jewels of our nation’s agricultural research facilities.”

“The center’s mission to improve crop- and pasture-based livestock production systems is made possible by the large swath of pristine prairie that the center is located on. This allows for unique research into livestock systems and plant germplasms that occur throughout the region,” Lucas said in the statement. “The fact is, this type of research can only be done in El Reno, and it benefits all communities in Oklahoma and across the Central Plains.”

The title to the land at Fort Reno has held a cloud for decades, and Lucas’ proposed Section 7401 in the farm bill would move neither the United States nor the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes closer to a clear title that could allow for production of the land’s significant petroleum reserves. (Cheyenne and Arapaho ordinances establish a 7.085 percent gross production or “severance” tax applicable to petroleum production on tribal land, a right of the sovereign nation that was litigated heavily in the 1980s and 1990s.)

“I really don’t see why they don’t just turn those minerals back to the tribe,” Wassana said. “You know, if they’re worried about the surface just to do research, then I don’t see what the problem is to say, ‘OK, tribe, here’s your minerals,’ and then the tribe can have resources to develop.”

The issue has long frustrated Wassana, who in 2021 became the tribes’ first governor ever to be elected to a second term.

“It’s always been a political football to keep it away from the tribe,” Wassana said of Fort Reno. “Just like when they put the monkey research out there. Why did you do that?”

Wassana was referring to the baboon breeding and research facility established at Fort Reno in the late 1990s. Eventually operated by the University of Oklahoma, the baboon breeding program involved observational studies of the animals, which were also distributed to medical research labs around the country for vaccine testing and other research owing to the similarities between baboon and human immune systems. In 2015, a rash of deaths among the 300-plus baboons housed at Fort Reno combined with repeated violations of the Animal Welfare Act spurred OU to wind down the program, which it did in 2018.

Baboons can be particularly vicious animals, and the baboon breeding program’s establishment at Fort Reno also bred greater resentment about how federal officials and Oklahoma leaders were justifying their opposition to returning the historic Cheyenne and Arapaho land.

“When the research station was being shut down due to duplication and budget constraints, they found another use, and it was to put a [baboon] research station at an ag research station,” Wassana said.

‘A vexing, difficult issue’

In Congress, the “farm bill” is drafted every five years as an omnibus measure that sets much of the legal framework for U.S. agriculture and food policy. The 2018 version was extended through the 2024 federal fiscal year, which concludes Sept. 30. With the new proposal caught in a fight over SNAP benefits and concerns that it would increase deficit spending by $33 billion, Congress could ultimately extend the 2018 version again.

Asked about the potential effect of the draft farm bill on Fort Reno, U.S. Sen. James Lankford said in an interview that he had not seen the specific language in this year’s proposal, but he has “tracked that issue, obviously, for a long time.”

“I have to say that’s a vexing, difficult issue,” said Lankford (R-OK). “There’s no easy answer on it, because we want to be able to honor the tribal agreements in the treaties that were made in the past. We’re going to do that, both legally and morally. We need to be able to do that, but it’s also that use (of the facility) continues. (…) Is that still actually being used enough that (it) is justifiable on that? And there’s no simple answer on that one.”

Lankford also said there are unresolved legal questions around the status of the land.

“It’s been the concern at some point that (if) it’s not fully used by the federal government, does that (land) actually get returned?” Lankford said. “And so that question still hangs out there unresolved.”

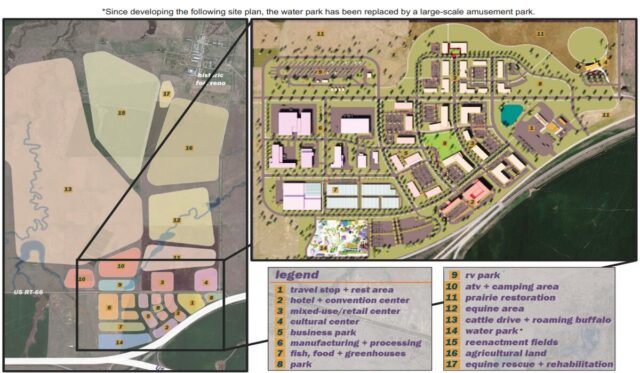

Underscoring their argument that the 9,500 acres in question could have greater economic potential if it were returned to the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, Wassana and other leaders have proposed developing the area south of the USDA facility to Interstate 40. The proposal’s components include:

- A travel stop,

- A water park,

- A hotel and convention center,

- A camping area,

- Business and manufacturing zones, and

- Reserving broad swaths of the land for prairie restoration and agriculture.

According to Hunden Partners, the “destination real estate development” consultant hired by the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, the overall proposal could induce $27 billion in net-new spending over a 30-year period.

At a National Congress of American Indians event June 5, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack expressed support for “working collaboratively to get these lands restored” and criticized the current version of the farm bill for hampering efforts to restore tribal lands.

“We also need to push back on the notion that we should be restricted from [returning lands],” Vilsack said. “The current House version of the farm bill that passed through the agricultural committee basically contains a provision that says under no circumstances should you do this. We’re obviously going to have to push back hard on that notion, which I am prepared to do.”

Vilsack also expressed support for keeping the federal research facility at Fort Reno open, while simultaneously returning most of the land to the tribes.

“I think there’s an opportunity to figure out a way this could work for both,” he said. “There’s important research being done there. Is there a way in which the land can be restored but research continue? I think there probably is a way.”

Fort Reno: Frontier base to World War II POW camp

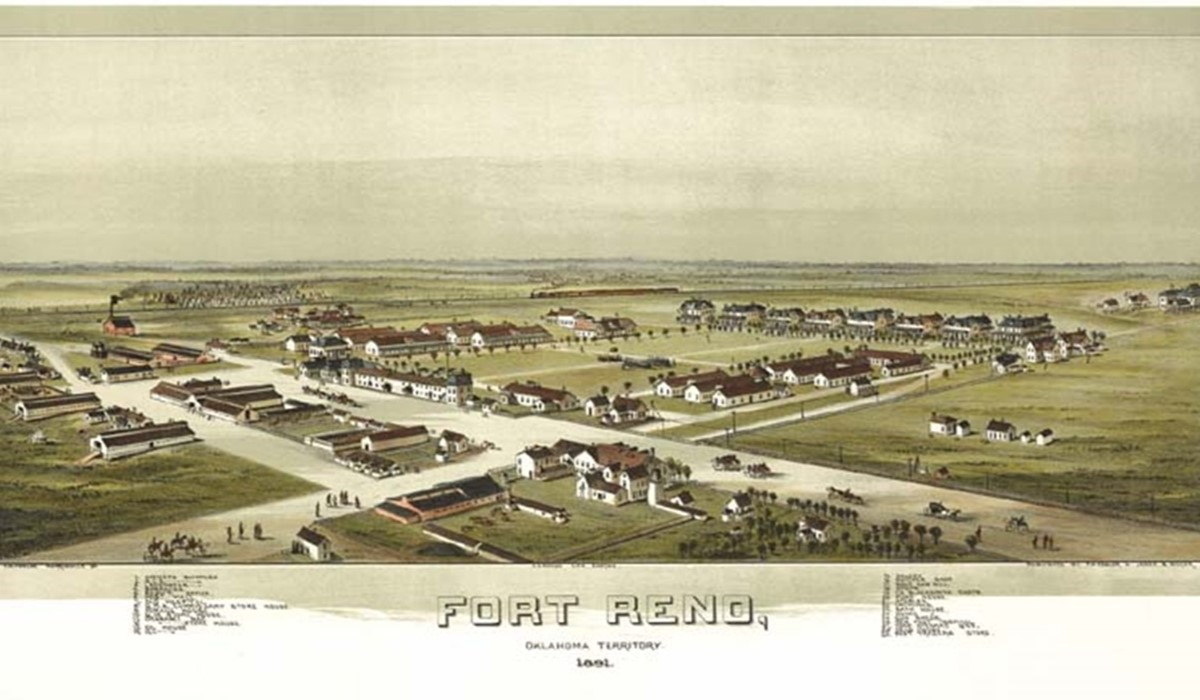

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes were two separate nations in the central plains before signing a treaty with the United States in 1867 requiring their move to Kansas. Two years later and before moving to the Kansas reservation, the tribes negotiated for a 5.4-million-acre reservation in then-Indian Territory that was granted by President Ulysses S. Grant via executive order.

Soon after, however, the federal government established a military camp there and officially took 9,500 acres from the tribes in 1883 to designate the area as Fort Reno for use in the American Indian Wars. The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes expected the fort’s lands to be returned after the area stopped being used as a military base. The fort remained active through World War II, serving as one of several locations in Oklahoma used to house German prisoners of war.

In 1948, the land of Fort Reno was transferred from the military to the USDA, and the transfer prompted debate in Congress, with two proposals to return the land to the tribes. Both passed in the House of Representatives in 1949 and 1952 before failing in the Senate.

In 1965, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes settled all land claims accrued against the United States before Aug. 13, 1946, in the Indian Claims Commission. The settlement did not include payment for the Fort Reno lands because the Fort Reno claim originated in 1948 after the commission’s creation date.

In 1972, the Quiet Title Act was enacted by Congress, waiving the United States’ sovereign immunity for quiet title claims and allowing parties to sue the federal government over competing land claims. Key to the Cheyenne and Arapaho’s situation, the act contains a 12-year statute of limitations that bars the tribes’ 1948 claim against USDA from being pursued in court.

While most landowners could file a quiet title action asking a court to resolve the dispute, it is more complicated for tribal governments with older claims. The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes did file a claim, but it was dismissed by the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals under the Quiet Title Act in 2009 without resolving the clouded title.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

A redundant facility saved by a senator — filled with baboons

By 1995, the USDA facility at Fort Reno was on the verge of closing after being listed as redundant. However, then-U.S. Sen. Don Nickles (R-OK) saved the facility by insisting on including funding for it in the national budget even after his efforts to construct a military cemetery on the property were thwarted by tribal opposition. Within a couple of years, the baboon breeding and research program began, among other gnashing of teeth.

During President Bill Clinton’s 1996 reelection campaign, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes made headlines for donating $107,000 to the Democratic National Committee in hopes of winning Clinton’s support for the return of Fort Reno land.

However, the donation primarily served to further controversy about the issue, and it became the subject of a U.S. Senate inquiry into political fundraising. Eventually, tribal leaders sent a “cigar store wooden Indian” to the White House in 1999 when no progress had been made regarding Fort Reno. That same year, the U.S. Department of the Interior published a memo acknowledging the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes’ claim to the land as legitimate and noting that the tribes were never compensated.

The years following the tribes’ foray into national politics included investigations and the prosecution of several tribal leaders on various charges, according to a letter sent by Cheyenne and Arapaho Legislator Patrick Spottedwolf to then-Attorney General Eric Holder in 2010.

“I believe those prosecutions were in relationship to our congressional delegation and its efforts to see mineral rights developed on Fort Reno lands,” Spottedwolf wrote. “As you can see, the efforts to recover Fort Reno and subsequent convictions have come on the heels of some pretty high-profile acquittals for the tribal officials who undertook the task to recover Fort Reno.”

Spottedwolf alleged that Cheyenne and Arapaho tribal officials who faced retaliatory investigation in the 1990s and 2000s included:

- Chairwoman Juanita Learned, whose tribal membership was investigated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1986, after she clashed with Nickles over Fort Reno. Learned was also investigated by the FBI in 1990 after she advocated for a tribal “land run” of the Fort Reno lands;

- Chairwoman Viola Hatch, who was was indicted in 1994 and acquitted in 1996 for improperly using travel funds after protesting Nickles’ proposal for a national cemetery at Fort Reno;

- Chairman Charles Surveyor, who was investigated in 1996 for approving the DNC donation in support of Clinton’s campaign;

- Chairman James Pedro, who was indicted in 1999 after placing an ad critical of Nickles in the Washington-based publication Roll Call;

- Chairman Robert Taylor, who was indicted in 2002 after having approved the donation to the Clinton campaign and authorizing an ad campaign against Nickles; and

- Chairman Bill Blind, who was indicted in 2004 and later convicted after calling U.S. policy toward the tribe “genocide” and advocating that separate land in Colorado be returned to the tribe.

“Although it is clear that some of the prosecutions were perfectly justified, it also appears that several of them were connected to the tribes’ attempts to recover Fort Reno,” Spottedwolf wrote.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

‘One day it will come back to the tribes’

In 2002, Congress included a section in that year’s farm bill to bar the transfer of federal lands at Fort Reno before Dec. 31, 2007. The section was included in response to the Clinton scandal a decade prior and to prevent a presidential administration from returning the land without congressional approval, according to a congressional staffer familiar with the legislative history.

In 2008, an amendment barred the transfer of Fort Reno lands for another five years. The five-year ban was later extended into a 10-year ban and later a 15-year ban on transferring the land out of federal hands.

Despite decades of setbacks, Wassana said he remains confident the tribes will eventually be successful in getting Fort Reno returned to them, but he acknowledged that Lucas’ language would be an enormous hurdle if the current version of the farm bill becomes law.

“One day it will come back to the tribes, and I really feel that, and I believe it. It will be done,” Wassana said. “They can keep it away from the tribes for a long time, but somebody is going to step up and do the right thing one of these days.”

Review the tribes’ Fort Reno development proposal