The ACLU of Oklahoma filed lawsuit this afternoon challenging the residency eligibility of new Oklahoma Supreme Court Justice Patrick Wyrick.

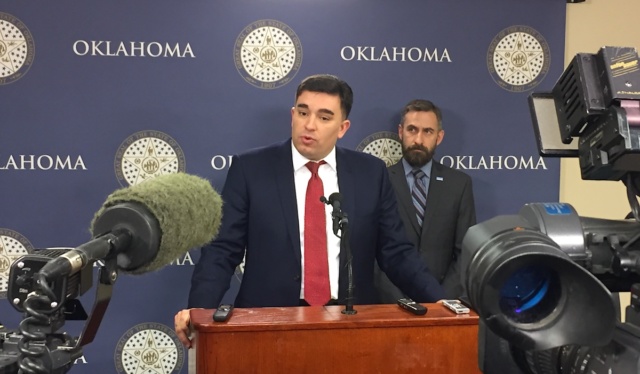

“His claim to residency required by the constitution is simply not true or accurate, and as such, we are asking the Supreme Court to take up the issue of whether or not he can actually be seated as a justice of that court,” ACLU legal director Brady Henderson said at a press conference today. “To our knowledge, this is unprecedented. We haven’t seen it before in Oklahoma.”

Wyrick was appointed to the state’s highest court last week by Gov. Mary Fallin, and he was sworn in soon thereafter. Henderson and Ryan Kiesel, executive director of ACLU, said they both know Wyrick personally and are not challenging his “fitness” to serve. Instead, they said their focus is on his constitutionally mandated eligibility to fill the seat that represents southeastern Oklahoma.

Article 7, Section 2 of the Oklahoma Constitution states any justice “shall have been a qualified elector in the district for at least one year immediately prior to the date of filing or appointment.”

“What we have seen in this appointment of Justice Wyrick is that the right of the people in the second supreme court district to have representation has not been filled,” said Kiesel. “It’s incredibly important that the people of Oklahoma can look at the judicial branch and know that their integrity is well-placed.”

Fallin’s office has stood by its appointment of Wyrick, issuing a statement to media explaining the constitutionally prescribed selection process.

“Section 3(e) of Article VII-B of the Oklahoma Constitution provides that ‘The (Judicial Nominating) Commission shall have jurisdiction to determine whether the qualifications of nominees to hold Judicial Office have been met…’,” Fallin’s general counsel, Jennifer Chance, said in a press statement. “The commission exercised its constitutional authority and the governor accordingly selected Patrick Wyrick to fill the vacant position on the Oklahoma Supreme Court.”

But the ACLU’s case, filed on behalf of plaintiffs Susan Spencer and Cheri Chandler, who are residents of the second supreme court district, does not focus on Fallin’s selection or the JNC’s nomination process.

“The Judicial Nominating Commission here obviously missed his real residency. We don’t know why. It’s a reality of that commission,” Henderson said. “But even when those things happen, the state constitution and statutes provide a clear way to deal with it. A commission’s failure to notice something doesn’t change the state constitution. They don’t have the ability to waive the constitutional rights of state citizens.”

Wyrick was one of three finalists put forward to Fallin by the Judicial Nominating Commission, a nonpartisan body intended to ensure meritorious selection of qualified judges.

RELATED

Residency question could dog Okla. Supreme Court appointee Patrick Wyrick by William W. Savage III

People of varying degrees of closeness to the Fallin administration have suggested that the JNC deserves substantial criticism if Wyrick’s eligibility were to become questioned. The commission sent the names of Wyrick, Bryan County District Judge Mark Campbell and LeFlore County Judge Jonathan Sullivan to Fallin as qualified applicants, and the extent to which the governor or her staff would then vet those finalists’ eligibility or qualifications is unclear.

The commission typically does not discuss its activities with media.

But Henderson laid out evidence of Wyrick’s residency in the OKC metro area based upon county records and voting history.

“His claim to residency as required by the Oklahoma Constitution is simply not true or accurate,” Henderson said of Wyrick today. “He does every single prominent exercise of residency not in Atoka County, where he swore to be from for purposes of the Judicial Nominating Commission, but rather in Cleveland County.”

Kiesel called arguments that Wyrick could be eligible to serve from multiple court districts “the Schrödinger’s Cat of qualified elector theory.”

“Even assuming that can happen, we have a mountain of evidence that he is a resident of places other than Atoka and very little evidence that he is a resident of Atoka,” Kiesel said.

As a result of the lawsuit, Henderson said Wyrick will have to determine whether he wants to contest the claims made against him. Henderson said Wyrick could choose to represent himself or hire outside counsel.

He also said Supreme Court justices could recuse themselves if they believe a conflict of interest exists, but he said he believes the ACLU’s case doesn’t cause those types of conflicts because the matter has nothing to do with Wyrick’s time on the bench.

‘Materially inconsistent’ answers on Wyrick’s application

Monday, NonDoc published an editorial examining Wyrick’s application for the Supreme Court post. On that application, Wyrick responded to separate questions about his residency with contradictory answers.

Wyrick Wrote that his residency had been in southeastern Oklahoma’s district two “since birth,” but he also listed the communities of Broken Arrow, Norman, Moore and Oklahoma City as his places of residency over the past 10 contiguous years.

Kiesel and Henderson noted that their lawsuit does not focus on Wyrick’s “materially inconsistent” application answers, but they noted that more than one prosecutor in the state may have jurisdiction to determine whether Wyrick willfully wrote a falsehood on his application.

“It’s obvious that both of those statements cannot both be true,” Henderson said. “It’s not possible. As a lawyer (…) if a client said, ‘Can I do this? Is it going to be OK?,’ I would say, ‘No, don’t do that.’ For kind-of-obvious reasons.”