(Editor’s note: This story was authored by Jennifer Palmer of Oklahoma Watch and appears here in accordance with the non-profit journalism organization’s republishing terms.)

Participation in advanced-level math and science classes in high school is a strong predictor of success in college, regardless of the grade earned in the class or whether it results in college credit, studies show.

Yet as many as two-thirds of Oklahoma high schools report they don’t offer calculus or physics, leaving swaths of the state devoid of these classroom opportunities, according to data for the 2014-2015 school year, reported by schools to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights.

Calculus and physics aren’t needed for a high school diploma, and schools may offer other high-level math and science courses, such as statistics. But calculus and physics are regarded as key concepts used in many other disciplines. And the classes are essential for entry into well-paying careers in science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM, as well as medicine.

At the least, offering such rigorous courses – or a lack of them – sends a message to students about expectations, some experts say.

“Offering a variety of advanced classes — AP or IB courses, as well as advanced math and science — tells students that the school expects them to complete a rigorous course of study, and believes in their ability to do so,” said Natasha Ushomirsky, K-12 policy director for The Education Trust, a national nonprofit advocacy organization. “Offering no such courses sends a very different message.”

AP, or advanced placement, and IB, or international baccalaureate, are high school classes offering more challenging work than the standard curriculum.

For students whose school doesn’t offer advanced classes, there are alternatives, such as tuition-free community college courses, technology center programs or online classes. But students may be deterred from those by fees, transportation challenges or scheduling complications.

Another option for high school students is concurrent enrollment in college, but administrators at several community colleges say students are not clamoring to enroll in calculus or physics. Of the 1,800 high school students enrolled at Tulsa Community College, just 31 are taking analytic geometry or calculus. Two are in physics.

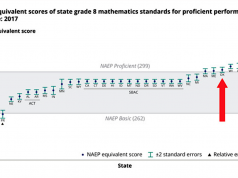

The latest state rankings available from the U.S. Education Department – from the 2011-2012 school year – show that Oklahoma had the third-lowest percentage of schools reporting they offered calculus, with 34 percent, just above Alaska and North Dakota. Oklahoma schools reported the second-lowest percent offering physics, at 36 percent, above only Alaska.

And although Oklahoma reported one of the highest percentages of high school availability of Algebra 1, at 95 percent, that, too, could be interpreted as a sign the state is lagging. To reach calculus by senior year, students should complete Algebra 1 in middle school.

The self-reported data likely contains some discrepancies, such as whether a school counts pre-calculus as a calculus course, and may not capture the full availability of courses in districts that rotate offerings every other year. Additionally, some districts disputed the numbers published by the department. But the data collection is subject to a series of embedded checks to ensure significant data errors are corrected before districts submit, according to the federal Education Department.

Haves and have-nots

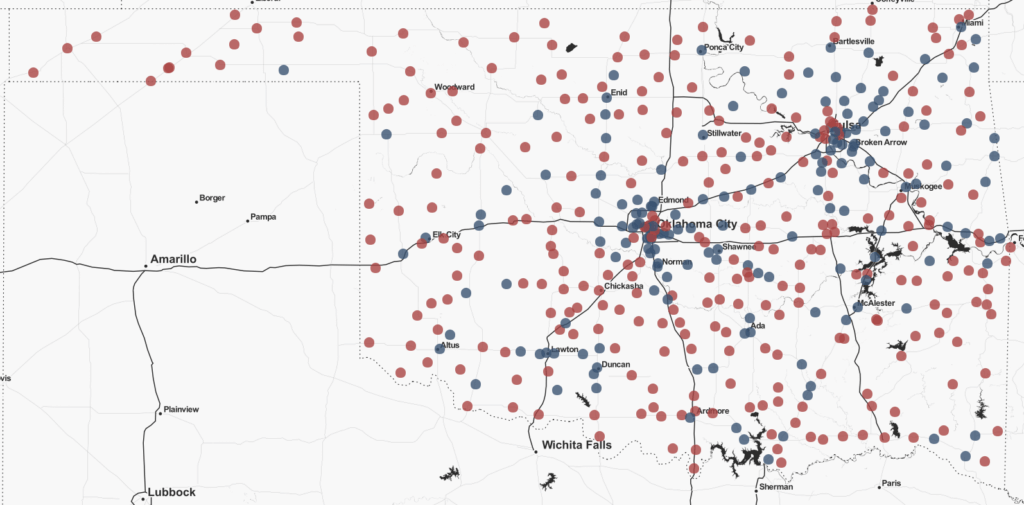

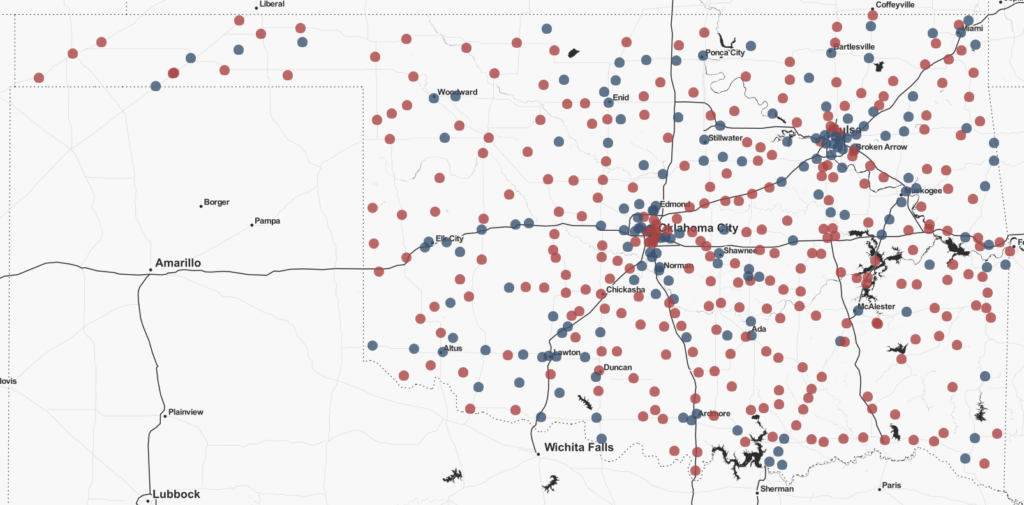

Using federal data from school year 2013-14, Oklahoma Watch mapped all of the state’s high schools, assigning a blue circle to those offering at least one calculus (or physics) course and a red circle to those with none. The data were self-reported by schools to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights. Pre-calculus classes are not included. A sample check of some districts found several discrepancies; district officials said their data was recorded incorrectly. As a result, circles for five schools in Tulsa, Ardmore and Stillwater were changed from red to blue.

Calculus

Physics

Where calculus is (and isn’t)

Oklahoma Watch’s mapping of high schools offering – and not offering – calculus and physics in the 2013-2014 school year shows large areas and many schools with no availability on campus. Dozens of schools that offered one course or the other had relatively few students enrolled in the class.

The math and physics “deserts” are especially evident in southeast, north-central and far northwest Oklahoma, including the Panhandle. But even in midsize and larger cities, scarcities exist.

Interviews with high school principals across the state reveal a wide range of calculus and physics availability, from high schools offering a full suite of math and science classes to those offering the bare minimum for students to graduate.

There are small districts scraping by with one math teacher and medium-sized districts struggling to hire physics or calculus teachers. Oklahoma City and Tulsa public schools offer numerous advanced math and science opportunities at some high schools and one or none at others.

At Plainview High School near Ardmore, 20 percent of the school’s graduating seniors this year are taking calculus – an increase from 2013-14. The 1,500-student district encourages middle school students to take Algebra 1, setting them up for calculus by senior year.

North of Stillwater in Morrison Public Schools, just two of the district’s 570 students are enrolled in calculus, and it’s an online course. The high school offers two STEM classes, but they are electives, not for math or science credit. Physics isn’t offered.

Within the state’s largest urban districts, availability of these classes is unequally distributed. The Office of Civil Rights data collected from schools show calculus was offered at six of Oklahoma City Public Schools’ 10 high schools, and just one offered physics. In Tulsa Public Schools, two of its nine high schools offered calculus and all but two had physics, the data show.

However, the Tulsa district said it actually had more calculus and physics classes than the federal data reflect, attributing the discrepancy to the reporting process. Four of its high schools offered no calculus and only one no physics.

At Booker T. Washington High School, a Tulsa magnet school, for instance, students have access to a full range of advanced math and science classes, including 15 calculus classes and 10 physics classes. Other offerings at the 1,300-student school include 24 AP courses and 41 IB courses.

Three miles away, at McLain High School for Science and Technology, a Tulsa magnet school that, according to the district, emphasizes math and science, there are no physics classes and just one pre-calculus class for 600 students.

Behind the gaps

School administrators say it’s not that they don’t want to offer calculus or physics. They cite a lack of resources, whether the funding to pay a teacher’s salary or the lack of a teacher qualified to teach it.

“Math and science teachers are hard to get. We’re lucky to find somebody that’s certified to come to our school, because they can usually find a bigger school that pays a little better,” said Brent Drury, principal of Olustee High School, which has 159 students and one math teacher this year. The southwestern Oklahoma school doesn’t offer calculus, and alternates between Algebra 3 and trigonometry each year.

A Tulsa Public Schools spokeswoman said the district is committed to making course offerings more equitable across the district. Oklahoma City, too, says it is working to increase the rigor of its classes.

“We’ve spent a lot of our energy focusing on the students that were behind. And we didn’t focus as much energy on the students that were prepared and able to do more rigorous coursework,” said Brad Herzer, the Oklahoma City Public Schools’ interim curriculum director of PK-12 schools. “There’s been a shift. We need to focus on both groups.”

Finding a teacher to teach calculus or physics is a hurdle many schools that want to offer the courses struggle to overcome.

When the physics teacher at Cushing High School — a former astronaut — retired last year, Principal Jim Lauerman couldn’t find a replacement. So the course was cut from the school’s offerings, and some of the students interested in physics ended up in calculus instead.

“It hurts,” Lauerman said. “In some of the lower classes, you could find somebody to wing it, but not in physics or calc. That’s not something you can wing.”

Oklahoma is already facing a teacher shortage, with a record 1,082 emergency certified teachers in classrooms around the state. Competition for advanced math and science teachers is stiff, administrators say, and includes not just other school districts but private sector jobs, too.

‘Path of least resistance’

The need for workers skilled in math and science has been well documented, especially in Oklahoma where jobs in aerospace and oil and gas are plentiful when the economy is good.

A new report by testing company ACT found Oklahoma students’ interest in STEM careers is on par with the national average. But students here fall far short of being prepared for success in STEM fields.

Of Oklahoma seniors who took the ACT test in 2016, half were interested in STEM but only 17 percent of those interested students met benchmarks showing preparedness for a STEM career.

Plainview High School Principal Brian Nickel says students need more than access to advanced courses — sometimes they need a little push. Of the school’s 100 seniors, 20 are taking AP calculus.

There are always a handful of students propelled by a desire to be valedictorian or attend an Ivy League school. Many others are intelligent but not as motivated, he said.

“Their natural inclination is to take the path of least resistance,” Nickel said. “We have to work really hard to tell our kids and reinforce that putting yourself through the grind … is worth it.”