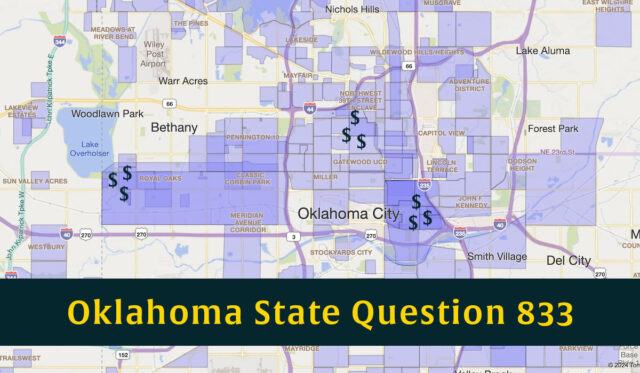

A proposal authorizing the creation of new taxing districts that could help cities finance infrastructure improvements — if all the property owners within the district agree — will be decided by voters taking part in Oklahoma’s Nov. 5 general election.

State Question 833, which the Legislature voted to place on the ballot, would amend the Oklahoma Constitution to allow cities to create public infrastructure districts that can be used to pay for roads, sidewalks and parks, as well as water and sewer improvements.

Proponents say the measure could help developers with the cost of building housing subdivisions, especially in cities that may not have the bonding capacity to help pay those costs.

Opponents say the proposal is vague by not defining public infrastructure and lacks sufficient safeguards.

State Question 833 needs a simple majority to pass. If it passes, it won’t take effect until at least next year because lawmakers plan to fill in details with statutory guidelines during the upcoming session, which begins Feb. 3.

For that reason, the Oklahoma Municipal League is staying out of the political fray, said Leslie Blair, director of legislative affairs and communications.

“We have not taken a position on 833 in any way, either opposing it or supporting it, but we’re aware of it and we’ll be watching to see what happens,” Blair said. “If it passes, we will be involved in conversations moving forward about either guardrails to put in place and definitions. So, it’s something we’re watching.”

Sen. John Haste (R-Broken Arrow) wrote Senate Joint Resolution 16, which designated SQ 833 for a vote of the people. SJR 16 easily passed both chambers: 38 to 7 in the Senate and 66 to 27 in the House of Representatives. Haste said lawmakers this past session considered drafting legislation that would have included regulations and other details.

“But the decision was not to do it, get into all the nitty gritty, until it actually passed,” Haste said in an interview.

If approved by voters, SQ 833 would allow 100 percent of surface property owners in a portion of a municipality to petition to the city to create a PID to finance infrastructure in that area. If approved by a city council or city commission, the PID would be able to issue bonds to finance infrastructure projects in the area. The bonds would be repaid through a property tax assessment of up to 10 mills on the properties in the PID. (A “mill” equals $1 in tax for every $1,000 in taxable value of a property.)

“We did put some things in there, like a maximum 10 mill, because this is in place in Missouri, Texas, Utah, Colorado, where they used these,” Haste said. “And we felt like that was one of the safeguards or guardrails we wanted to put in place, that the maximum you could do would be 10 mills.”

Haste said Oklahoma has a housing shortage across the state. One of the most significant barriers to new homes being built is the need for including critical infrastructure. PIDs would be a help to cities in financing the required infrastructure, he said.

“It’s another tool in the tool belt to help the state as we’re growing — to be able to use it for housing, but it also is something that gives a choice,” Haste said. “It will help us as we, like I say, grow as a state, but it very much gives you options. And like I say, if somebody doesn’t want to participate in it, if they don’t have to, and if they want to, there’s an opportunity.”

While SQ 833 may sound promising, voters should be cautious, said Rep. Andy Fugate (D-OKC), who has posted a video on Facebook criticizing the measure.

“It proposes a new taxation district and (authorizes) a new property tax to fund public infrastructure inside that district. Unfortunately, the state question doesn’t define public infrastructure,” Fugate says in his video. “Without guardrails, this state question is an easy grift that profits a handful at the expense of the rest of us. Imagine that.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

How PIDs would work

As proposed, a PID could be used by one or multiple developers on a tract of land within a municipality who want to create a property tax to cover bonds for infrastructure projects on that tract of land.

“That could be roads. It could be trails. It could be sidewalks, water, wastewater, that kind of stuff,” Haste said. “Well, particularly, in cities that have a lot of growth, they may or may not have the bonding capacity to help with this. So, what they can do is go to the city. First of all, it has to be in an incorporated area. So, if it’s not incorporated, it can’t be used.”

The developer or developers would ask the city to set up a PID that would allow for bonding.

“Then they’d have to submit a variety of documents and so forth in support of this, as well as the governing documents related to the bond and so forth,” Haste said. “And if the city approves it and allows them to move forward, then what would happen, you go in to buy a lot within that development to build a house. (…) So, here they will tell you that, OK, now we have this bond. And so, you will be assessed so many mills.”

RELATED

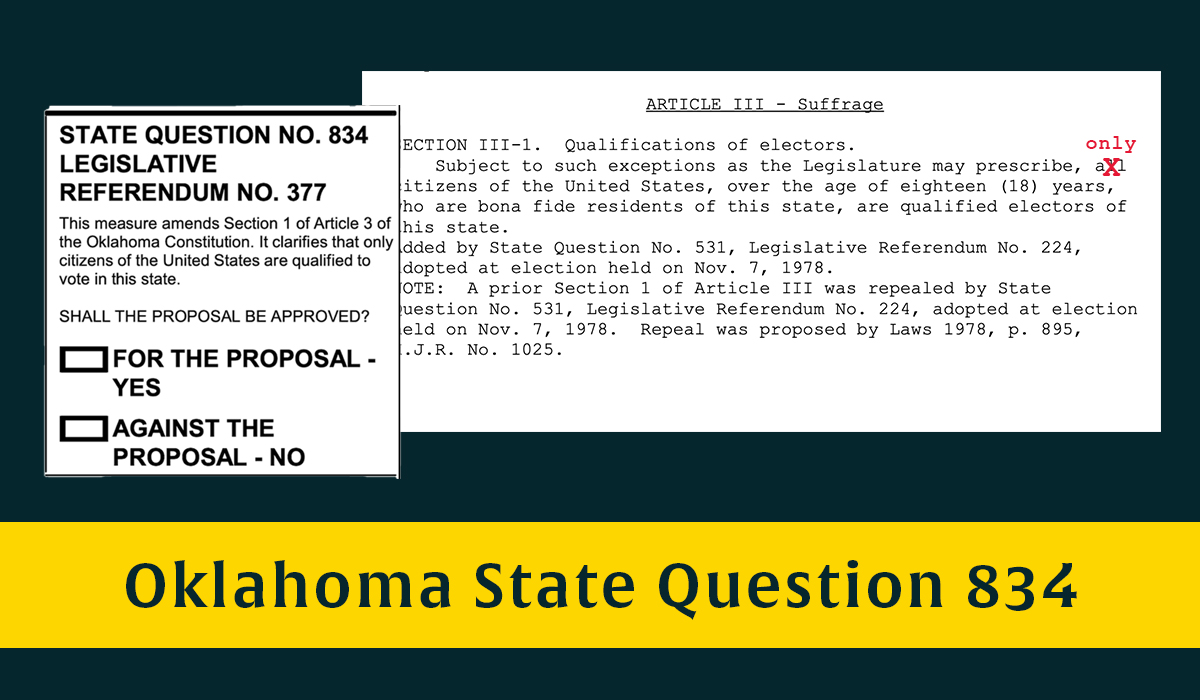

State Question 834: One-word change debated as noncitizens already ineligible to vote by Michael McNutt

Haste said a 10-mill assessment on a $300,000 house would amount to about $300 a year.

“Now you’re told this, and you say, ‘Well, no, I’m not interested in paying that,'” Haste said, noting that a prospective lot owner could simply decide not to purchase the lot.

Property owners outside the PID would not have their property tax assessments affected, he said.

“It’s just those that are getting the benefit of the amenities, the ones that benefit would be the ones that are paying it, not anyone else,” Haste said.

PIDs could be used also in existing developments, he said.

“Maybe wastewater or water, something needs to be replaced, or there’s roads or so forth where the development is responsible for,” Haste said. “Then what they can do then is potentially bond to pay for that. But in that case, they would have to get 100 percent buy-in by every surface owner within that development. So even one could say, ‘No, I do not want to do that,’ and it would not happen. So, that’s when I talk about choice. You have to have the choice to participate or not.”

A PID would not work in a subdivision where the city is responsible for such things as streets, water, wastewater and sidewalks, he said.

“Where I do see it, though, is you’re in a development, and the development is responsible for those roads, or those sidewalks, or whatever, or they want to add stuff, then that’s where I could see one being done because they’re going to have to pay for it anyway,” Haste said. “And so, by being able to bond it makes it a little more palatable for them. It does not go against the city bonding capacity, and the city is not guaranteeing payment.”

Trusting legislators ‘on a promise to do things right’

In an interview, Fugate said it is easy to for voters misinterpret State Question 833 to assume it creates guardrails that don’t actually exist, such as presume that “public improvements” mean infrastructure for the general public.

“That’s just not the case,” he said. “A developer could use this to build amenities — you know, a park, a swimming pool, a golf course — inside an exclusive community. And while those meet the definition of a ‘public improvement,’ they’re not available to the general public, per se,” Fugate said. “It would be trivial for them to do that if a developer purchases the entire area that would be part of that public infrastructure district. That means the petition comes from a single individual.”

That single developer, or one person, would still need to get approval from a city council or commission.

“But that city council might be swayed by the argument that they’re going to have this high-end exclusive community as a crown jewel for the greater community,” Fugate said. “And so, they would then sign off on that.”

Fugate said another concern people have about SQ 833 is that those living in a PID — homeowners paying more in property taxes than other city residents — might be less inclined to vote for other property tax proposals, such as school district bond issues.

Beyond that, Fugate said voters should be skeptical of SQ 833 since it means the Legislature would be in the details.

“Voters don’t trust the Legislature with their money,” he said. “And they certainly don’t trust legislators on a promise to do things right.”

Fugate said he does not think PIDs would offer much help in developing housing for low-income residents. It seems impractical that low-income residents would move into a development or subdivision that has a higher property tax, he said.

“If we’re really interested in developing low-income housing opportunities for people, we need to be looking at two things,” he said. “No. 1, we ought to be looking at additional tax credits that could be used to build that. And we ought to be looking at ways to prevent corporate buying that is driving up the cost of housing today.”