When U.S. Grant students filed into their auditorium Thursday morning for a guest speaker, some were not sure who they were preparing to see.

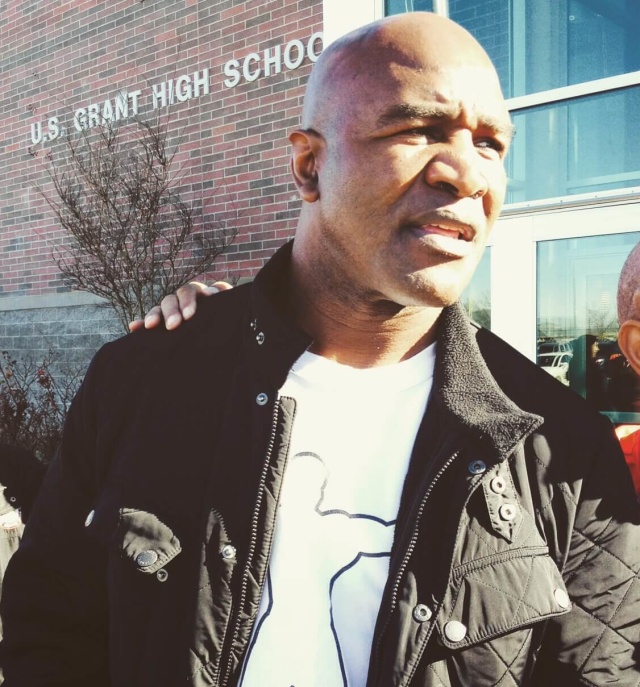

Backstage, five-time world heavyweight boxing champion Evander Holyfield smiled boyishly at Grant principal Greg Frederick: “They are playing a video of me!?”

The Real Deal, known for legendary bouts with Mike Tyson (in 1996, “the upset of the year”) and gladiator-like tenacity, had been whisked into the school and up to the auditorium’s curtain by members of the Oklahoma City Police Department’s PAL program — the Police Athletic League.

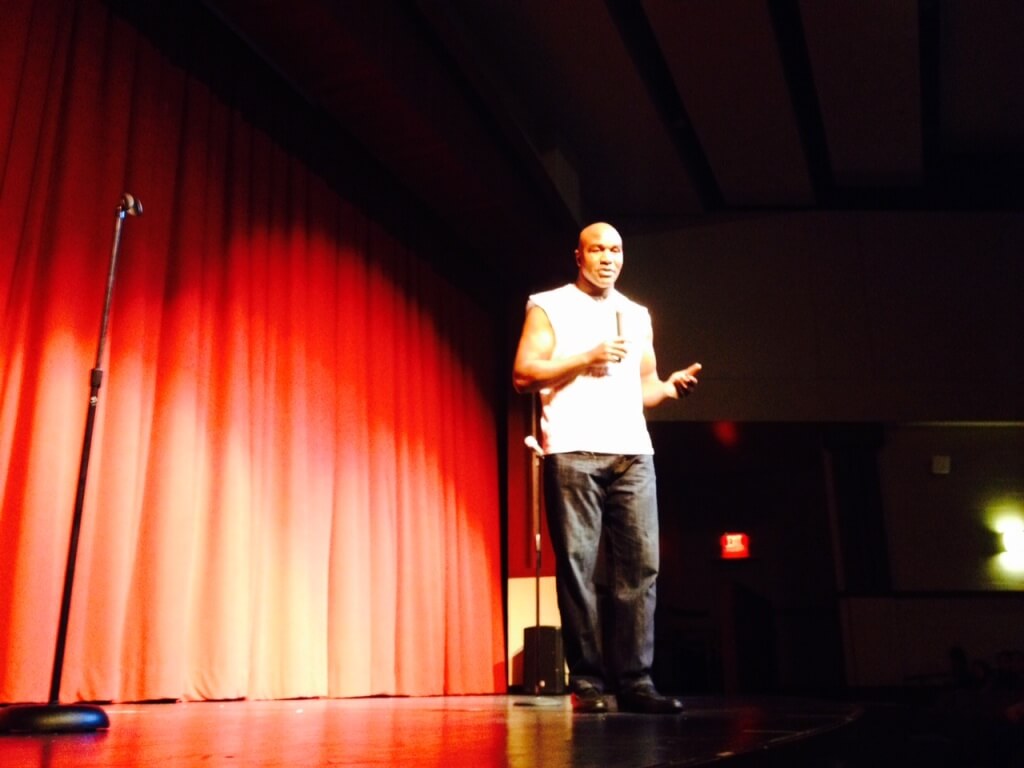

The champ stood in his white sleeveless t-shirt waiting for the intro to wrap. He shadowboxed lightly then stopped. He stiffened his forearms, held them out to the side, and spun them in little revolutions. Then he took to the stage.

“Son, do your very best,” Holyfield recalled his own mentor as saying. “You don’t quit. That’s how boxing started.”

The spokesperson for the national Police Athletic League, Holyfield was in OKC to inspire youth Thursday morning and help raise money for PAL’s annual fight-night fundraiser Thursday evening. In essence, the goals were the same: support kids.

‘Everyone who is successful has a support group’

Norman Mailer said heavyweight boxers are like God’s big toe because there is nothing by which to measure them. When one employs a softer touch to motivate young strangers, however, it’s far easier to calculate his humanity.

Holyfield’s speech Thursday to about 1,000 Grant Generals featured discussions of his legacy and bits of autobiography for youths who he said are younger versions of himself: thirsty for confidence.

Follow NonDoc:

“I became who I am because this old man, Carter Morgan, said ‘Do you know you could be like Muhammad Ali?’ I believed him,” Holyfield told the audience.

Holyfield met Morgan, his trainer at age 21 at a Boys and Girl’s Club in Atlanta. His athletics journey had begun there when he was six, entering the club with friends. It cost a quarter for him because he wasn’t a member, Holyfield recalled. The woman at the door lent him the coin after seeing he would have a long walk home.

Holyfield reminded U.S. Grant students that the woman was white. His own mom, who had a sixth-grade education, insisted he not be prejudiced.

“I really think everyone who is successful has a support group,” Holyfield said. “How many choose their parents? Nobody chooses their skin color. You have to deal with the parents you have. I got three whoopins a day and didn’t know if I was bad or she was. But she stayed on me because she wanted me to better than she was.”

The shy kid among his brothers, Holyfield said kids made fun of him at school for not speaking very well. Later, he worked three jobs for about $8,000 annually. But these were all things that happened, he said, noting the importance of adjusting one’s attitude for all the struggles in life.

Hearing a talk is easy — living is harder

Attitude and prejudice appeared to be interesting topics for Holyfield’s audience Thursday, a crop of kids who must navigate high school along fault lines that remain racially charged.

At one point after Holyfield’s speech, a student yelled, “Black Lives Matter!” Lt. Jermaine Johnson of the PAL program stepped to the mic and said he heard what the student said, but that we should be saying “All Lives Matter.”

The exchange seemed like a reminder — like a tremor of nature — that hearing a talk is easy, but living as a young person of color can be harder.

Out in the audience, two Grant juniors, Mahogany Coston and Erica Spivey, didn’t know what was going on before Holyfield appeared on stage. They had missed school the day before.

Upon hearing Holyfield was the speaker, Coston, wearing a Straight Outta U.S. Grant red hoodie, said, “The fighter? Really?”

Coston is involved in a few sports, but was kicked off the basketball team for having an attitude problem, she said. Spivey said she felt their ethnicity, black, is not as represented at Grant as it may be at other schools like Centennial and Star Spencer, for example. However, Coston said she likes her math teacher, and both girls are on the Step team.

PAL police, Off Duty, and in the Community

Started in 1991 as a crime-prevention program approved by the Oklahoma City Council, PAL is primarily focused on keeping at-risk youth out of trouble through athletics. PAL employs 4 officers. Each works with five elementary schools a piece and one middle school. The district operates about 70 schools total.

Master Sgt. Devon Sawyer of PAL said it would be nice to have more officers, but that it’s difficult owing to the shortage of officers already on the streets. Ten officers applied for the last PAL position, officials said.

PAL’s latest hire is former UFC fighter Sgt. Matt Grice. He and his colleagues work with PE coaches and civilian volunteers to run volleyball tournaments, martial arts classes and other sporting competitions. At PAL headquarters, a retired captain offers a mentoring program.

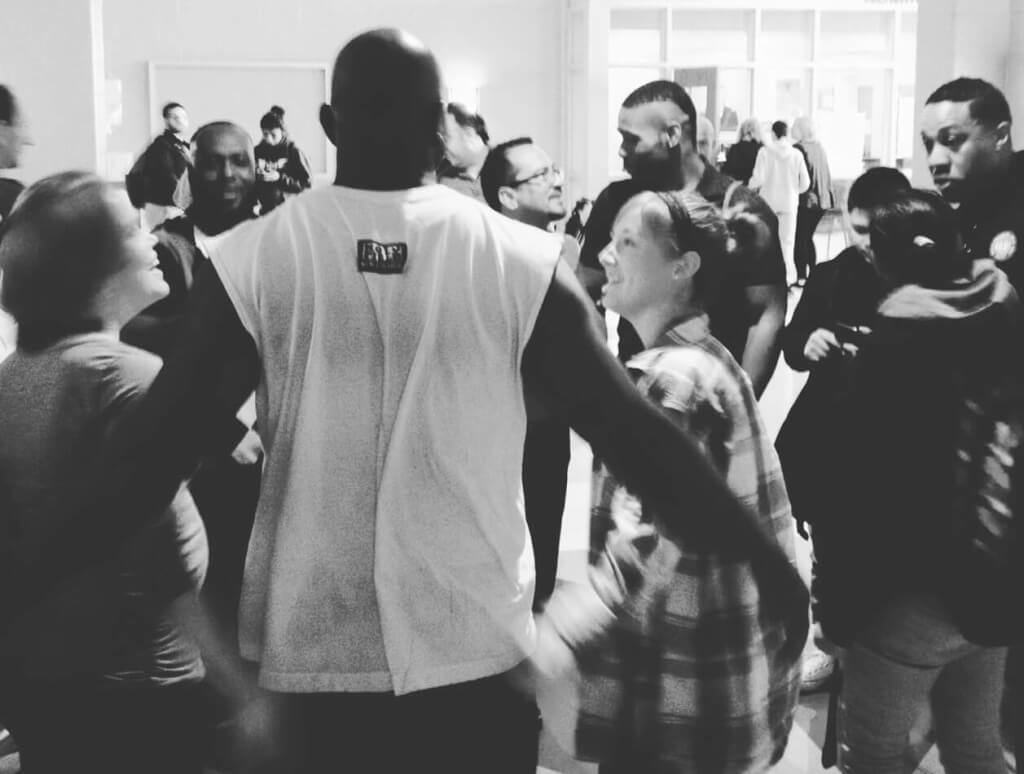

“It’s interesting to see the kids’ reaction when we tell them that we are mothers, that we have children,” Sawyer said. “And it’s like, they see a police officer, and they think we are this RoboCop or something like that. So we try to bring that, ‘We are a person, we have families, we have concerns, we shop at the store.’ The kids, they see us as what they show on TV or what people around them tell them about us. And so we try to let them see the real thing.”

Sawyer said working at PAL offers relief from getting jaded while working patrol, running into the worst of the worst and putting kids in jail. Through PAL, she said officers get to have more conversations.

“It’s nice to be where I am now, and to work with the kids that want to do good, want to improve,” Sawyer said. “Hopefully we are making a difference. It’s been really interesting to get to know some of these kids and let them get to know us and change the opinion. Because at home, some of them don’t have the best opinion of police officers, and we actually get to change that.”

Sawyer described her job as “lots of hugs,” with kids running up and asking the perennial question, “Do you remember me?” Still, her mind often returns to the distrust some kids have shown.

“I remember on a warrant one day, this little kid, I don’t know, about three or four years old,” Sawyer said. “We come in, and he just sticks his tongue out at me, and then spits.”

The Last of the Great Heavyweights

Backstage talking, Lt. Johnson lamented with wry humor that, despite Holyfield’s innumerable achievements, the fight where Mike Tyson bit off a chunk of Holyfield’s ear remains how most people know him best.

Born in 1962, the youngest of nine children to a working class family, Holyfield arrived to high school as one of the highest ranking amateurs in the country, earning him a spot on the 1984 Olympic boxing team, and the bronze medal. From there, Holyfield turned pro and claimed the title by defeating Buster Douglas — and later besting legends George Foreman and Larry Holmes. He was the first fighter to claim the title three times since Muhammad Ali.

When discussing his Olympic years to the Grant audience, Holyfield mentioned the playful conversations he had with famous boxing commentator Howard Cosell. It was Cosell who quit practicing law to cover boxing, a sport where he relished witnessing inner city youths beat the odds and climb life’s ranks by their own powers and talents.

Holyfield told NonDoc that boxing doesn’t have the same import in media today, and he said that affects the number of kids who see it as an escape route.

“You know, boxing, they used to show it all the time,” Holyfield said. “That’s what got me interested as a young kid. Ain’t nobody born heavyweight. But when you start young, you don’t know how big you are going to be. You become a better fighter with those skills. But when you start late, a lot of people don’t take chances when they get older.”