(Editor’s note: This story was authored by Clifton Adcock for Oklahoma Watch and appears here in accordance with the non-profit journalism organization’s republishing terms.)

With less money from the state and bounced-check funds drying up, Oklahoma district attorneys are turning to issuing tickets and putting people on probation through their offices – activities typically left to police, counties and the Department of Corrections.

Their newest revenue-raising effort cracks down on uninsured drivers using a system that scans the license plates of hundreds of thousands of Oklahomans on roadways every year.

In March, the District Attorneys Council, which coordinates state funding for Oklahoma’s 27 district attorneys, recommended a vendor to provide automated license plate scanners. The vendor’s name is being withheld until the contract is finalized.

The scanning devices, which will connect to a database of insured drivers, could start appearing on roadways by the end of the year. Uninsured motorists will get citations in the mail and, if they don’t successfully appeal, pay fines to district attorneys. If they obtain insurance, they can prevent the charges from going on their permanent record. No police or state troopers will be involved in the process.

District attorneys say the purpose of the program is to reduce the large number of uninsured drivers in the state – a problem that pushes up insurance rates and medical costs and contributes to hit-and-run accidents.

But the financial incentive for district attorney’s offices is also strong.

As state funding for their budgets has declined, district attorneys have looked to alternative ways to generate revenue for prosecuting criminals and providing other services.

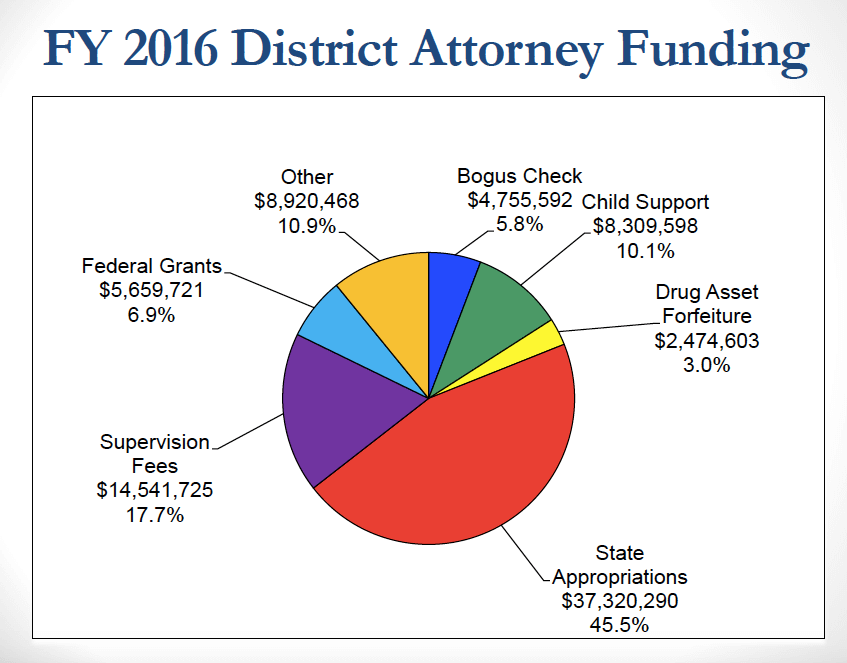

One rapidly growing funding source is district attorney supervision, a form of probation for misdemeanors and some felonies. Offenders pay a $40 monthly fee to DAs’ offices. Since fiscal year 2006 the total amount collected has quintupled to more than $14 million, according to District Attorneys Council figures. The fees accounted for roughly 18 percent of district attorney funding in 2016.

That year, 55,443 people convicted of both felonies and misdemeanors were on DA probation statewide, DA Council figures show. The number of felony offenders on probation exceeded that on Department of Corrections probation.

Advocates of criminal justice reform say the system’s growing reliance on self-funding creates conflicts of interest and could drive up incarceration rates. District attorneys determine whether to prosecute crimes, yet increasingly they are acting as enforcers, prosecutors and offender supervisors.

DA Mike Boring: ‘My victims’ services suck’

The passage of State Questions 780 and 781 in November exacerbated district attorney’s funding concerns.

The initiatives reclassified simple drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor and redirected expected savings from reduced incarceration toward substance abuse treatment. Prosecutors and some lawmakers pushed back, questioning whether voters fully understood the changes.

Several bills were introduced this session to reverse some of the changes. House Bill 1482 sought to allow prosecutors to file felony charges against individuals who are in possession of drugs within 1,000 feet of a school, with some exceptions. That bill did not advance past the House.

Former House Speaker Kris Steele, who led a group advocating for 780 and 781, pointed to prosecutors’ financial incentive to file felony charges, noting that fines and court fees for felony charges are higher than for misdemeanors.

“District attorneys’ offices should not be reliant on these fees and fines for their operations,” said Steele, who now heads an Oklahoma City nonprofit. “It creates an adverse incentive toward corrections reform if you’re relying on these sources of revenue to fund your general operations as a prosecutor or any part of the criminal justice system.”

During debate on HB 1482 in February, Rep. Cory Williams (D-Stillwater) questioned the financial incentives behind aggressive prosecution. Ultimately, he said the blame lies with the Legislature.

“Certainly, we have the tools to (reduce incarceration rates) and have district attorneys charge things as a misdemeanor. Do they? No, they don’t,” Williams said. “Why? Because this body refuses to fund criminal justice in a manner it should be funded.”

That last point will get little argument from Oklahoma prosecutors.

“There isn’t a DA around who won’t tell you, ‘If the state would just fund us, that’s the way it needs to be,’” said District Attorney Mike Boring, whose office represents Beaver, Cimarron, Harper and Texas counties. “My victims’ services suck. I just don’t have the staff. All the staff I have right now are just filling critical needs and prosecution and handling all the stuff we’re mandated to do.”

According to the District Attorneys Council, about 45 percent of funding for DAs’ offices comes from the Legislature – a share that has been declining over the years. The state appropriated $34.5 million to the District Attorneys Council for the current fiscal year, which ends in June. That funding level is no greater than it was 10 years ago, while caseloads continue to grow.

Faced with less money and more work, prosecutors have sought new ways to fund their offices. And the Legislature has been willing to assist.

In 2016, HB 3146 required drunk driving cases to be prosecuted in district court rather than municipal courts. The law redirected a quarter of the total court fees collected from a successful prosecution to the district attorney’s office. Meanwhile, a separate bill doubled the amount of the fees collected in DUI cases.

Another law passed last year allows prosecutors to not charge people with possession of drugs or drug paraphernalia if they agree to DA probation for up to two years. The law also requires them to pay the DA’s office the amount that would have otherwise been paid to the court if criminal charges had been filed.

A lack of state funding could undermine efforts to lower the incarceration rate, some district attorneys say.

“While the Legislature is looking at sentencing reforms and alternatives to prison, at the same time they’re forcing us to cut those alternatives,” said District Attorney Richard Smothermon, who represents Lincoln and Pottawatomie counties.

“If you’re going to plea a guy and send him to prison, you might have to make three appearances on that particular case in court,” Smothermon said. “Whereas drug court doubles the court appearances on the front end, and then it’s a weekly meeting that lasts about three and a half hours. It’s easier to put them in prison than in drug court.”

Ticketed by the DA

Authorized by legislation in 2016, the Uninsured Vehicle Enforcement Diversion Program would allow an uninsured driver to enter a deferred prosecution agreement with the district attorney. The driver would pay the DA’s office an amount equal to the fees that would have been paid to the court had a criminal case been filed. The charge of driving without insurance stays off the driver’s record.

Similar proposals and legislation in other states have been rejected. Among the issues are privacy concerns as they relate to whether data collected on vehicle owners will be kept or shared.

Cleveland and Rogers counties, Oklahoma City, the Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs Control and the Oklahoma Department of Public Safety have discussed or implemented license plate scanners. However, none is using them to catch uninsured drivers.

“What this program does is give someone the ability to: A. Go get the insurance they’re required to have, and B. We put them on the deferred program where there’s not a citation filed against them, so nothing goes on their record,” Boring said.

According to a 2014 report from the Insurance Information Institute, one in four Oklahoma drivers is uninsured. Boring said efforts to bring the uninsured rate down in the past have not been effective.

For the program to work, the state’s motor vehicle insurance database will require upgrades, said DA Council executive coordinator Trent Baggett.

Two bills in the Legislature are aimed at transferring the state’s motor vehicle insurance database from the Department of Public Safety to the Oklahoma Insurance Department. Senate Bill 115 was approved and sent to the governor.

Under the current law, at least 95 percent of motor vehicle insurers in the state, by market share, must be able to report to the database instantaneously before the program can begin. Currently, insurers must report to the DPS-run database, and they may offer real-time verification or upload lists of policyholders.

Transferring control and operation of the database from DPS to the Insurance Department will allow for rules to be created mandating reporting to the database, Boring said, while also allowing for an upgrade to the system’s usability.

“The issue there has been severe lack of funding and the inability of the Department of Public Safety to meet its primary responsibilities and not having the extra money to devote to hardware and software and get that program working,” Boring said.

When the system goes live, there will probably be traffic tests in certain areas of the state, beginning with vehicle-mounted cameras, Boring said. In higher-traffic areas, cameras may be pole-mounted, and movable trailer-mounted cameras may eventually be used, he said.

“The idea is to (eventually) get broad coverage,” he said. “We want to do this on a gradual basis.”

Boring said it’s likely the cameras will not come at a cost to DAs’ offices, meaning that the vendor will likely get a cut of the fees paid under the program.

For those caught by the cameras, the cost will be around $200, Boring said. That is less than if criminal charges were filed and the person would not lose their driver’s license.

Boring said he was not sure how much money the program would generate for district attorneys. It depends on the vendor contract and the effects of a public awareness campaign.

“If we’re half as successful as we hope we can be, after a couple of years that revenue is going to drop,” Boring said.

The goal of the program is increase the number of insured drivers, not bring in money, he said.

“This is a less harsh way of doing that,” Boring said. “If revenue were the driving factor, I’d be saying let’s put one on every street corner.”