A small chink has emerged in the united front coming from Oklahoma’s tribes and the state Attorney General’s Office.

Two of the so-called Five Tribes of Oklahoma have said they are opposed to a purported agreement that would divide how criminal cases will be handled in Indian Country as tribal members started protesting a jurisdiction plan announced by the Attorney General Mike Hunter.

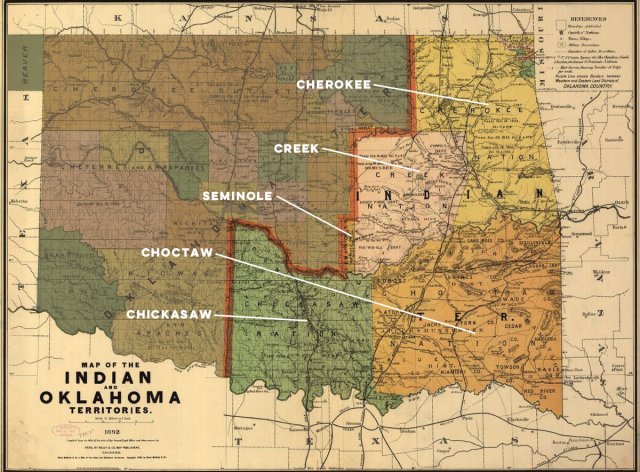

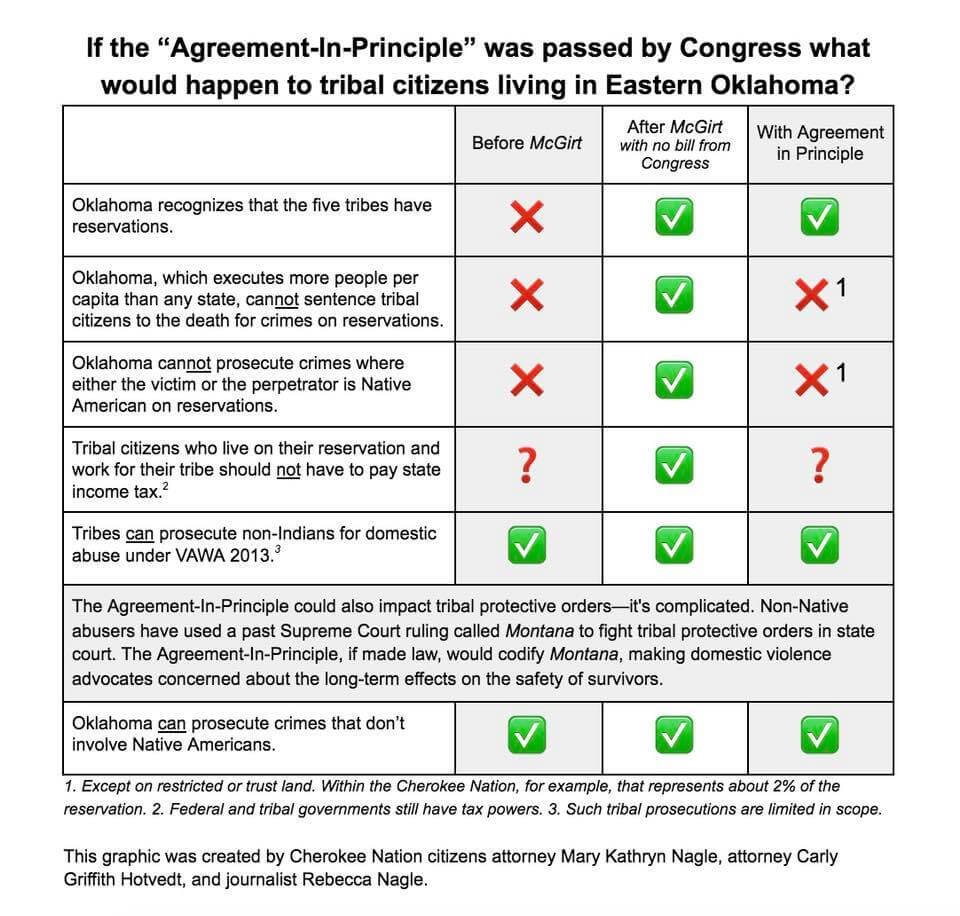

The agreement in principle was announced a week after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in McGirt v. Oklahoma and affirmed the sovereignty of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation over its reservation, which the court ruled Congress had never dissolved. In announcing an agreement, leaders of the Five Tribes and Hunter appeared to deliver a uniform message.

This story was reported by Gaylord News, a Washington reporting project of the Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Oklahoma.

However, the state and tribes’ solidarity developed cracks when the chiefs of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and Seminole Nation changed their tune on the agreement days later.

For former Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation Ross Swimmer, the discord demonstrates the complexity of the McGirt decision.

“There is nothing like this — that is, in Indian Country — of which I am aware,” he said. “I’ve not heard or seen anything of this consequence. So the complexity is, what do we do now?”

Some Cherokee citizens say they weren’t consulted before the agreement was announced.

“What is so offensive about what the chief was doing is that his attempts to work with the attorney general and get something out there to influence Congress was just him. It wasn’t us,” said David Cornsilk, who helped organize a protest last week at a Cherokee Nation tribal hearing.

“He was elected by us, but he didn’t come to us and say, ‘What is it that you want?’” Cornsilk said.

The appeals of McGirt

Hunter’s proposed agreement solidified the tribes’ jurisdiction over crimes involving native citizens within the treaty territory. However, it also maintained the state’s role with a clause ensuring its concurrent jurisdiction in previously disputed territory, leaving only crimes committed by native citizens on restricted or trust land beyond the state’s reach. Federal legislation is needed to codify the changes.

The case concerned an appeal from Jimcy McGirt, a citizen of the Seminole Nation, who claimed that since his crimes occurred within the historical boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek) reservation, Oklahoma courts had no jurisdiction to convict him. Instead, he should have been tried in federal court, the Muscogee (Creek) and his lawyers argued.

For the Five Tribes, the high court’s decision also handed back jurisdiction over the misdemeanor and other more minor crimes that occur on their reservations, a prospect that many tribal citizens say is an invaluable element of a sovereign nation’s rights.

Many tribal citizens said the proposed concurrent jurisdiction plan failed to live up to McGirt’s potential.

Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s Principal Chief David Hill said in a statement that intergovernmental compacts would be preferable to congressional legislation in solving confusion surrounding the case.

“There exists the real possibility that outside interests opposed to any gains by Indian tribes will unilaterally pursue federal legislation that could reverse what McGirt did, or even possibly do far more damage to tribal sovereignty,” he wrote.

Hill’s denouncement of the proposed agreement was joined by Seminole Nation Chief Greg Chilcoat, who said his tribe had not approved the agreement nor been involved in any negotiations with Hunter addressing their sovereign rights.

However, leaders from the Cherokee, Chickasaw and Choctaw nations remained firm in their support of the compact. A joint statement issued by the three tribes stressed that, while they agreed that more consideration should be given to the views of tribal citizens in further discussions, they had no intention of backing out of the agreement.

“None of the leaders of the Five Tribes support eroding our sovereignty or turning back the recognition of our reservation achieved through McGirt,” the statement read.

U.S. Rep. MarkWayne Mullin (R-OK2) also urged the tribes to take their time in negotiating an agreement with the state.

“Instead of moving too quickly and causing unintended consequences, which negatively impact generations of Oklahomans to come, we must be conscious and deliberate in our efforts to ensure we get this right,” the five chiefs and Mullin, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, said in a joint-statement.

Swimmer, who helped cement the status of the Cherokee government as a sovereign nation when the U.S. secretary of the interior approved the Cherokee Constitution in 1975, said he never imagined a victory as large as the McGirt decision.

“It feels like, you know, we’re making progress from what happened to us and statehood where it appeared that everything was taken away from the tribe,” Swimmer said.

In the aftermath of the McGirt decision, Swimmer said a collaboration between the tribes would be essential.

“I’m afraid that if the tribes don’t come together quickly and develop their position (…) they’re going to be at the mercy of the state governor and Legislature and the congressional delegation,” he said.

According to statements from the leaders of the Five Tribes and Hunter, all parties remain open to continuing negotiations on McGirt, despite their differing stances.

But Cornsilk said he is concerned his tribe will give up much of the jurisdiction it earned for fears of overwhelming its resources and court system.

“We have a chief who has turned to mother Oklahoma and said, ‘Your children, the Cherokees, are not ready. We’re not mature enough, we’re not capable, so we need your help,’” he said. “I don’t believe there is anything wrong with asking for help, but you’ve got to know that you need it, and they don’t know that right now.”