The U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark decision in favor of tribal sovereignty Thursday morning, which could see far-reaching ramifications beyond criminal law. The federal government, not the state of Oklahoma, has jurisdiction over major crimes that occur on tribal lands in the state, the court ruled. The statute interpreted by the court defines Indian Country and has been used for civil purposes in many other contexts, including taxation, environmental laws and other regulations.

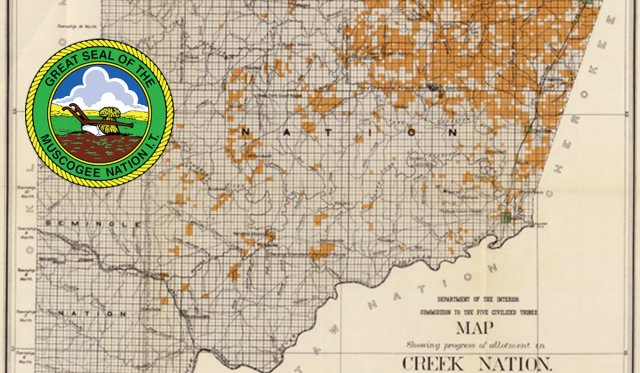

The majority opinion on McGirt v Oklahoma, which was written by Justice Neil Gorsuch, asserts that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s tribal reservation established by Congress in the 19th century remains in effect for the purposes of federal criminal law. The opinion would appear to apply to 19.7 million acres in eastern Oklahoma across the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole nations as well. Though the state of Oklahoma has prosecuted cases that take place on tribal land, Gorsuch wrote, it is the federal government who has jurisdiction to do so under the Major Crimes Act.

“Today we are asked whether the land these treaties promised remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law. Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word,” the opinion states.

Shortly after the SCOTUS ruling was announced, the state of Oklahoma joined the Muscogee (Creek), Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole nations in releasing a statement that they “have made substantial progress toward an agreement to present to Congress and the U.S. Department of Justice “resolving any significant jurisdictional issues” raised by the McGirt decision.

“The nations and the state are committed to ensuring that Jimcy McGirt, Patrick Murphy, and all other offenders face justice for the crimes for which they are accused. We have a shared commitment to maintaining public safety and long-term economic prosperity for the Nations and Oklahoma,” the statement read. “The nations and the state are committed to implementing a framework of shared jurisdiction that will preserve sovereign interests and rights to self-government while affirming jurisdictional understandings, procedures, laws, and regulations that support public safety, our economy, and private property rights. We will continue our work, confident that we can accomplish more together than any of us could alone.”

Court says Creek Nation remains a reservation

The case, which was heard by the Supreme Court on May 11, raised three questions: Whether the Muscogee (Creek) Nation ever had a reservation; whether that reservation (if it existed) was disestablished by statehood; and whether ruling in favor of McGirt would effectively invalidate thousands of convictions for crimes on tribal land.

In Gorsuch’s 42-page majority opinion, the court held that the land was and continues to be a reservation, and that while some cases will need to be re-tried, it will not place an undue burden on the courts. Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor joined Gorsuch’s opinion. Chief Justice John Roberts dissented and was joined by justices Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh and Clarence Thomas, in part. Thomas filed a separate dissent.

This is not the first case the Supreme Court has heard on the issue of tribal sovereignty in Oklahoma. Last session, a similar case, Sharp v. Murphy appeared before the court to ask whether the territorial boundaries of the Creek Nation established in 1833 still stood. In a rare move, the justices failed to come to a decision on the case, likely reaching a tie due to the recusal of Gorsuch, who had heard the case while serving on a lower court.

In withholding a ruling on Sharp v. Murphy, the court also decided it would take up the McGirt case, which raised many of the same issues and could be voted on by all nine justices. The decision in Sharp was released Thursday along with the McGirt opinions, saying that for the same reasons stated in McGirt, the decision in the 10th Circuit Court in favor of tribal jurisdiction was upheld.

In his McGirt opinion, Gorsuch asserted that the land assigned to Native American tribes forcibly moved to Oklahoma “remains ‘Indian Country’” for the purposes of the Major Crimes Act, a law which denies state governments the jurisdiction to prosecute certain crimes that occur on tribal reservations. Gorsuch wrote that Congress had never clearly stated its intent to disestablish what was historically referred to as a reservation. The reservation still exists in Eastern Oklahoma, according to the opinion, and Jimcy McGirt’s crimes took place on the reservation, voiding the state of Oklahoma’s prosecution and conviction of McGirt on rape charges.

How a rape trial became a sovereignty case

McGirt v. Oklahoma began as an appeal for McGirt, a citizen of the Seminole Nation who was convicted of raping a minor on Creek Nation land. McGirt’s lawyers argued that his conviction was invalid because he was convicted by the state of Oklahoma, who does not have jurisdiction to rule on cases that occur on tribal lands or involve citizens of tribal nations. The core question of his appeal was whether the land in question — and crimes committed on it — fall within the jurisdiction of the state of Oklahoma or tribal governments.

During the May 11 telehearing, McGirt’s attorney, Ian Gershengorn, argued that the Major Crimes Act of 1885 invalidated McGirt’s original prosecution and conviction in Wagoner County District Court. The MCA gives only the federal government jurisdiction to prosecute major crimes, including rape, that occur on reservations.

While the state attempted to posit that Oklahoma’s reservations were unofficially dissolved at statehood, Gershengorn countered that historically Congress has used clear language of its intent to disestablish reservations.

“Congress did not transfer criminal jurisdiction to Oklahoma. At statehood, the Major Crimes Act established exclusive federal jurisdiction over enumerated crimes in ‘any state of the United States,’” Gershengorn said. “When Congress overrides the Major Crimes Act and transfers jurisdiction to a state, it does so expressly, and it did not do so here.”

‘Never a reservation’: The losing state arguments

The state of Oklahoma, represented by Solicitor General Mithun Mansinghani, presented an argument heard for the first time by the court.

“Oklahoma has jurisdiction over the eastern half of the state because it was never a reservation and certainly is not a reservation today,” Mansinghani said in oral arguments.

According to Mansinghani, the land referred to as the Creek reservation was actually a “dependent Indian community,” because the land was held by “fee-simple” rather than by an Indian right of occupancy. While reservations must consist of land reserved from sale, the fee-simple land interest definition allows land to be sold.

The Supreme Court found these arguments to be unconvincing, holding that Congress did establish a reservation for the Creek tribe in 1833 and citing a later treaty in 1856 that promised “the Creeks would have the ‘unrestricted right of self-government,’ with ‘full jurisdiction’ over enrolled tribe members and their property.”

“Congress established a reservation, not a dependent Indian community, for the Creek Nation,” the opinion holds.

The Court also disagreed with the second portion of the state’s argument, which held that regardless of the initial classification of the land, any special distinction given to the land was removed by Congress when it lifted federal restrictions in preparation for statehood, ending tribal jurisdiction.

“Congress was trying to undo the tribe’s exclusive ownership of the land,” Mansinghani said of Congress’s abolishment of tribal courts and prohibition of distinct treatment of Indians. By taking these actions, he argued, Congress intentionally stripped the land of any “Indian interest.”

However, the majority opinion states, once a reservation has been established, only a clear expression of disestablishment by Congress can reverse that, and no such expression exists in this case. Though Congress did attempt to pressure tribes to abandon aspects of their lifestyle during the “allotment era,” they never removed the lands from tribal interest.

Retrials expected

When Oklahoma became a state, all cases involving Native Americans were transferred from federal to state jurisdiction. This pattern of prosecution has been the norm for more than a century, meaning the McGirt decision could call into question more than 3,000 cases involving citizens of tribes, according to Mansinghani.

These arguments were troubling to the court, which held that “historical practice and demographics” are not sufficient to prove disestablishment of a reservation.

“In the end, Oklahoma resorts to the state’s long historical practice of prosecuting Indians in state court for serious crimes on the contested lands, various statements made during the allotment era, and the speedy and persistent movement of white settlers into the area,” the opinion reads. “But these supply little help with the law’s meaning and much potential for mischief.”

During the May 11 hearing, Gorsuch asked Gershengorn about the “terrible practical consequences” of a ruling in favor of his party, including concerns over potentially thousands of state prosecutions of Native American crimes on reservation land, which would now be eligible for retrial.

Gershengorn said he believed a majority of those eligible for retrial would choose not to exercise the option, as being prosecuted by federal courts would likely result in more severe sentences.

“I think that federal penalties will often be higher, and I think that a number of defendants will have already served large chunks of their sentence,” Gershengorn said. “There is no evidence that the state has put forward that there will be enlarged numbers (…) the type of tsunami that has been predicted just wouldn’t materialize.”

Though the court acknowledged the concern that a decision in favor of McGirt will have consequences in many cases that have already been decided by the state, they did not see this as reason enough to rule in the state’s favor. Though the federal government may have to retry cases Oklahoma previously prosecuted that took place on tribal lands, the court expressed faith that would not present an unreasonable challenge.

The decision brings more uncertainty for Oklahoma state government, as the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Seminole and Choctaw could pursue further legal action to expand their own sovereignty. State leaders may also pursue legislation in Congress to ensure their jurisdiction remains to prosecute non-tribal citizens who commit crimes on reservations within state boundaries.

“This Court is aware of the potential for cost and conflict around jurisdictional boundaries,” Gorsuch wrote. “But Oklahoma and its tribes have proven time and again that they can work successfully together as partners, and Congress remains free to supplement its statutory directions about the lands in question at any time.”

State, tribal leaders respond

Oklahoma’s two U.S. senators released statements Thursday morning about the McGirt decision. Each signaled toward future action.

“Our greatest priority should be to provide for the safety of communities by ensuring those serving time for crimes continue to do so, and individuals that commit crimes are prosecuted to the fullest extent under the law,” U.S. Sen. James Lankford said. “I look forward to working with the tribes, the state, and other members of the Oklahoma congressional delegation to finding a solution acceptable to all parties.”

U.S. Sen. Jim Inhofe concurred.

“As we move forward, I have no doubt we can work together with state officials, tribal organizations, and the delegation to find a workable solution for everyone that ensures criminals are prosecuted and brought to justice in the most appropriate manner,” Inhofe said. “We have a duty to all American citizens to uphold the Constitution and stand up for victim’s rights. Our number one priority will always be the safety of each and every Oklahoman.”

All five of Oklahoma’s U.S. House members released a joint statement later Thursday.

“We are reviewing the decision carefully and stand ready to work with both tribal and state officials to ensure stability and consistency in applying law that brings all criminals to justice,” the statement read. “Indeed, no criminal is ever exempt or immune from facing justice, and we remain committed to working together to both affirm tribal sovereignty and ensure safety and justice for all Oklahomans.”

Thursday afternoon, Chickasaw Nation Gov. Bill Anoatubby released a statement on Twitter.

“We applaud the Supreme Court’s ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma, which holds that the Creek Nation’s treaty territory boundaries remain intact. We appreciate the Supreme Court’s affirming the United States’ treaty promises and we celebrate the court’s recognizing that Oklahoma and the tribes consistently ‘have proven they can work successfully together as partners,'” Anoatubby said. “Tribal and state law enforcement agencies have worked cooperatively for years to serve and protect our communities. We are accustomed to the unique context of overlapping tribal and state jurisdictions and will continue to work together to ensure public safety and effective law enforcement throughout Oklahoma. Regardless of any court ruling, far more unites us than ever separates us, and the Chickasaw Nation looks forward to continuing its cooperating and collaborative partnerships with state and local law enforcement to ensure public safety and well-being throughout Oklahoma.”

Around 5:30 p.m., Gov. Kevin Stitt was asked about the McGirt decision during a press conference and said his administration is “still digesting that.”

“Obviously with the criminal cases, it’s going to have an impact on Oklahomans, but it (…) could have other implications for the state of Oklahoma,” Stitt said. “We’re still talking to the experts to see exactly what that means for the state of Oklahoma.”

Stitt said he had spoken with Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter earlier in the week and with Lankford earlier Thursday.

“Does it stop the prosecution of (some) crimes? Does it move into taxations? All those questions are things that nobody really knows at this point,” Stitt said. “This is a federal issue. It’s something that Congress needs to address to put some parameters and see exactly how we are supposed to deal with this.”

Oil and gas group ‘disappointed’

Brook Simmons, president of the Petroleum Alliance of Oklahoma, released a statement Thursday afternoon that referenced concern about the potential for new severance taxes imposed by tribal nations in the wake the McGirt decision.

“The Petroleum Alliance of Oklahoma is disappointed in today’s majority opinion in McGirt v. Oklahoma, but we are moving forward to work with the state of Oklahoma, the tribes and Oklahoma’s congressional delegation to ensure that our members continue to have a stable, predictable regulatory and tax environment consistent with their interests,” Simmons said. “It is critical for continued investment in Oklahoma that the state maintain primacy with regard to the regulation of oil and gas operations, and that issues of title with regard to real property remain unaffected.”

(Update: This story was updated to include the joint statement from congressional members at 12:20 p.m. Thursday, July 9. It was updated again around 3:50 p.m. to include comment from the Petroleum Alliance of Oklahoma and Anoatubby. It was updated a final time at 5:45 p.m. to include comment from Stitt.)