In the most public and in-depth conversations between tribal and non-tribal leaders since a landmark 2020 U.S. Supreme Court decision functionally affirmed nearly half the state as a series of Indian Country reservations, elected officials and attorneys from four large tribal nations spoke Tuesday to members of the Oklahoma House of Representatives about the history of state-tribal compacts on a variety of topics, including tobacco taxation and motor vehicle licensure agreements that were extended one year this summer and that will be the focus of further negotiation in 2024.

With Gov. Kevin Stitt having the most contentious relationship with tribal nations of any Oklahoma governor this century, exactly how compact renewal negotiations will unfold over the next year remains unclear, but House Speaker Charles McCall said after the first session of his two-day interim study that it’s clear tribal leaders “want legislative leaders in the conversation.”

“I think what we also heard from them today is that they don’t believe the Legislature receives any communication from the governor on the talks and the discussions. They define what they see as a negotiation versus a demand. And that’s a valid point, because the governor does not communicate with us in terms of what conversations he has had — what communication he’s having, either written, verbal or other means,” said McCall (R-Atoka). “So going forward, everybody needs to know what everybody is saying, but it’s not so much ‘the what,’ it’s ‘the how.’ And I think for us to really get to the finish line on a compact extension, a renewal, a new compact — if something comes up in the future that we haven’t taken up before that we need to address, it’s going to happen by the leaders sitting down and talking.

“The Legislature is going to be involved going forward.”

Participants in McCall’s study heard that — in the 30-year history of Oklahoma’s more than 900 state-tribal compacts — different agreements have been established in different ways, some involving only legislative action, some involving only gubernatorial negotiation, and others involving both.

“If we had a document that says this is how we compact, this is the procedure we follow, I think it would be a great help to both sides and take away some of the uncertainty,” said Mike Burrage, the longtime general counsel of the Choctaw Nation. “Everybody would know what the path is, and if there is an issue how we’d resolve (it).”

Put lightly, there have been plenty of “issues” as a slew of state-tribal compacts — on casino gambling, tobacco taxation, motor vehicle registration and hunting and fishing licenses — have approached their expiration dates during Stitt’s time as governor.

Sometimes owing to concerns about the McGirt v. Oklahoma‘s decision potential impact on civil regulatory jurisdiction and sometimes owing to his belief that the state should have previously negotiated a “better” deal, Stitt has insisted he will not be “a rubber stamp” on compacts coming up for renewal. His strategy ended a pair of hunting and fishing compacts with the Cherokee and Choctaw nations, which functionally decreased state revenue owing to how federal payments are calculated based on overall license numbers. Tribal leaders sued Stitt and won a ruling that determined the state’s Model Tribal Gaming Compact had renewed automatically owing to action taken by the Oklahoma Horse Racing Commission.

Most recently, the Legislature overrode a pair of Stitt vetoes this summer to extend existing tobacco taxation and motor vehicle licensure compacts by one year, a tumultuous political chapter set to repeat itself in 2024.

“Having good state-tribal relations requires something of all of us,” Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. said during Tuesday’s study. “And it requires understanding that the exercise of tribal sovereignty, whether expressed through a compact or any other way we exercise sovereignty, doesn’t come at the expense of the state of Oklahoma.”

The McGirt decision has fundamentally changed criminal jurisdiction rules in more than 40 percent of the state, however, and initial 2020 efforts to establish new and broad public safety compacts quickly fell apart. Now, tribal citizens accused of a crime within the Muscogee (Creek), Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole, Quapaw, Ottawa and Peoria nations may only be prosecuted by a tribe or the federal government, not the state.

Stitt has railed against the legal duality, pushing legal challenges that led to a subsequent landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta that upended decades of widely perceived Indian law precedent by saying the state has concurrent jurisdiction to prosecute non-tribal citizens who commit crimes against tribal citizens within Indian Country reservations.

During Tuesday afternoon’s panel involving attorneys from the Chickasaw, Choctaw and Cherokee nations, House Appropriations and Budget Committee Chairman Kevin Wallace (R-Wellston) read questions from other legislators. Wallace asked the panel members if they could see an avenue where the state of Oklahoma could have “dual jurisdiction” to prosecute crimes committed by tribal citizens on the reservations.

Burrage provided the only response, which could signal an opportunity to revive the public safety compact conversation but could also irritate some tribal citizens who might view a return to concurrent prosecutorial jurisdiction a relinquishment of tribal sovereignty.

“There is a path forward for concurrent jurisdiction, and that situation existed for a long time prior to McGirt,” Burrage said. “As the tribes have recognized, that path — there’s a clear path forward on that when it comes to compacting.”

Civil law questions ‘don’t have a judicial resolution (…) yet’

The question of criminal jurisdiction in eastern Oklahoma highlights a key and disputed phrase in the McGirt majority opinion: “For [Major Crimes Act] purposes, land reserved for the Creek Nation since the 19th century remains ‘Indian country.'”

“McGirt was a U.S. Supreme Court decision that dealt with the Major Crimes Act and what was Indian territory within the Major Crimes Act. It wasn’t a civil lawsuit,” Burrage said Tuesday. “Look at McGirt for what it is, but don’t take it for what it’s not. That’s what a lot of people have done and that’s what has caused a lot of emotional outbreaks and so forth against the tribes, I think, and it’s a position the tribes never took.”

Despite Burrage’s claim, attorneys for the Chickasaw, Cherokee and Choctaw nations — the three tribes represented during Tuesday afternoon’s second panel discussion — have taken that position in court, specifically citing the McGirt decision’s affirmation of the Muscogee (Creek) Reservation in an amicus brief supporting Muscogee citizen Alicia Stroble’s appellate case arguing that she is exempt from state income tax authority because she lives and works within her tribe’s reservation.

“McGirt plainly held that the Creek Reservation survived allotment and remains intact today,” the Chickasaw, Cherokee and Choctaw attorneys wrote. “Therefore, the provisions of Oklahoma Administrative Code (…) now apply in all lands within the Reservation boundaries described in the Muscogee (Creek) Treaty of 1866.”

If Stroble prevails in her case, which is set for oral arguments before the Oklahoma Supreme Court on Jan. 17, Choctaw Nation Chief Gary Batton said this summer that a new compact on income taxation might make sense.

“As a sovereign nation, our tribal members, I do not believe that they should be taxed,” Batton said in July. “However, we are all Oklahomans, and we do need to pay our fair share. I think there’s a compact on taxation that should come into place at some point in time in the future.”

Stroble would appear to have a strong case for exemption from state income taxation owing to the plain language of state code and the 1993 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Oklahoma Tax Commission v. the Sac and Fox Nation, which found:

Absent explicit congressional direction to the contrary, we presume against a state’s having the jurisdiction to tax within Indian country, whether the particular territory consists of a formal or informal reservation, allotted lands, or dependent Indian communities.

While Wallace said Tuesday he believes the Oklahoma Supreme Court will rule in favor of the state Tax Commission, he is prepared for policy discussions if tribal citizens who live within reservation boundaries are affirmed to be exempt from state income tax.

“If it is, I think we will end up redoing the tax base for the state of Oklahoma, because we will not have two separate tax codes,” Wallace said. “It will be fair and equitable for all Oklahomans, no matter your race and ethnicity.”

Committee members were told Tuesday by attorneys who testified to remember that the designation “Indian” is more a political classification than a racial classification, with sovereign tribal nations having the ability to determine their membership. They were also reminded that the McGirt decision’s affirmation of reservations in Oklahoma has not changed the rights, protections and sovereignty afforded to Indians.

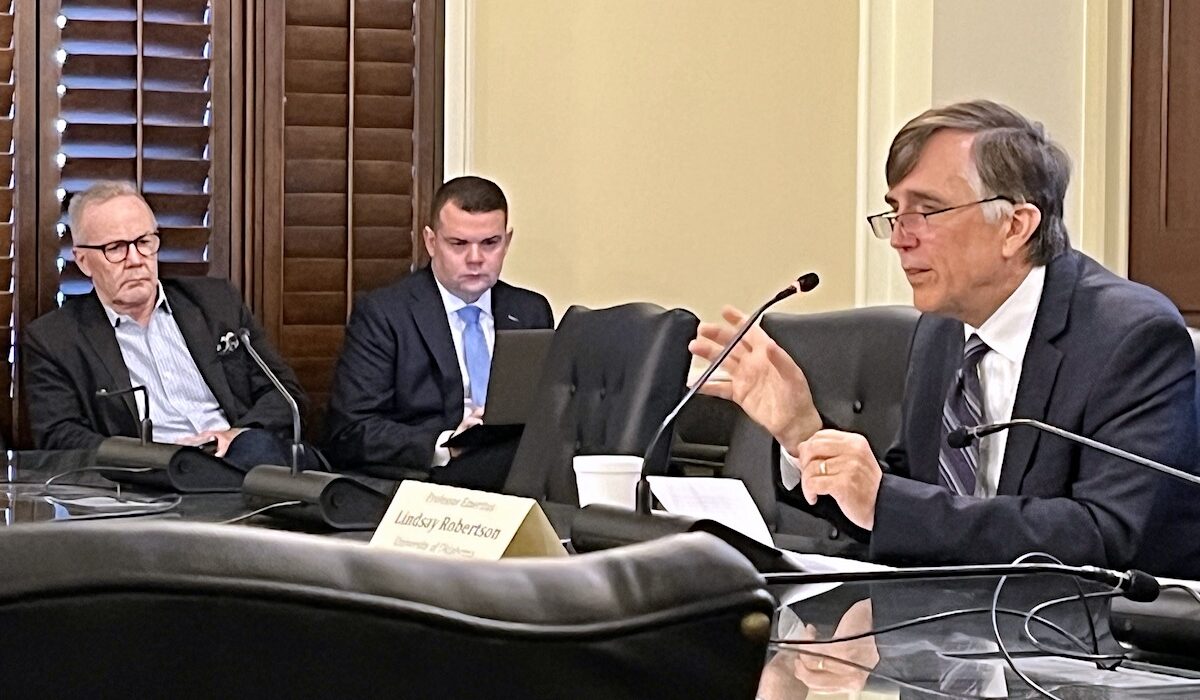

However, it has expanded the land that qualifies as “Indian Country,” which Indigenous law professor Lindsay Robertson called “a term of art” while testifying Wednesday about the undetermined extent to which eastern Oklahoma is now Indian Country for civil regulatory jurisdiction, which includes matters like taxation.

“So now that it’s Indian Country, does the state of Oklahoma still have civil law jurisdiction over it? And the answer is, we don’t definitively know,” said Robertson, who worked on tribal law and compacting issues in the administrations of Republican Gov. Frank Keating and Democratic Gov. Brad Henry.

Robertson noted that the idea eastern Oklahoma could be a reservation for criminal law purposes but not a reservation for civil regulatory purposes would be peculiar.

“We don’t have a judicial resolution of that question yet,” Robertson said. “I would say as a fairly informed spectator, I would think if the court were to find Muscogee Nation were Indian Country for one purpose but not another, it would be the first time in history that that line had been drawn.”

Asked if he thought having the reservations exist for criminal purposes but not civil purposes would be a functional way to govern society, Wallace replied, “No, I do not.”

Anoatubby: ‘I hope we can come to terms’

When legislators return for regular session in February, Tuesday’s conversations — and interviews with elected officials afterward — hinted that tribal-state compact negotiations could be different in 2024.

For instance, Chickasaw Nation Gov. Bill Anoatubby said the Stitt administration’s July decision to release emails to NonDoc showing back-and-forth conversations and red-lined documents on a potential tobacco tax compact extension chilled the negotiation process.

“These days I don’t put anything in an email,” Anoatubby told lawmakers Tuesday, one day before his 78th birthday. “There was nothing real earth-shattering there. I just feel like negotiations need to be a little more confidential.”

McCall agreed, praising the abilities of retired Oklahoma Supreme Court Justice Steven Taylor but questioning the Stitt administration’s insistence that Taylor join a meeting at the Chickasaw Nation’s Oklahoma City headquarters.

“When you have current leaders of nations or sovereigns in this case, those people have to get together and agree to terms of engagement. It can’t be one-sided,” McCall said. “The failings of those meetings is not due to any individual specifically. It’s a failure because the co-equals did not have an agreed-upon process, and when somebody tries to interject something foreign into a process that is not agreed to, it creates distrust and it makes it harder to move forward. You start from a position of having to regain trust before you can take that step forward.”

Asked how further conversations on the expiring tobacco and motor vehicle licensure compacts might unfold, Anoatubby said after Tuesday’s hearing that he is unsure but that tribal nations “need to be on the same page.”

“We can’t approach it the same as we did before. It was just us negotiating. We have other tribes in the state now engaged, so we’re going to have to get together before we can actually deal with it,” Anoatubby said. “I hope we can come to terms. (…) It’s going to be dependent upon the tribes getting together, and we’ll work on that. I’m hopeful, that’s all I can say.”

The other tribal leaders who testified Tuesday also expressed hope for a new chapter of tribal-state negotiations this decade, particularly as it relates to finding a tobacco compact agreement.

“The environment we’re in, plainly, is one in which the tribes and the Legislature itself favors it having a more prominent role in compacting, and I think they’re doing their homework — literally — in anticipation of that,” Hoskin said after Tuesday’s hearing. “I think there is an opportunity. I appreciate the Stitt administration put forth something. I think my colleagues on the panel summed it up nicely, which [felt like], ‘This is the only path forward, take it or leave it,’ was perhaps the implication. But I’m willing to be optimistic that it’s the first of what could be other discussions.”

Wes Nofire, a former Cherokee National Tribal Council member who has clashed with Hoskin, attended Tuesday’s panels and said afterward it was important to remember that only four of the state’s 38 federally recognized tribal nations received seats at McCall’s table.

“Working out of the governor’s office, we’ve always maintained an open door policy to communicate with anyone, not just the tribes that were there today, but all of our federally recognized tribes in the state,” said Nofire, whom Stitt designated as his Native American liaison in September. “And so I want to make sure that beyond just the tribes that were their representing their constituents, we have many other tribal governments in the state who didn’t have the opportunity to reflect their voices.”

Nofire’s comment underscored Stitt’s history of aligning his interests more often with smaller tribal nations that have historically faced obstacles to casino industry development from the larger tribes represented Tuesday.

But Hoskin said Stitt’s remarks for the past five years have made it difficult for tribal citizens and their elected officials to view him as a trustworthy partner in compact negotiations.

“I think he means what he says when he makes his public statements about tribes. I take all of it to mean he doesn’t really see a world in which tribal governments ought to be exercising sovereignty, and to the extent he has to deal with it, it’s a business deal and the state should get more by us getting less,” Hoskin said. “I think that’s going to continue to inform his understanding of state-tribal relations. I don’t really see people around him that are really in a position to advise him otherwise, but we do have a Legislature who are, frankly, the adults in the room when it comes to a genuine understanding and a desire to go forward.

“I think we may have to work around the governor, but he’s the governor, and to the extent that he’s making offers, we ought to be responsive to that.”

Still, Hoskin said he is holding out hope for renewed and improved negotiations about the tobacco and motor vehicle licensure compacts in 2024.

“I think it is going to take the tribes coming together with one voice, because the tobacco compact is of the nature where you want some market certainty all over the state, at least where the compacts apply,” Hoskin said. “There’s still hope. We have some time, and perhaps today’s meeting will remind us all that we need to achieve some results on those compacts, and I don’t want to rule out that we could do it with the governor, because we could.”

Nonetheless, those who spoke during McCall’s two-day study emphasized the value of having a public meeting where critical history and legal perspectives could be shared.

“Today is a remarkable day. Let’s aim to make it less remarkable by doing this more. No one is breathing fire. Everyone wants what is best for the state of Oklahoma,” said Chickasaw Nation special counsel Stephen Greetham, whose remarks focused largely on the tenants of tribal sovereignty and Oklahoma’s legal lack of standing to regulate tribal governments. “When you come to those points where the state can’t control the tribes and the tribes can’t control state (…). When you reach that point, do you dig in and approach each other as adversaries, or do you sit down and try to figure out ways to problem-solve with each other?”

Cherokee Nation Attorney General Chad Harsha said compacts are often “mischaracterized as a commercial type of contract or business agreement” instead of documents crafted to recognize specific rights drawn from treaties and avoid “high-risk issues” that could otherwise draw litigation and acrimony.

“I think compacting is a good way to resolve some of these disputes,” he said.

Muscogee Nation Second Chief Del Beaver summed up Tuesday’s first panel by saying open conversations on tribal-state relations “should be more commonplace.”

“I think we’re at the cusp of something special,” Beaver said. “Just because a compact worked and was agreed upon 10 years ago doesn’t mean it’s going to work and be agreed upon today, because all the tribes are different from 10 years ago. The state of Oklahoma is is a different place than 10 years ago, so our perspective changes. Especially since McGirt, it has changed.”

Beaver and his counterparts with the Chickasaw, Choctaw and Cherokee nations said virtually none of the state’s slate of elected officials were in office when major compact negotiations occurred 10 and 20 years ago, meaning a loss of institutional memory can jeopardize the opportunity for informed negotiation now.

“There have been far too many times that a tribe has been the subject of a conversation, but we have not been part of that conversation. That’s where we get sideways, where there are conversations about us but we are not part of that conversation,” Beaver said. “Moving forward, when decisions are going to be made, we need to be at the table.”