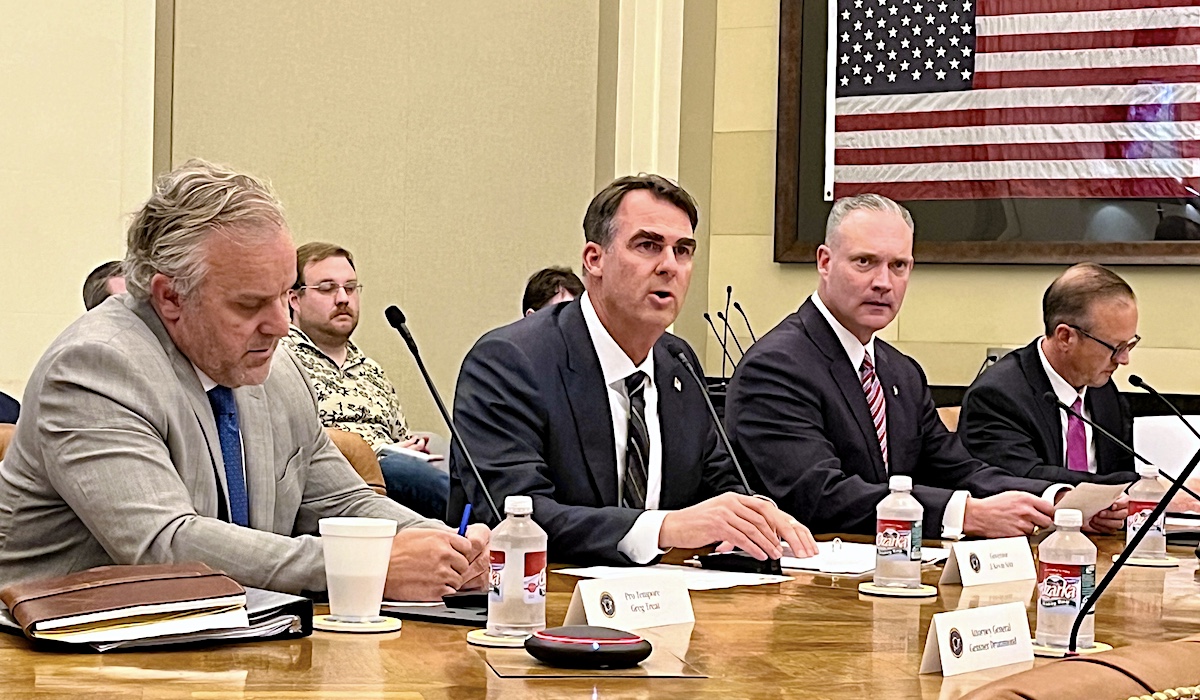

An agreement has been reached to settle a lawsuit alleging unconstitutional delays of mental health competency restoration services for pre-trial defendants in Oklahoma who have faced extraordinary wait times for treatment of severe mental illness. Gov. Kevin Stitt and Attorney General Gentner Drummond, who in recent months had been at odds with each other over the litigation, announced the agreement in separate press releases today.

Paul DeMuro, the lead attorney for plaintiffs in the class-action litigation, said the modified agreement was hammered out during an 11-hour meeting Wednesday with assistance from T. Lane Wilson, a former magistrate judge who DeMuro said offered to moderate the negotiations.

“I am super excited about it,” DeMuro told NonDoc. “I think this is a great consent decree — a great day for the state of Oklahoma. And now we’ve got to fix the problem.”

Ultimately, DeMuro said “everybody recognized the system was broken” for mentally ill defendants awaiting competency restoration services, which typically involve the administration and monitoring of anti-psychotic medications.

“At the end of the day, the momentum behind that recognition compelled the stakeholders to reach a resolution,” DeMuro said. “And somewhere along the line, everybody set aside their political animus and got down to business for the people of Oklahoma, and that’s really encouraging. The governor and the attorney general should be applauded.”

Stitt’s office said attorneys representing the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services worked with plaintiffs’ attorneys to reach an agreement.

“Commissioner Allie Friesen has worked tirelessly to promote the well-being of Oklahomans in state custody while ensuring Oklahoma taxpayers aren’t on the hook for tens of millions of dollars in attorney and consultant fees,” Stitt said in a press release. “I am proud of her leadership. This deal will resolve the issues at hand in this lawsuit without keeping Oklahoma taxpayers in an endless settlement agreement that puts the health of Oklahomans at risk.”

Twenty-four minutes after Stitt’s announcement, Drummond’s office issued a release saying Drummond and plaintiffs’ attorneys reached an agreement.

“This settlement is a significant win for Oklahoma,” Drummond said in his release. “Victims and their families no longer will have to endure unnecessary delays for justice to be served, our criminal justice system will be rid of problems that have plagued it for years and Oklahomans will save tens of millions in taxpayer dollars by avoiding the costs and risks of ongoing litigation.”

DeMuro said neither Stitt nor Drummond was present for Wednesday’s negotiations. He said a PDF version of the lengthy agreement could be released publicly “maybe tomorrow.”

Contingency Review Board, federal judge approval remain

Filed in March 2023, Briggs et al v. State alleges ODMHSAS and the Oklahoma Forensic Center in Vinita have violated due process rights of some pretrial defendants by failing to provide timely court-ordered competency restoration services. Some detainees deemed incompetent to stand trial have been denied treatment and have languished — without a trial — in county jails for more than a year, resulting in delayed justice for crime victims.

The proposed consent decree outlines a strategic plan for justice to be administered in a timely fashion by improving ODMHSAS’ restoration services, according to the AG’s Office. A consent decree is a monitored settlement agreement for litigation that includes benchmarked improvement of state services. A panel of “experts” is prescribed to monitor the plan’s implementation.

The three-member Contingency Review Board, which Stitt chairs as governor, is expected to consider the revised consent decree sometime in January. The Contingency Review Board considers major state lawsuit settlements when the Oklahoma Legislature is not in session. It rejected a proposed settlement last month over the objections of Drummond who argued via email that it was premature for the board to act and that Stitt’s eagerness to reject the proposal was “bewildering.”

DeMuro said changes agreed to Wednesday include modifying the consent decree to make it clear ODMHSAS can provide competency restoration services to people in jail settings, so long as they are legitimate and professionally recognized services that are signed off and approved by the panel of independent experts that will be established to monitor compliance with the decree.

“The main aspect was that the commissioner and the governor wanted assurances that the department would still be able to provide restoration treatment services to people who were in jail, notwithstanding the fact that the consent decree obligated them to cease the sham statewide restoration program they had rolled out as a dishonest mechanism to avoid judicial scrutiny in [early] 2023,” DeMuro said.

The consent decree carries a five-year term, but the parties agreed Wednesday that there can be “an early exit ramp that incentivizes the department if, after three years, they can prove they have been in substantial compliance with the consent decree for nine consecutive months,” DeMuro said.

In Stitt’s press release, Friesen said the agreement marks “a significant step forward” toward ensuring meaningful mental health support for Oklahomans in state custody while honoring a commitment to Oklahoma taxpayers.

“Our priority remains improving evidence-based care and outcomes for all Oklahomans, and this agreement helps us continue that mission,” Friesen said.

Appointed to lead ODMHSAS early this year — one year after the lawsuit was filed naming her predecessor, Carrie Slatton-Hodges, as a defendant — Friesen had been scheduled to be deposed by DeMuro and his associates next week. Oklahoma Forensic Center interim director Debbie Moran also became a defendant in the case after succeeding her predecessor.

‘Once in a lifetime opportunity’

In Thursday’s third press release on the topic, DeMuro said the agreement offers “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reform Oklahoma’s broken competency restoration system.”

“We applaud the attorney general’s leadership on this critical issue, and also applaud the willingness of the governor and commissioner to sit down with us and work this out,” DeMuro said. “There’s a lot of work to do, but now we can all finally focus on fixing this serious problem.”

In a memo to leaders of the Oklahoma Legislature this spring, Drummond’s office had described the lawsuit as “indefensible” and said attempting to fight it would almost surely result in a massive financial award for the plaintiffs. As a result, Drummond and plaintiffs’ attorneys proposed a settlement involving a consent decree, which will require the state to create additional mental health restoration services while establishing and meeting new treatment standards.

In granting preliminary approval for a version of the proposed consent decree in September, U.S. District Court Judge Gregory Frizzell set a Jan. 15 hearing at which he could grant final approval if the Contingency Review Board agrees to the proposal on behalf of the state.

Members of the CRB, which consists of the governor, the House speaker and the Senate president pro tempore as voting members, reviewed a version of the proposed settlement in August and then voted Oct. 8 to reject a revised proposal. Both Greg Treat, whose term as Senate president pro tempore expired this week, and House Speaker Charles McCall (R-Atoka), whose term expires next week, could not seek reelection this year because of term limits. Their designated successors, Sen. Lonnie Paxton (R-Tuttle) and Rep. Kyle Hilbert (R-Bristow), cannot take any official action until legislators formally organize for the 60th Oklahoma Legislature, which is set to occur Tuesday, Jan. 7.

After the Contingency Review Board and Frizzell give their final approval, the parties will have 90 days to flesh out some elements of the improvement plan prescribed in the consent decree, which carries an unknown fiscal impact for the Oklahoma Legislature to address. Beyond that, state lawmakers will be asked to pass legislation permitting ODMHSAS to provide community-based outpatient competency restoration services, which have become more popular across the country in recent years.

“Within 90 days after the court enters this consent decree, defendants, in consultation with class counsel and the consultants, shall develop and begin to implement a plan, to be approved by the consultants, for a pilot community-based restoration treatment program in Tulsa County, Oklahoma County, McIntosh County and Muskogee County,” the consent decree states on Page 23.

At the end of one year after implementation of the pilot program, the consultants, ODMHSAS’ designated representative and its counsel along with plaintiff attorneys will evaluate the data, practices and outcomes of the pilot program “to determine whether, and how, a community-based restoration program may be expanded to other Oklahoma counties.” A similar pilot program for jail-based restoration services is proposed for Tulsa County and another county to be selected later. None of the prescribed pilot program services are designated for western or southern Oklahoma, the furthest areas from the Oklahoma Forensic Center in Vinita. That facility is where defendants are supposed to receive mental health competency restoration services, but its capacity has been incapable of accommodating the state’s needs for years.

“I think the real headline here is that political leaders came together, put their political differences aside and recognized that there was a problem that was adversely affecting Oklahomans, and they agreed to fix it,” DeMuro said. “They agreed to a common solution despite political differences, and that’s how government should work. I’m really proud right now to be a lawyer in Oklahoma to watch the process play out that way, because it doesn’t always play out that way.”