Being fully back in the media game means having to pay more than casual, toilet-time attention to Twitter and Facebook on a daily basis.

This afternoon, while researching for another story involving Twitter, the following tweet dichotomy caught my attention:

Ah, The Oklahoma Daily: the University of Oklahoma’s independent student voice. Not to be confused with the paper formerly known as The Daily Oklahoman.

The Daily, as it’s called on campus, will always have a place in my heart, as well as that of NonDoc Managing Editor Josh McBee. We figuratively cut (and lost a few of) our teeth there in 2006 and 2007.

Back then, however, Twitter existed as a nebulous and confusing new platform for communication. Launched in March 2006, the social media site that now boasts 500 million tweets per day was something veteran journalists and journalism students alike were trying to understand and — potentially, if the circumstances were just right — incorporate into reporting the news.

Now, Twitter is where an enormous amount of news is not only reported but often broken. ESPN personalities handle major sports news on Twitter first, with website and TV stories to follow.

But breaking and posting news on Twitter is not without peril.

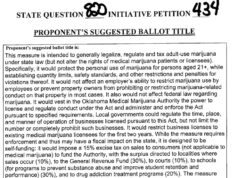

Back to 3:10 p.m. today and the story of Luke Kiron.

The Oklahoma Daily posted a story about Kiron, an OU student, being arrested a couple of days ago on suspicion of sexual battery during a fraternity party at the Diamond Ballroom in south Oklahoma City. It had been reported the day prior by multiple local television stations.

For the OU paper’s audience, any connection between an arrested student and a campus organization can be relevant and, arguably, paramount in covering such a crime story. So, Daily staff led with what they thought they’d discovered: The man arrested was president of his fraternity.

One problem: They had to correct that piece of the story 30 minutes later upon learning Kiron was a former president.

While the distinction is likely meaningless to most of the public — and certainly means very little to the alleged victim, Kiron or their families — any journalist knows you have to issue a “correction” when you publish a factual mistake.

And any journalist who doesn’t know a correction matters is going to learn pretty quickly from the actual fraternity president.

As you can see in The Oklahoma Daily’s online article, they quickly corrected the error in the story’s opening line and noted the correction at the bottom. Standard operating procedure.

But social media don’t work quite the same way, and especially not Twitter, with its 140-character limitations. As a result, The Daily chose to issue a correction that announced the error and stated the truth, and they did so without deleting the original tweet.

I direct-messaged @OUDaily to ask if, in fact, leaving the original post up along with the correction represented an intentional editorial policy.

“It is our policy to leave the original tweet up and issue a correction tweet, in an effort to be transparent with our readers,” the account administrator replied.

So while it might look odd to the average Twitter user to see an erroneous tweet remain in a publication’s feed, the idea is that a publication does not hide its mistakes or pretend it is perfect.

Not a bad policy, from my perspective.

But I learned to journalize back when Twitter didn’t have any vowels.

Here’s to thinking through the big decisions in the wild world of media, circa 2015.