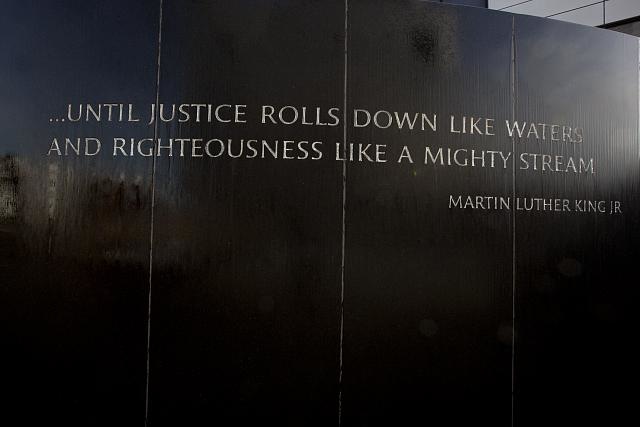

“All we say to America is: be true to what you say on paper”

— Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., April 3, 1968, at the Mason Temple (Church of God in Christ Headquarters) in Memphis

That quote above comes from a Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speech the night before he was assassinated in Memphis. It isn’t as well known within popular American culture as his iconic I Have a Dream speech. This is mostly because the dream speech was so unifying and consistent with American ideals of progress and equality, whereas the Memphis speech was hauntingly prophetic about his murder and saturated with the political violence that confronted African Americans on a daily basis. The dream speech lifted emotions around American ideals, while the Memphis speech reminded us about our dark side and confronted The System’s hypocrisy and failures to live up to what it touts.

The dream speech will be broadcast widely today, as it should. It is inspiring and seminal to our imperfect history and our painfully meted out progress. But the Memphis Mason Temple speech is a more important speech for current-day America. With our startling crises of police murdering unarmed black Americans and political candidates who make it seem like Joseph McCarthy used restraint, examining the ideals of our system and whether we are “walking the walk” is the more urgent conversation.

King uses his melodic cadences as a seasoned pastor to expose the state’s failure to provide Bill of Rights protections to black Americans at the time. “Somewhere I read, of the freedom of assembly,” King noted, and so on.

This YouTube excerpt of the speech is powerful:

Like all American children, my kids are out of school on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, a public holiday. I spend part of the day having them learn not just about King, but about the macro-level problems that gave rise to King. Of course, these systemic diseases still confront us today.

Penetrating the bubble

As affluent white boys, my children may not find much of America’s current-day crises readily apparent from the bubble within which they navigate the world. Four years ago, my then-7-year-old son’s comment took me by surprise after I had him view an Eyes on the Prize documentary segment that showed Klansmen counter-protesting in Alabama.

“Were those people made to wear those costumes in public for being bad?” he asked.

Out of the mouths of babes.

This year, my boys will watch the clip above, and we will talk about the gulf in present-day 2016 American life between “what is on paper” and what the actual practice and consequences are for different Americans, from ZIP code to ZIP code. The gulf is wide and troubling, whether it be income inequality or how my boys might be encountered by police were they to walk down a street wearing their hoodies.

And even more pernicious to look at: the gulf in how the justice system and public sector, in practice, would respond and provide proportional accountability and recompense to my wife and me in the highly unlikely event my boys were shot and killed for failing to comply adequately to a police officer’s demands. It would be starkly different than what we have seen with the likes of Michael Brown’s and many others’ families, and it would be comical if it weren’t so tragic.

Small steps of progress

The other takeaway I hope my sons get from the King clip is the courage and spiritual strength he clearly displays despite the very real danger he was facing, which ultimately ended his life the very next day. If any painfully meted out progress is to be made today on the issues I raise, my boys and I will have to show just a fraction of that courage as affluent white Americans to take simple risks in our daily lives. Risks not to our safety, but to our comfort, privilege and the system that maintains it.

As an African-American friend asked me about well-intentioned white people: “Are you all willing to decline a racist client to your law practice, or end friendships at church” by confronting those more banal racist moments we find ourselves in, where it just may be easier to say nothing and instead merely fume inside your mind?

The answer is that if white Americans who have unlearned their racism are honest, we all have had moments where we rationalize choosing our battles so as to avoid conflict or some potential fallout. Of course, many others in this country do not have that luxury of choice.

If King could find peace and resignation in the prospect that his work may get him killed, perhaps my boys and I can take some much smaller risks to our reputation and privilege, eventually helping the lot of us inescapably intertwined citizens achieve the beloved community. Small, painfully meted out steps of progress will likely do it, but they must be taken by everyone, not just those who have no choice.