(Author’s Note: The following is part two of three “sound chapters” of Oklahomans’ oral histories about race collected in Every Point on the Map’s work over the past two years. Part one can be found here. I thank all those who sat with us and so openly shared their hearts.)

The sound of black saving white

“And, I remember one, where uh, this lady,” Ray Newton, 78, of Lexington, Okla., began, “it was 100-and-some degrees outside. And this lady started to the store, Safeway or something, and had a blowout on her tire. And she had the baby in the car with her. And so, if a baby’s laying in the car, and then there’s certain exposure to all that heat.

“And so … this guy was walking … he’s a black dude, so he’s walkin’ … and this lady was trying to get someone to help her. He walked up and said, ‘First thing you need to do, lady, is get this baby outta here because of the heat.’

“And he was working for people on the same street she had the blowout on. So he took her to their house. He said, ‘Come on lady, go with me and bring the baby.’

“So he took her to the house where he was working, and he told them about the blowout and the baby’s in all this heat, so the lady said, ‘Well come on in.’ So they gave her some tea, and I said, ‘Now there’s a difference!’

“And in spite of all the references to racism and all that, this guy is nice enough, if he’s black and she’s white, to take care of her and the baby. And here’s another attitude that’s changing … because there was a lot of white females that were afraid to be anywhere close … with good reason, they had good reason, too, they’d been warned … but it’s a lot better now than it was back in the ’40s and ’50s.”

The sound of white saving black

“I was about 4, I think, and mom said, ‘Charlie, what’s going on out there?’ And he said, ‘I don’t know,’ and he looked out the window, too,” said Drucilla Martin, 89, of Grove, Okla. “What was supposed to be Black Town on the southeast corner of Cheyenne, Oklahoma — it was Black Town where all the colored people lived, and things are so different then than they are now — and mom and dad saw this person running.

“And, it was Depression, and it was hard to find food and to live … and we saw this person running. And she came down to our front yard that had a fence, and the snow was piled up against the fence. She stopped there, and dad went out and he says, ‘Girl, what are you doing?’

“And she said, ‘Mr. Charlie,’ she said, ‘I saw a rabbit and I caught that rabbit.’ And she had run all the way down in this deep snow after this rabbit until she caught it against the fence at our place. She was barefooted.

“So dad said, ‘Girl, come in and get warm!’ and he took her home with the team and wagon. He said, ‘What were you so interested in getting that rabbit?’

“She said, ‘Because we’re so hungry up there. We have nothing to eat, and we’re starving to death. We’re going to make a rabbit stew tonight. Anybody’s that’s got a potato, or an onion, or anything like that — they’ll bring it and we’ll put it in, and tonight we’ll have a big night.’

“He said, ‘Well, you need biscuits!’

“She said, ‘Oh, Mr. Charlie, we don’t have any flour. And we don’t have any milk.’ [Dru’s lips are trembling at this point, as she manages her emotions]

“So dad said, ‘Well, I have separated milk every day that I’ve been feeding the hogs. You guys can come down and get milk any time you want it. It’ll be on the smokehouse steps in this great big milk can. You just help yourselves. What’s left goes to the hogs, but you guys come first.’

“So she thanked him and he took her home and he gave her some milk to take home and he gave her some flour, so they could have biscuits that night. And my father would sneak a little bit of flour out to them with the milk, he’d put it out on the smokehouse steps.

“His woodpile was way up by the barn, and he’d find his wood chopped for our fire in the house. It was how they thanked us — they chopped wood for him. And they’d do it away from the house so he wouldn’t know. Of course he DID know — he went to chop wood and it was already chopped! Well, he knew … but my dad and mom kept them alive that winter by giving them milk and flour … I was very proud of them for doing that.”

The sounds of physical punishment

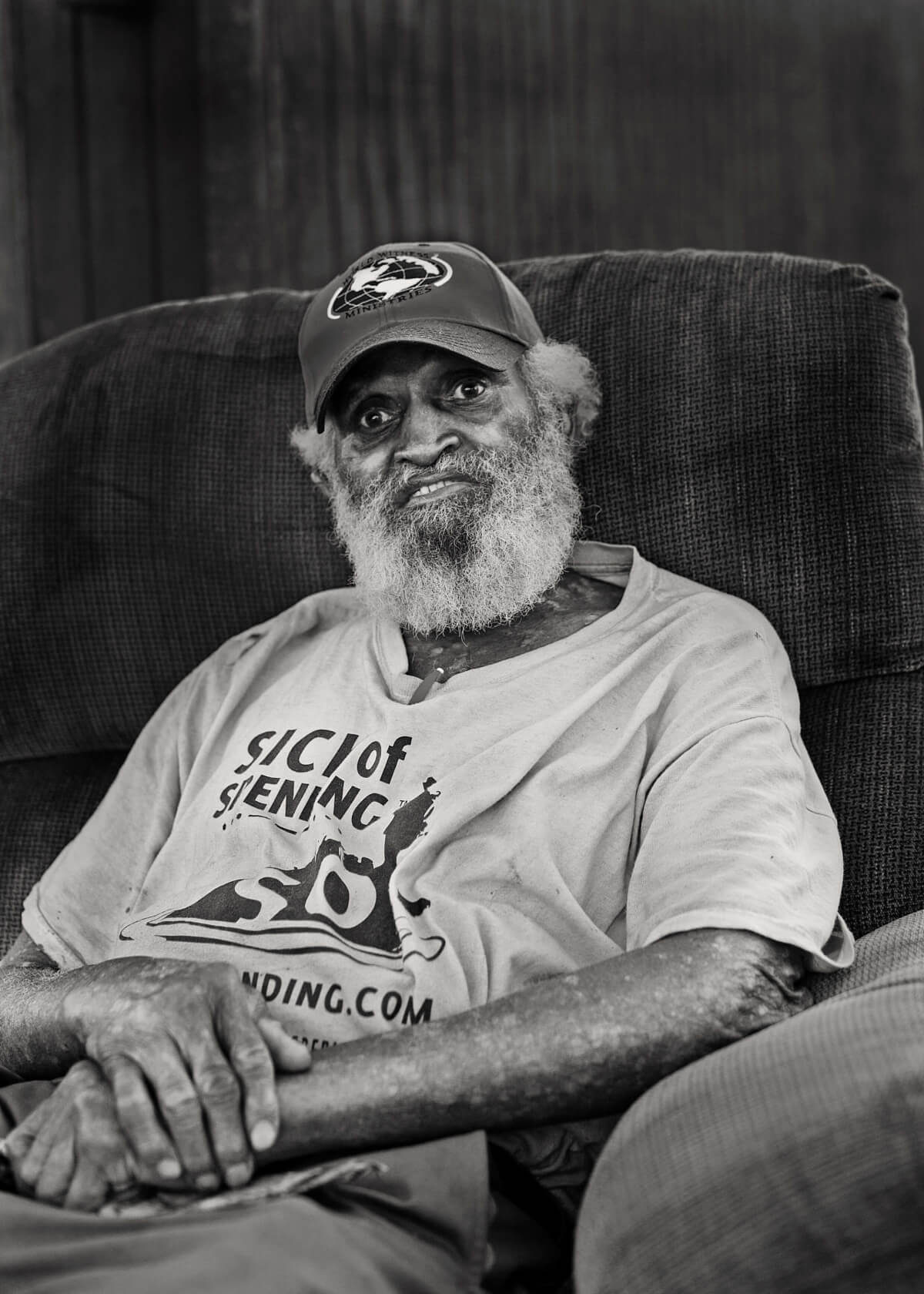

“So the worst whippin’ I ever got was from my dad,” said Cleveland Dunn, 76, of IXL, Okla. “I messed around and took some slop out the house to the hogs. We was supposed to give ‘em only corn and clear water, and I got a good whippin’.

“He wouldn’t said nothin’ but one time when he tell you to do somethin’ — next thing you know he was whoopin’ you. I had a nephew — he went to whoopin’ him and he run off, and he told my mom to, ‘Give me that 16-gauge shotgun, and I’ll stop him,’ but she didn’t get it to him in time. He said, ‘I’ll shoot him and kill him. If I done raised him, and he don’t mind, I’ll put him in the cemetery.’

[So, your dad was hard get along with?]

“No, when he say do something, he mean do it.”

[So it sounds like your mom saved the nephew’s life.]

“Yeah, my mom was as good as gold. But my dad, when he say somethin’, that means do it.’’

“Corporal punishment was alright,” said Willie Simpkins of Cromwell, Okla. “I think it still should be implemented, the ‘board’ of education. Yeah. You see those teachers up there, they drill holes in their paddles. They were made out of solid oak, not just pine — that was light — some was walnut. And they drill holes in it so they get a smooth flow. [laughs]

“It deters you from messin’ up again. But, it’s not really the paddlin’. I mean, it’s the humiliation of facing your class when you go back in there. You go in there like — not cryin’ — just looking down — looking around [at your friends] and say, “Whaddayou lookin’ at?’

“Then somebody be gettin’ a bustin’ and the whole school goes quiet. ‘Sha-POW. One. Sha-POW. Two. POW! Three. Okay, that’s all they gettin’ — three — well, they must’ve not messed up too bad … ’ When they get five or six, it was rough.”

ORAL HISTORIES SERIES: PART ONE

Recalling racism with oral history: resentment, tension and change by Kelly Roberts