One year ago today, a media circus descended upon the University of Oklahoma after video of a racist chant by a top-tier national fraternity member went viral.

A year later, Sigma Alpha Epsilon no longer has a chapter at OU, but the ripple effects of the fraternity’s fatal moment are still felt campus wide by those paying attention.

In a broader context, the naked bigotry conveyed by the hateful chant surfaced March 8, 2015 — early in the same zeitgeist as a 2015-2016 presidential season full of ugly and sometimes xenophobic rhetoric.

The chant leaders from OU’s SAE party bus were caught red-handed in the digital world, and they were forced to make their public apologies known: Levi Pettit, alumnus of the Dallas Jesuit, stood next to African American leaders at a public event, looking alternately bored and nervous, young and exposed.

The aftershock at OU testified to stronger secret agonies among students. A public forum held at Price Hall and organized by OU Unheard — the African American activist organization that had first acquired the shocking video via an anonymous source — took a stab at making progress.

A variety of students came. From quiet, nerdy freshmen — intrigued and pissed — to rows of African American sorority members humming, “Mhmm, yes,” as a business major, Naome Kadira, told the Price College of Business dean about being a first-generation black student who is passed from adviser to adviser in the college.

An Iraq war veteran named Tyrell stood up: “I’ve been harassed by police, even when I’m in uniform. This is the first time I’ve been back to Norman in three years. I’m ashamed to come back. They judge me on site.”

The mood of the room wasn’t electric with anger. Rather, it was mournful and faintly cathartic.

Few mentors on campus

OU anthropology professor Betty Harris instantly pushed the event into her courses, “Race and Ethnicity” and “Women and Development in Africa.” She described the subsequent year’s discussions between students as fluid, and, like the demonstrations following the SAE video’s publication, civil and dignified. Sometimes, she met with certain students after class.

“They were sensitive to the issues and concerned with what happened,” said Harris, speaking about the topic in 2015. “Often times when these things occur, minorities are put on the spot and are the focus of it. Even though Unheard and no minorities actually initiated it, they are blamed for creating an atmosphere in which it could occur. I think the students know they are expected to engage with these issues.”

Harris, an African American whose father was faculty at the Tuskegee Institute, has taught in Norman for more than 30 years. She said there were very few black people when she moved there in 1967, a sentiment echoed by OU professor emeritus George Henderson in a recent Norman Transcript article.

One of the grievances listed in an open letter by OU Unheard two months before the SAE video was a lack of mentorship and role models for minority students (e.g., 2.17 percent of faculty is black). In her early days at OU, Harris said she did more faculty mentorship for African American students, writing letters of recommendation for seven to eight students a year. She attended Black Student Association events that were held at the beginning of the year to refer services to new students. As the number of black students attending OU decreased, she said she has had fewer in her classes.

The day the SAE scandal erupted, Harris was in the historically all-black town of Boley with a graduate student. Since the neighboring town was all white, Harris said the dichotomy gave her a sense of dimension that day. The separation was stark, and she found the playful manner with which the SAE members referenced lynching to be troubling.

“I am over 60, and growing up in the South, lynching wasn’t occurring,” Harris said. “There were murders that weren’t prosecuted, but I heard stories about lynching from my parents and grandparents.”

Though always welcomed in Norman, Harris noticed things that contradict her earlier ideals about college life.

“I had a more hospitable and supportive introduction to OU,” Harris said. “Certainly at the time, I thought it would become a more multicultural environment in which there would be all kinds of interactions — more of the development of a multicultural intelligentsia — and that hasn’t happened.

“I’ve seen a lot of people come and go in that period. There were some tenure denials, and some people just left. That has been an issue — an ongoing issue of concern — and a sense of incompleteness with regard to my perceptions of what [my time here] might have been.”

A difficult conversation continues

Only two years earlier in 2013, Washington University in St. Louis students had merely been suspended after a similar recording emerged. Wash U’s vice chancellor “opened an investigation,” and pledged to reach out to student leaders.

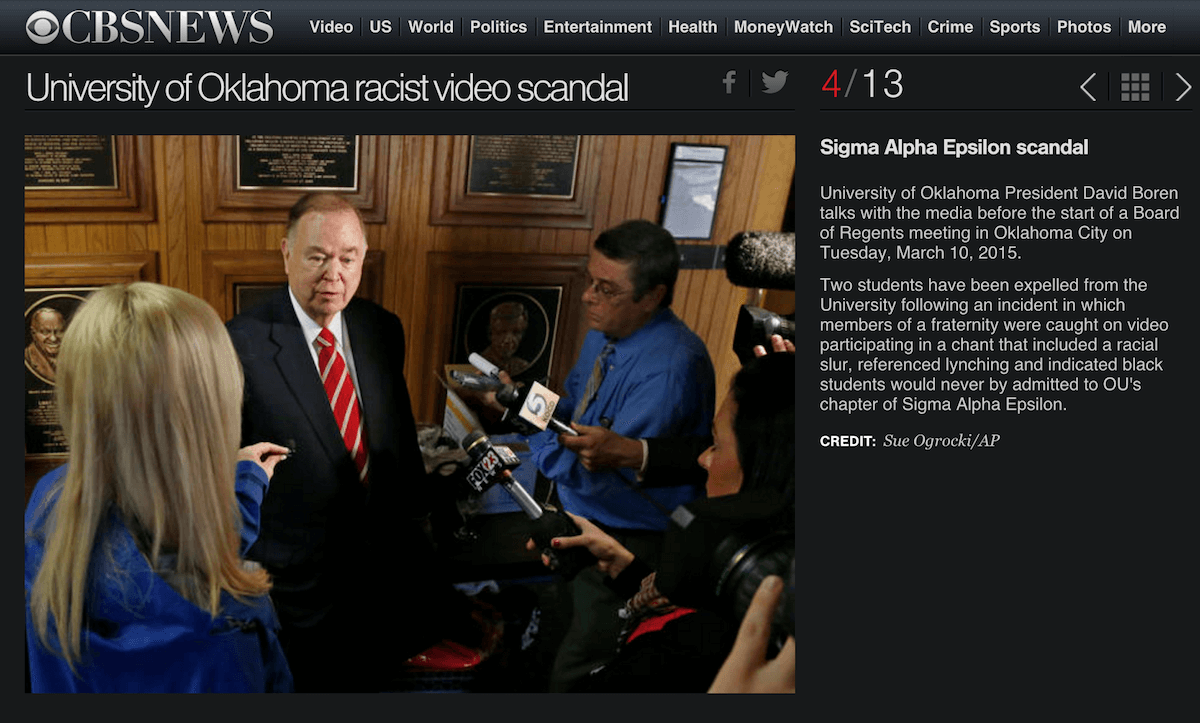

In contrast, OU President David Boren took unusually swift and forceful action when he moved for the expulsion of the primary SAE offenders and shut down the campus chapter in 2015. Boren directly called the fraternity house “disgraceful” two days after the OU SAE video emerged. The former governor and U.S. Senator addressed the awaiting media firestorm head-on, taking great public offense at the fraternity’s behavior while legal scholars debated the First Amendment’s allowance of Boren’s disciplinary actions.

“I would handle it again exactly the way I did handle it,” Boren said to NonDoc in a statement last week. “There are moments when you simply have to do what you think is right without worrying about any potential consequences. I believe strongly that the only way to stop racism in America is to have zero tolerance for racism whenever it is expressed.”

Earlier this year, the national SAE organization’s internal investigation revealed that the chant had been expressed in five of its chapters.

At OU, meanwhile, Boren hired and introduced a vice president of diversity, Jabar Shumate, who in turn spearheads the diversity and inclusivity programming now offered at Camp Crimson for incoming freshmen. The training is also included in the university’s Gateway to College Learning courses.

Those courses aim to help students identify explicit and subtle ways group differences exist on campus and in society, and instructors introduce students to the ways each student forms his or her identity along race, gender, ability, sovereignty and class lines.

Boren said the student reviews of the course have been overwhelmingly positive.

Chelsea Davis, a pre-med junior and leader of OU Unheard, has facilitated the meetings and said many students are nervous and don’t want to say the wrong things.

“If you’re comfortable, then you’re not changing,” Davis said. “In order for people to have these raw conversations, they have to step out of their comfort zones and realize they have to recognize that something needs to change. They don’t want to confront their own privilege. It’ll start when people look at themselves and say, ‘What am I doing to hinder diversity and inclusion?’”

Meanwhile, a group of campus Republicans believes the OU diversity course punishes people who aren’t diverse enough and feel uncomfortable in the classes.

“I feel that, at the college level, feelings are going to be hurt,” Kyle Meyer, an OU College Republican told The OU Daily recently. “If you unintentionally hurt someone’s feelings, you should apologize and move on about it.”

Arguments to “move on about it,” however, can seem tone deaf and lacking in perspective.

Tara Evans, a women and gender studies major, became involved in discussions and events with OU Unheard after leaving her sorority at UCO and transferring to OU. Often, when she would try to “raise awareness” as a white person among her friends in OU’s National Panhellenic Council, people would ask why she was speaking out about it. She called it “negative feedback.”

But contrary to the “move on about it” philosophy, Evans said she examined her place in the college ecosystem, partly due to classes she was taking. She has taken Harris’ classes and now plans to work with survivors of domestic violence after graduate school. As a sorority member, she can remember taking anti-Greek sentiment personally because she had put a lot of her undergraduate efforts into the organization.

“Now I know UCO and OU are definitely predominately white institutions, but when you are white, that wasn’t something I actively thought about until it was taught to me, and then I had to think critically about it,” Evans said. “The thing that changed after seeing this thing break out was, I had more empathy for people who weren’t white, and (I was) taking more of a critical look at myself.

“There was no reason for me to think about it before. … I knew what my experience was. I’m from a sorority. But hey, maybe I should just listen to other people and what their experiences are instead of assuming they should feel a certain way.”

‘I wouldn’t say SAE was disproportionate to the general population’

A former SAE house resident who graduated in 2012 and asked to speak on condition of anonymity in 2015 said he was never taught any racist words or chants as a fraternity member and that the characterization of SAE as racist was unfair. He said the media placed too much emphasis on an “idiot’s” actions.

He argued that the racism he encountered seemed to be more ingrained culturally and less about actual hate.

“I would really like to say that, yes the feelings [of the chant] surprise me,” he said. “But while at OU, I met a bunch of ‘cowboy’ types who had no real problem with black people, yet would tell racist jokes, etc.

“I wouldn’t say SAE was disproportionate to the general population with regards to this attitude.”

When Greek groups reached out to the Black Student Association for the 2015 homecoming, Chelsea Davis said the racial divide appeared along economic lines in that moment.

“When we were sitting at a table, they paired BSA [Black Student Association] with three or four Greek [houses],” Davis said. “They start to ask, ‘How much money can each organization contribute?’ and IFC can present $2,000, and BSA can give $500, if that. It’s an issue of a lack of funding. Because we don’t have houses, it’s hard to participate in floats.”

On campus, Davis noted a literal separation, with black fraternities having their events at the student union or the Henderson Tolson Center in the absence of pillared, leafy fraternity houses.

Like many cultural commentators, the former SAE member agreed that not many steps have been taken since the Civil Rights era.

“Racism just isn’t taboo enough yet,” the former house member said. “The problem won’t be solved on a fraternity — or a student-level. There has to be a shift in society to prevent this. How do you make society as a whole shun ignorance? You’ve got me there. Honestly, I think a reggae fest would be more effective than any institutionalized system.”

Still Unheard

OU’s campus activity council did try to reach across the aisle this year with a concert (albeit not reggae). OU Unheard’s early complaint was that the $159,000 budget for CAC dwarfed the Black Student Association’s $7,000 budget, a fact that had many black students traveling to Denton, Texas, for better concerts and a more vibrant culture, Davis said.

As a result, the Campus Activities Council and the Union Programming Board brought the rapper YG to campus, but it was not without controversy. The groups initially conducted a poll on Facebook to see what artist to invite, but students noted that they didn’t talk to the Black Student Association directly about who to bring.

When YG arrived, he was asked not use any version of the N-word.

“The effort is there, but it’s not working,” Davis said. “The way CAC and UPB goes about it, it’s with disregard to black culture and minority culture. They didn’t want white people in the crowd to feel uncomfortable because they couldn’t say it. Well, the counter-argument would be that black people are uncomfortable in white spaces every day and deal with it, so white people can be uncomfortable in this space.”

In a silent way

After the SAE scandal, prayer groups gathered around OU’s campus to try to bring a more healing ambience to Norman. It was a quiet procession, punctuated by Unheard members with tape over their mouths (symbolizing muted voices in the dominant culture) and their walk to administrative offices to post notes with their thoughts written on them.

OU Unheard, led by Davis and others, earned a following in the age of hashtag activism and Ferguson. The appeal is often moral and influenced by the Christian faith, as when Unheard voiced support with The University of Missouri, which erupted in protest after the student body president reported being called racial slurs and swastikas were found on campus. Ultimately, the university’s president resigned. Unheard, both nationally and locally, replied with their trademark taped-over mouths and #PrayforMizzou.

‘Whole new territory’

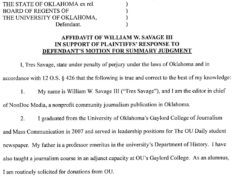

Back at OU in 2016, Chelsea Davis is a first-generation college student. Her plan is to become a doctor, though an interest in social justice was sparked after evenings spent with the Unheard group, deciding whether or not they were going to release the found video, which ultimately launched a few of the undergraduates onto the national media platforms of MSNBC, CNN and other networks.

But Davis and her friends speak from a college environment with more challenges than just a racist chant that came out of left field 365 days ago. Like many a strained college student, they adapt to navigating work and school, finding a decent standard of living or weathering the transition from an inner-city classroom to a competitive lecture hall.

Working two jobs and being active in high school helped Davis prepare for the stresses of college, but the specific experience is something she’s learning entirely for herself.

“My mom went into nursing, and dad was military, so I’m a first-generation (student) and the oldest (sibling) in my family,” Davis said. “It’s whole new territory for me and my family.

“You really don’t know what to expect as a student. Me, I really didn’t. I didn’t ask mom and dad, ‘How does this work?’ We all kind of figured it out. It was a learning experience for all of us. I have two younger brothers. Scholarships, finances, how do we pay for school?”

With one-year down of post-SAE life at OU, Davis said she feels more mature.

“It’s definitely been a learning experience — year by year.”