For all the variegated multiplicity of its forms, the practice of sacrifice can be reduced to two gestures: expulsion (purification) and assimilation (communion). These two gestures have only one element in common: destruction.

— Roberto Calasso

In the United States, it’s the job of “the paper of record” to support the country’s wars. Lyndon Johnson knew this when he said of Vietnam, “I can’t fight this war without the support of The New York Times.”

Sometimes, if the fourth estate is expected to check and balance the powers that be, it can’t look like it is supporting a war — especially a controversial one.

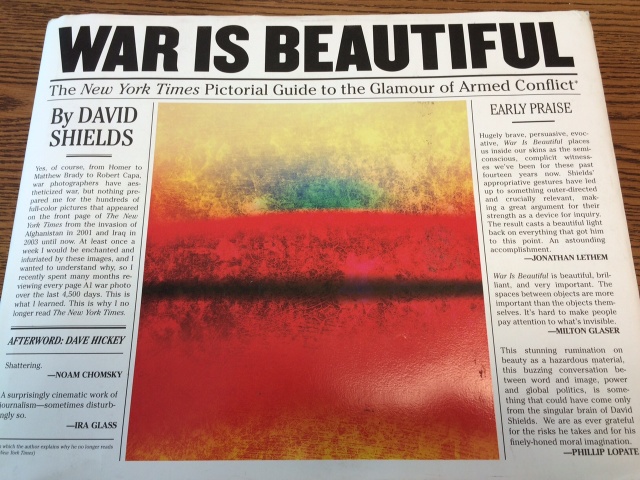

Bestselling author David Shields approaches these truths sideways in his mock coffee table book/collage War is Beautiful. It’s a kind of art project aimed at speaking truth to power. The result has a surprising effect; Noam Chomsky calls it “shattering.” Another, more unintended effect is that, in December, the New York Times sued the book’s publisher, Powerhouse Books, for copyright infringement.

A novel for the Twitter age

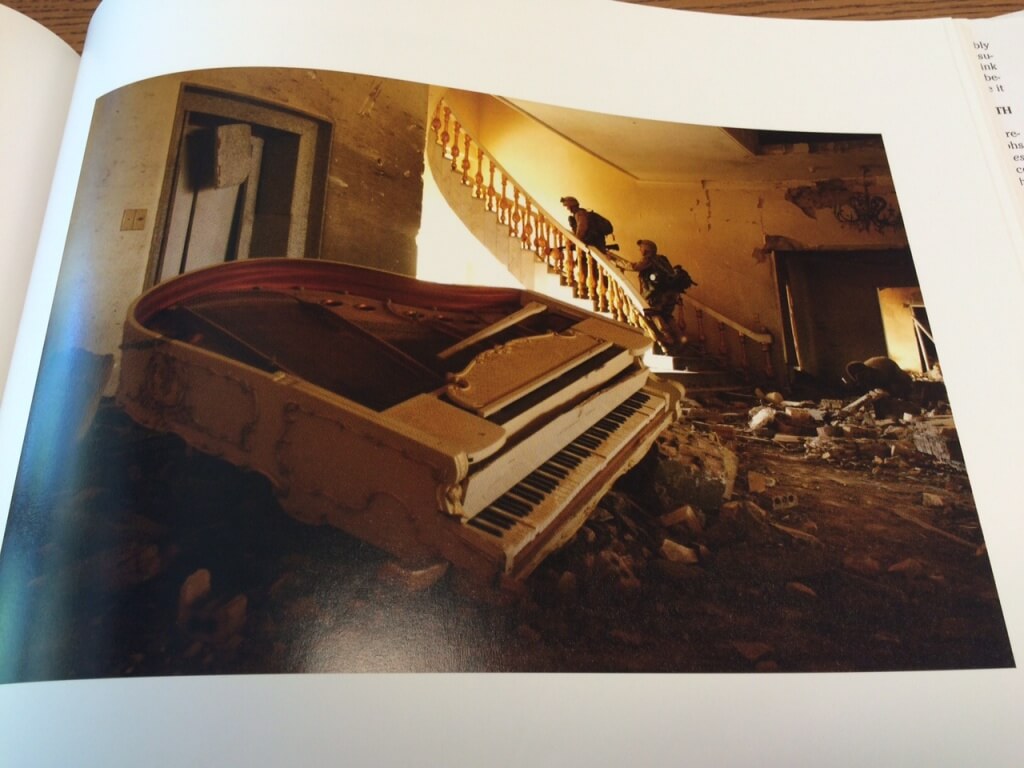

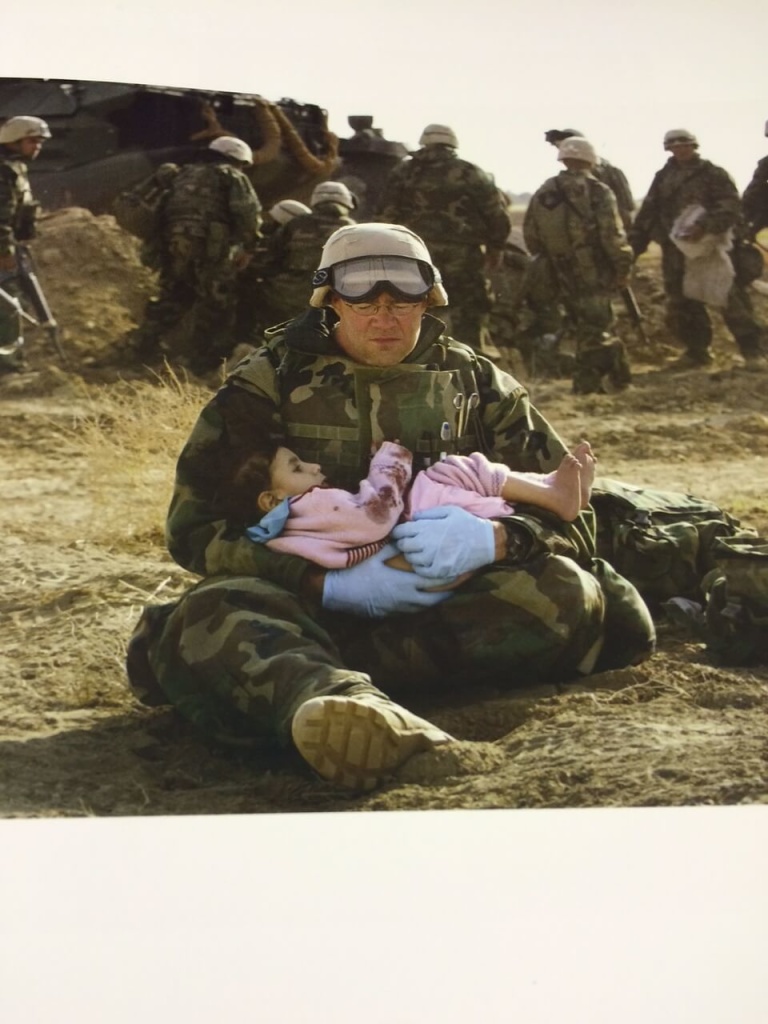

For Shields, every moment is a chance for found art. In his previous book, Reality Hunger, Shields shed light on his artistic education. He wanted every second to be an aesthetic moment. By keeping this mindset over time, he discovered that after decades of contemplating the front page of his morning Times, the apprehension of beauty invited a feeling of horror, too. The pictures used by NYT for the Afghanistan invasion in 2001 and then the Iraq war in 2003 were so well-composed and rendered (to the point of abstract expressionism, if needed) that the motifs and artfulness in the pictures had to mean something.

In Reality Hunger, Shields argued for a new nonfiction writing to displace the novel in the Twitter age. In War is Beautiful, Shields has realized his goal without stealing as many quotes, and he refrains from excess editorializing or simply rearranging the NYT’s war photos. A writer who typically rants until he’s blue in the face does very little writing here (apropos of the meme age) to make a powerful statement. War is Beautiful also suggests that maybe 95 percent of the country’s elected and self-elected truth tellers — journalists and writers — do not see what’s going on.

In the afterword, art critic and writer Dave Hickey reminds us that a Times photo is touched by the photographer, the photo editor, the managing editor, the section editor, the page editor, the designer and the layout person. You see a framed idea, not something happening in messy reality.

Critiquing a newspaper’s subconscious

Through meticulously annotated photos, War is Beautiful presents the newspaper as partners with the American military. One can’t exist without the other. The photos lend a beauty and credibility to a war that Shields still finds obscene (“behind these sublime, destructive, illuminated images are hundreds of thousands of unobserved, anonymous war deaths”). Shields finds everyone responsible, an idea invoking the long-lost public-intellectual credo of Jean Paul Sartre: that a writer, or artist, should be engaged with his times and also take personal responsibility for the society in which they live.

“Over time,” Shields writes, “I realized that these photos glorified war through an unrelenting parade of beautiful images whose function is to sanctify the accompanying descriptions of battle, death, destruction, and displacement.”

Shields dared to critique what may amount to a paper’s subconscious. As images and out-of-context sounds begin to dominate our news feed and distraction loops, there’s a machine at work behind the making of a story. A consequence of the image overload will be a diminishing of our ability to analyze images beyond their surface. Shields is positing that there are stories we are trying to tell ourselves.

The ongoing disruption of war

Whether you agree with Shields or not, Farah Nosh, an Iraqi photographer quoted here who worked for The Times, speaks to the disruption that is now spreading across a hyperconnected globe, whether it’s violence in Paris, France, or Chris Kyle’s backyard. The damage was done and is being done.

“The family I know in Baghdad … are not the same family I met when I first arrived,” said Nosh. “The family structure is the most important thing in our culture and when that’s disrupted, nothing is the same. The family structure has been hugely disrupted in Iraq. The degree of post traumatic stress is something that we’ll never even begin to comprehend.”

(Correction: A previous version of this article erroneously referred to a lawsuit that has not actually been filed.)