AUSTIN — Saturday in the tech capital of Texas, citizens voted to drive out popular ride-sharing services Uber and Lyft. Monday, Uber and Lyft suspended operations in Austin.

When the City Council approved regulations last December requiring fingerprint-background checks for transportation-network companies (TNCs), Uber fought back. First, the company threatened to back out of Austin, one of the most congested traffic cities in the U.S. Then, it filed Proposition 1 in an attempt to eliminate the fingerprint-background check requirement. Prop 1 failed Saturday.

Lisa Schneider, a lifelong Austinite and a violin teacher to adult beginners, participated in early voting.

“It’s a waste of our money to have to do this,” Schneider said, “a waste of people’s time and energy. There’s another run-off election at the end of May. That just makes me mad. I’m not against Uber and Lyft as entities. I think they can run their business in different ways. Basically, they just need to follow the law, and they are being whiny crybabies about it. They left San Antonio.”

New tech, new problems

On Friday morning, NonDoc spoke with Mykle Tomlinson, campaign coordinator for Our City, Our Safety, Our Choice, an organization in favor of fingerprint-background checks.

“We don’t want Uber and Lyft to leave,” Tomlinson said. “We like ride sharing. We think that they should play by the rules. The rules were made by the democratically elected City Council, and then [TNCs] came out and wrote their own rules. That’s why we hope they will come back to the table and negotiate again.”

Our City, Our Safety, Our Choice speaks to the core of Austinites’ skepticism about corporations arriving and changing the policies of a city. Grassroots efforts have in the past sought to protect the waters of Barton Springs from development. In another trend, tech companies now come to Austin with a jobs-for-incentives game plan. In one case that angered residents, Intel began building downtown with the help of $2.56 million in waived fees. They left a 10-story skeleton there, though, when they stopped selling as many microchips. Saturday’s vote on the latest ubiquitous start-up that’s revolutionized travel could be Austin’s way of saying, “Enough.”

At Our City, Our Safety, Our Choice, there were over a 100 volunteers but significantly less financial backing ($120,000 vs. the staggering $8.1 million donated to Ride Sharing Works for Austin, Uber and Lyft’s political action committee). To the last minute, UT students and Austin natives had phone banks rolling, volunteers block walking, people sending emails and posting on Facebook.

At the time of our interview, Tomlinson was reading an article in the Austin American-Statesman documenting a revision by the police of DWI numbers, from 16 percent to 12 percent. Both the organization and the papers never stopped cramming for the vote on Prop 1.

Uber spokesperson Debbee Hancock had countered to the press that the company offers something essential and refreshing to an overcrowded downtown area west of a treacherous I-35 — a city with a traffic problem. She argued to Watchdog.org that Uber has generally established a good safety track record:

“Austin,” Hancock tells me, “was an early adopter. Since then, 500,000 people have gone to our app and requested a ride. And since this ordinance has been proposed, 30,000 people have signed our petition to keep Austin Uber.”

One facet of the debate came down to convenience versus civic principles, and even labor.

“While I understand there’s problems with unions, this feels like an attempt to union bust, really,” said Eric Vormel, a web project manager who has lived in Austin for 30 years. “Uber and Lyft both, and other transportation companies, treat their employees [poorly]. They supply their own cars. Get paid $10 an hour. No health insurance.”

Tomlinson said that the referendum, which cost the City between $500,000 to $800,000, doesn’t have anything else on the ballot for a vast majority of the state.

Then you have your residents who have seen a city transformed by the tech industry and other incoming masses in search of a new, L.A. kind of town — a different town, of which Uber is a symbol.

“Maybe if they leave, some of the people will leave,” said Austinite Missy Carugati.

Another Austin resident, John Gilchrist, strongly agreed with the city. At first, he supported Uber, which operated its first four months in Austin illegally, but things change after a criminal charge is filed, and then the city becomes liable, Gilchrist said. A variation on the idea could be, “Would you let your daughter or sister get in the car with a person if you didn’t 100 percent know it was safe?”

“If they can meet the city of Austin’s requirements then they can do business here,” said Gilchrist. “If not, then people will have to wait a few more minutes when they call a yellow cab.” Talking about the issue at Cherrywood coffee shop, he said the TNCs should comply with the city but also that the taxpayers and the city shouldn’t have to pay for the background checks.

Uber and Lyft stir complex debate

The conversation has been filled with detours and complications. The city initially moved when individuals and a women’s abuse shelter reported seven claims of sexual assault at the hands of TNC drivers. In November, Uber’s general manager fought back and sent a memo to the mayor, claiming “when 163 drivers with Austin cab driving licenses applied to Uber, 53 of them failed the background check — 19 after Uber found serious offenses like felony assault and DWI on their records.”

Then, the police department came out in clear opposition to the city council in December. Sheriff Greg Hamilton issued a statement — challenged in a pre-referendum Statesman article– in which he said the number of DWI arrests decreased by 16 percent in 2014. Uber and Lyft set up shop in 2013. Police Chief Art Acevedo echoed that the biggest danger would be for the city to lose 10,000 options.

Those against Prop 1 said the current name-based background check isn’t rigorous enough. The current safety check entails:

- Displaying each driver’s name, photo, license plate number and a photo of their vehicle in their profile

- Every trip is GPS-tracked

- Riders can ping those waiting for them their exact location in real time and send an estimated time of arrival

- Drivers and riders can rate each other after each trip

- Uber coordinates with law enforcement where needed

Ridesharing Works for Austin, Uber and Lyft’s PAC, put up an unprecedented amount of advertising might to nail one message into voters’ skulls: The taxpayers will shoulder the cost of the fingerprint-background checks. Their ads seized on the uncertainty of the council’s payment plans for the background check. One ad featured a voice-over saying Austin taxpayers would pay for the checks.

‘Uber has been a lifeline’

I moved to Austin in February and immediately grasped the convenience and spread of Uber’s influence.

At a family funeral, I met a man who spoke without wanting to be sourced. He lost three brick-and-mortar locations for his furniture store. Into retirement age, he’s found he could make enough income driving with Uber to make ends meet. Driving also makes his life more interesting with clientele ranging from foreign-born riders to UT students out on the town.

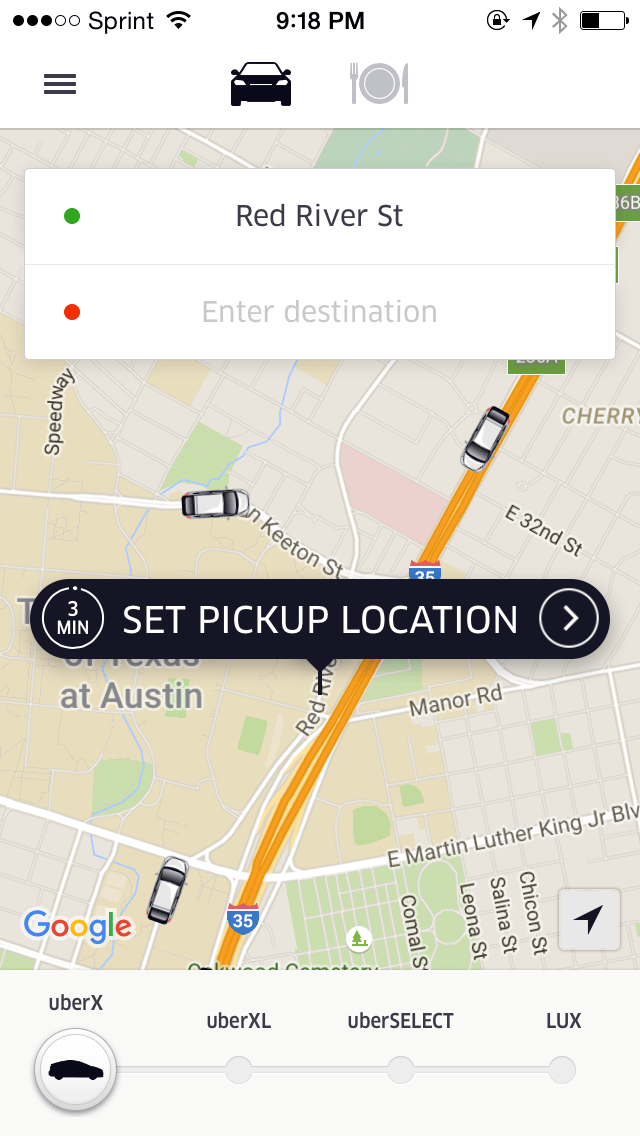

For employees like him and my Uber driver during the SXSW conference, Uber has been a lifeline. James Reeves picked me up on Red River street at 2 a.m., when SXSW traffic looked like a bed of lava stretching to I-35. Reeves got us on the highway northbound in under five minutes.

— Danny Marroquin / NonDoc

The argument can be made that it’s not asking much of a contract driver, if they want to work, to pay $40 for a background check. Substitute teachers and taxi cab drivers, for example, already pay for their own background checks. In Houston, Uber drivers already submit to a fingerprint-background check.

The Austin American-Statesman reported that, while the council hasn’t figured out specifics, the current ordinance establishes a 1 percent fee on ride-hailing companies’ local revenue to pay for it. If that money doesn’t cover the cost of fingerprint checks, the city currently can raise those fees to the state maximum of 2 percent or require app drivers to pay.

A new way of living

From the City Council to Tomlinson’s organizers, no one truly wants Uber and Lyft to leave. So, this may simply open the door for changes in tactics for a company that has become part of a lifestyle, and now, an essential part of the world economy.

TNC driver James Reeves has been reading in-house emails from Uber that speak to the lobbying efforts of the taxi cab groups here. Uber cited 163 taxi cab drivers that were previously guilty of crimes ranging from DWIs to hit-and-runs to domestic violence who had failed to pass Uber’s background check. Reeves also said that the wait time for drivers to receive a background check in Houston has been four months, a period in which a full-time Uber driver can’t afford to be sidelined.

“If Prop 1 fails, now I have to find time out of my school schedule to go to downtown Austin to get the fingerprint done,” Reeves said, “and then the wait four months before I start driving again. So it would be a big financial hit to me. There are plenty of people that are operating Lyft and Uber, and some, it’s also their sole source of income. So you are putting a good portion of people out of their jobs and who won’t be able to provide for their families.”

Now, Reeves may have to wait even longer.