CHAPEL HILL, N.C. — When I was in college, I took a class on race and southern politics, which is where I learned about the turbulent and often bizarre history of congressional district gerrymandering in the Deep South and beyond.

My professor, Keith Gaddie, told the story of a lawmaker who bragged that the shape of his oddly drawn congressional seat allowed him to open both car doors on the interstate and “hit every person in the district.”

That story stuck with me because the image it invoked was absurd and downright outlandish. Moreover, the story came straight out of the early ‘90s, which meant we could all shake our heads and say, “Well, at least we know better now, right?”

Not so fast. Roughly six years later, it hit me: That story was about a congressional district in my newly adopted home of North Carolina, where a recent lawsuit had just been filed to challenge the 2011 congressional district maps drawn by a Republican-led legislature that came to power in 2010.

Evidently, we did not know any better.

Fast forward to 2016: Things are still a mess, and it seems like it’s only gotten worse. Tuesday, North Carolina voters went to the polls for a second round of primary election races. Our state’s “official” primary had been held March 15, but a series of recent events stemming from the aforementioned 2013 redistricting challenge necessitated that the state hold a second primary to determine congressional candidates and one N.C. State Supreme Court seat up for election in November.

Redistricting drama

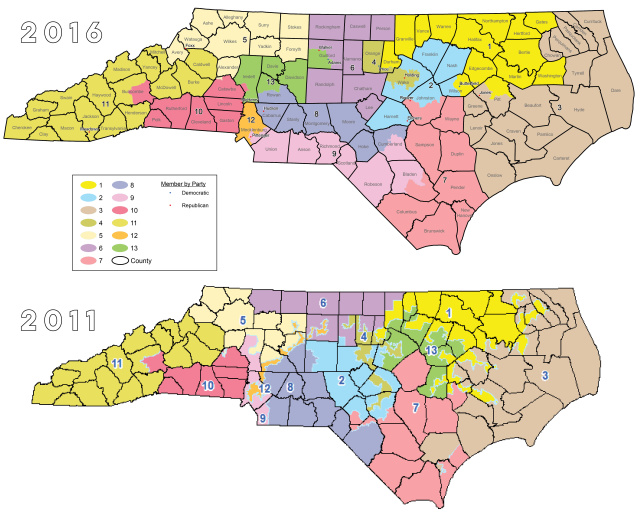

North Carolina’s latest redistricting drama began in early February when a federal district court invalidated maps for two of North Carolina’s 13 congressional districts — the 1st and 12th — on the basis that they were products of unconstitutional racial gerrymandering. The three-judge panel then gave the Republican-led North Carolina General Assembly two weeks to redraw the district lines and submit the new maps to the court for consideration.

Drawing the new congressional maps meant that legislators had to pass another bill to move the state’s congressional primaries to June 7. In the midst of the redistricting debacle, the state asked the United States Supreme Court to issue a stay of the lower court’s ruling, which would preclude the need for a second primary date. Without explanation, the Supreme Court denied the state’s request, and the state continued with plans to move forward with the second primary date.

To complicate matters further, North Carolina residents had already begun returning their completed absentee ballots ahead of the primary election scheduled for March 15. Moreover, because primary ballots had already been printed, election officials went ahead and encouraged voters to fill out their entire ballots anyway.

Frustrated yet? It just gets worse.

New maps, old incumbents

Legislators voted along party lines to pass new district maps that forced major changes to 11 of North Carolina’s congressional districts. Most notably, the new maps drew the state’s 13th Congressional District into the 2nd Congressional District, which had the practical implication of pitting two Republican incumbents (U.S. Reps. George Holding and Renee Ellmers, respectively) against each other.

It’s no secret that Ellmers has had a target on her back for some time, and GOP leaders deftly used redistricting to get rid of her without having to go through the trouble of actually organizing an angry mob carrying pitchforks (who has the time, really?). Slate wrote a piece about “how Ellmers became a GOP villain.”

Other implications

With the 13th district conveniently vacated of any incumbents running for office, the race quickly ballooned to a field of 22 total candidates, including 17 Republicans and 5 Democrats. (The Raleigh News & Observer dubbed the race a “spectacle.” Indeed.)

What’s more of a political extravaganza than a field of 22 candidates seeking one seat? Well, this: When legislators moved the congressional primaries to June 7, they also included a provision to eliminate runoff elections this year. (In regular election cycles, a second primary is held if no candidate garners at least 40 percent of the vote.) So, whomever gets the most votes will automatically win, thus making the primary stakes somewhat high.

Election day and the true cost of the primary

Obviously, nothing about North Carolina’s second primary has been cheap. Outside groups reportedly spent $1.2 million trying to influence the Holding-Ellmers primary alone. The N.C. State Board of Elections estimates that the total cost of the June 7 primary will be well over $9 million.

Anyone who’s been involved in an election knows how difficult it is to keep the voting public interested, and this protracted redistricting battle has undoubtedly done little to engage those who don’t enjoy following this kind of thing on a daily basis. According to the N.C. State Board of Elections, just 7.6 percent of the state’s 6.6 million registered voters actually cast a ballot in Tuesday’s election.

As the night closed, Ellmers had been ousted by Holding in the 2nd district. In the 13th district, the runoff-free primary meant the GOP and Democratic winners prevailed with only 20.2 percent and 25.7 percent of their respective votes. For the Democrats, Marine Corps veteran Bruce Davis topped totals with 4,694 votes, and gun store owner Ted Budd won the GOP primary with the support of 6,127 voters.

What’s next?

Is this redistricting conflict a new problem for North Carolina? Certainly not. North Carolina has a interesting history when it comes to its redistricting issues, specifically with the 1st and 12th Congressional Districts. (The latter has been cited by the Washington Post as the most gerrymandered district in the entire country.)

So, what’s being done to fix this?

Most recently, a coalition advocating for redistricting reform renewed the push for lawmakers to create an independent commission that would oversee the maps for congressional seats and state legislative districts. While some lawmakers scoff at the idea of an independent commission, both Gov. Pat McCrory and Attorney General (and Democratic gubernatorial candidate) Roy Cooper have said they would like to end gerrymandering. While the call to “end gerrymandering” is overtly and perhaps intentionally vague, it’s hopefully the beginning of something more substantive.

The alternative, I suppose, is to see how much money we can waste while alienating as many voters from the process as possible.