(Editor’s note: **Spoiler alert** … A few key points and surprises of the film Tower are revealed here.)

There were many fun films and opportunities to party at this year’s deadCENTER film festival, but no moment quieted a room like Keith Maitland’s Tower, an animated documentary and narrative recreation of the 1966 sniper massacre on The University of Texas campus.

Unbeknownst to anyone at Saturday’s screening in the OKC Museum of Art’s theater, the film was being shown less than 24 hours before a man with an AR-15 assault rifle walked into a night club in Orlando, Fla., and committed the worst act of terrorism on American soil since 9-11, with 50 people dead and 53 wounded.

Nevertheless, the film screened again Sunday and prompted thoughtful question-and-answer sessions afterward with Maitland, the director, merely hours after many in attendance learned about the Orlando shooting.

Director: ‘Same thing over and over’

“Even what happened today, it’s intense,” Maitland said, during an interview Sunday in the aftermath of the shooting. “You know, I think most people — when they see these kinds of events on the news, they shake their heads, and then they change the channel.

“We all take a moment to stutter and stumble through a reaction. Nobody that I’ve ever met thinks that the situation that continues to replay itself in the shadow of ‘the tower’ is a sustainable or acceptable kind of way to live, as a society. But nobody seems to know what to do about it.”

That goes for Maitland himself.

“I also don’t know what to do about it exactly,” he said. “But I thought we could examine this shooting, the first of its kind, and benefit from the 50 years that have passed to see the impact on Claire and Martinez and McCoy and Artly and all these people, not just on Aug. 1, 1966, but today at 50 years later.

“And that’s what separates (the tower shooting) from Newtown, and Columbine, and Orlando. It’s the only thing that separates it in my mind. They are all the same exact thing over and over again, but we have the benefit of time and perspective on this one. What that benefit gives us, I think, is up to the audience.”

“Every Q and A I do someone asks, ‘What can we do to stop these shootings?’ And I tell you, if I knew what to do to stop these shootings, I wouldn’t have made an animated movie about shootings. I would be stopping the shootings,” Maitland said. “But I don’t know. My responsibility ends when the light hits the screen. At that point it becomes the audience’s responsibility to take what we’ve given them and go do something with it.”

The expression has made its point nationwide. Former Today Show mainstay Meredith Vieira is an executive producer of Tower through the production company she started in order to make films that dealt with social issues. Maitland said he was surprised when Vieira’s rep, Amy Rapp, approached him last year while he struggled to complete his budget.

‘Something amazing happened’

The first 50 minutes of the film occur as an approximate real-time immersion in the day’s events 50 years ago through the perspectives of seven characters: police, a book shop owner, victims and witnesses. This part of the film successfully pulls off what Variety darkly but aptly called “an expression of nostalgia for the days when a mass shooting still had the power to shock.”

The film’s second half pulls a 180 on viewers and becomes a documentary, wherein players involved are interviewed 50 years later.

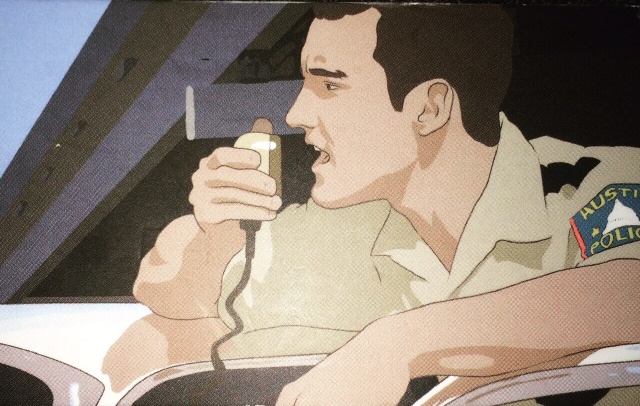

The results are powerful, such as when Austin police officer Ramiro Martinez admits he needed to reflect on the trauma and has let the events stay silent in him for decades.

Then, there’s Claire Wilson, a victim who lay bleeding on the UT mall for more than an hour, losing her unborn baby and her boyfriend in the process. (It took Orlando police nearly three hours to devise a plan to stop Omar Mateen during his own senseless, rage-fueled massacre.)

In an interesting stylistic reveal, Maitland’s film switches from animation to normal film as the real-life subjects begin their testimonies.

Stories hiding between the showers of bullets

Maitland admitted that Claire Wilson’s story became his central motive for making the film, an ambitious endeavor that took four years to complete and encompassed the casting and directing of real actors, the shooting of a documentary, implementing rotoscoping to animate the frames, and fundraising.

In Texas, as in Orlando, the stories hiding between the showers of bullets allow the viewers to hang onto moments of simple and direct humanity. One such moment comes when a woman, Rita Starpattern, breached the Tower shooter’s line of fire to comfort the bleeding Wilson.

When Maitland screened the film at the SXSW film festival, where it won the Grand Jury Prize, he noticed ripples of recognition and surprise from those who had known Starpattern but hadn’t known the story.

“At the time of the shooting, her name was Rita Jones, and she was the wife of the student body president that year,“ Maitland said, “and she went on to lead a very significant life and significant place within the Austin art community. She started a feminist art gallery called Women and Their Work, and she inspired generations of women in Austin.”

Maitland recalled screening the film there for SXSW.

“Something amazing happened,” he said, “because the only time you hear her last name or see her last name is when it’s revealed that she’s passed away. And in that moment, at every screening we did in Austin, you could hear an audible gasp in the crowd from a woman who had known her as Rita Starpattern, artist, gallery owner, feminist. But nobody knew this story. That she had experienced this. Because, like they keep saying in the movie, nobody talked about it. And Rita was one of those people, too.

“She didn’t see this incredible, humane moment in her life as this incredible act of heroism. And she certainly didn’t seek the spotlight or even talk about it.”