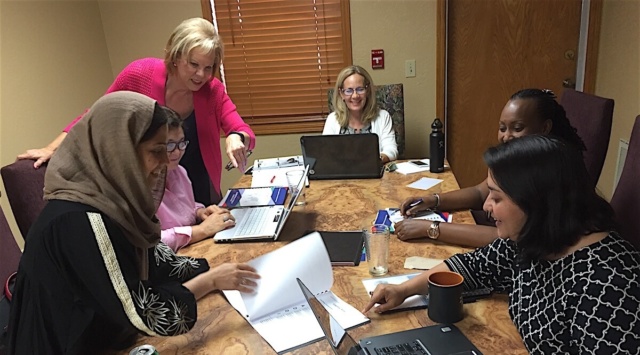

From her brick office building along old Route 66 in northwest Oklahoma City, Terry Neese orchestrates business development and cultural exchange for women in Afghanistan and Rwanda.

“I’ve traveled all over the world. You name it, I’ve been there,” said the veteran businesswoman.

Called Peace Through Business, her program welcomed its 10th class of graduates this month for two weeks of mentorship with top American businesswomen.

“We’ve had some women run for office in Afghanistan,” Neese said of PTB alumni. “President (Paul) Kagame has appointed four of our Peace Through Business graduates to the Parliament and the Senate (in Rwanda). We think that’s huge.”

‘A girl from Cookietown’

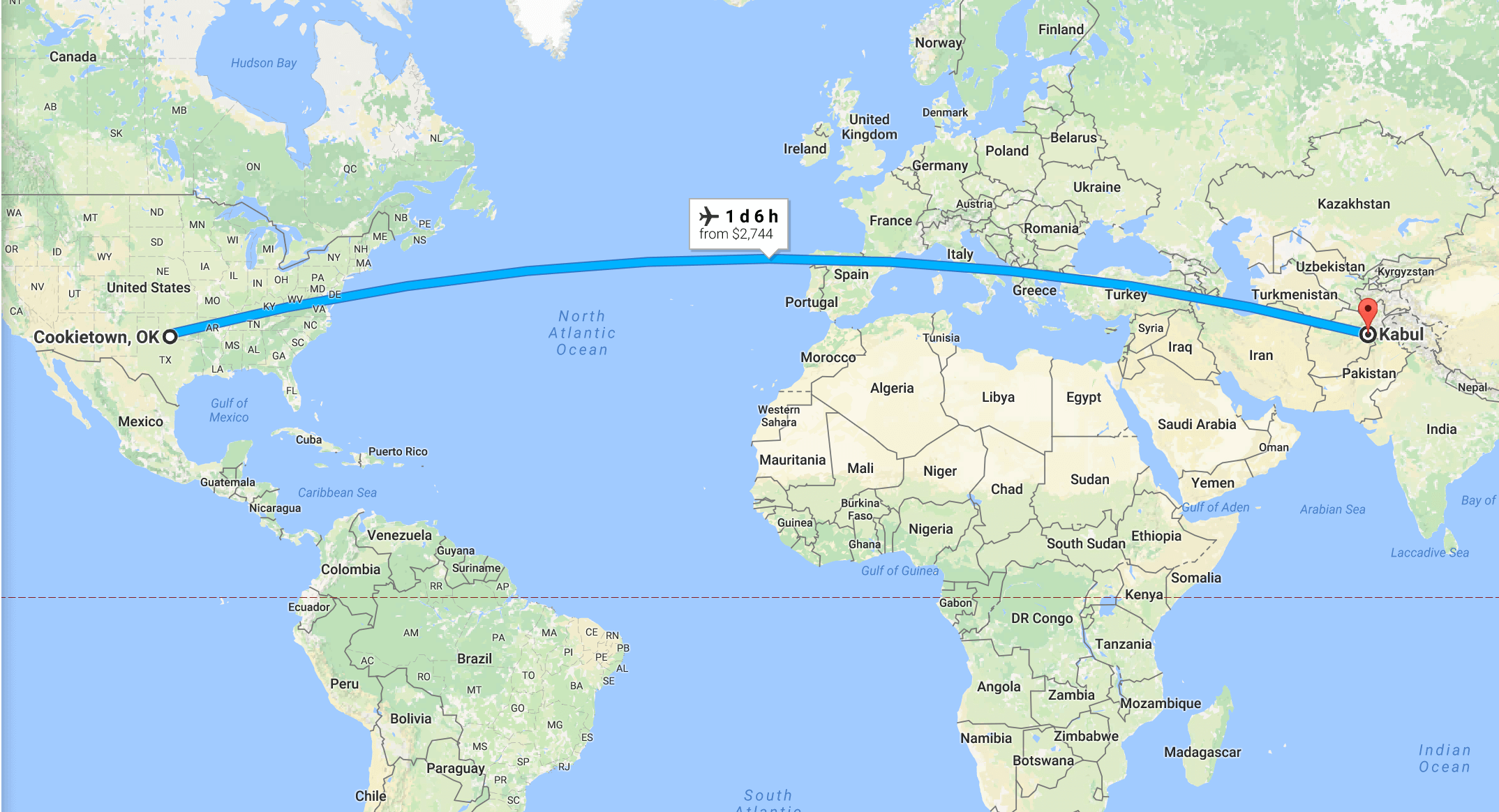

While Neese’s experiences with Peace Through Business have led her around the globe, her roots haven’t strayed far from her childhood home — Cookietown, U.S.A — where her grandfather homesteaded and where she still owns a ranch.

What’s in a name?

Despite growing up there, Terry Neese can’t say which story explaining Cookietown’s etymology is true.

“A cookie truck collided with a car and cookies spread everywhere, so they called it Cookietown?” Neese hypothesized. “Who knows?”

“I was a young girl gathering eggs in the chicken house — cleaning the chicken houses, plowing, harvesting wheat with my dad — and never thought I’d be doing any of this,” Neese said.

This means changing lives and empowering women on three separate continents, with only private funding.

“It was very inspiring for me,” said Muzhgan Wafiq Alokozai, a Peace Through Business participant who has visited the U.S. multiple times now. “I have learned how the American people are really kind, caring and they love sharing their experience, their house and their family — everything — which is not something normal for me.”

“Normal” for Alokozai and her sister, Manizha, includes living in fear of retribution for being businesswomen in Kabul, Afghanistan.

‘A lot of threats and problems’

Much like Neese in OKC, Muzhgan runs a staffing service in Kabul. But her business predominantly serves women, something seen as threatening and inappropriate by many traditional and hard-line Afghan men.

“We have received a lot of threats and problems just by implementing the projects to help women, train women and place them (in jobs),” Muzhgan said. “We have trained about 2,000 women, and we have placed about 70 percent of them in six cities in Afghanistan.”

While Manizha returned to Kabul after her recent visit, Muzhgan and her husband have moved to Virginia, partially for reasons of safety.

“Socially and culturally, it’s not accepted to have more women in public,” Manizha said. “(I could) tell you a lot of really horrible incidents. For example, a girl was killed by some mobs on a Kabul street.”

Manizha is referring to the horrific death of Farkhunda Malikzada, a woman who was kicked, beaten and trampled to death after men accused her of burning a copy of the Quran. She said it had accidentally been placed in the garbage.

“A lot of harassment takes place,” Manizha said somberly. “A lot of it verbal, a lot of touching and such.”

She said communities are often stricter with women in rural Afghanistan, but threats still exist within cities as well.

“In other provinces, we have a lot of incidents of assassinations, killings and attacks on women,” Manizha said. “Recently, for example, we had acid thrown on girls’ faces in Kabul. It was a very expensive area, but it happened there. So they do all these kinds of things to control (women).”

She said women driving, working and running businesses are just a few examples of things that challenge antiquated social norms.

“They get scared that, ‘Oh, now we are losing women!’ That’s the notion in Afghanistan,” Manizha said. “They should not get Westernized. They should not have control over their life and profession. So they do these kinds of acts to spread fear.

“They say, ‘Fathers, tell your daughters, you can not go outside any longer.'”

‘It’s a double standard’

Six days after the sisters’ comments in Oklahoma City, Hillary Rodham Clinton became the first female U.S. presidential candidate nominated by a major political party.

Clinton billed the feat as the “biggest crack” yet in America’s proverbial glass ceiling, something Neese’s own political history can recognize.

In 1990, Neese became Oklahoma’s first female candidate for lieutenant governor. She lost to Democrat Jack Mildren in the general election but ran again in 1994.

That time, she lost by fewer than 8,000 votes in the Republican primary to a state representative from Tecumseh by the name of Mary Fallin.

“When I ran for office in 1990 here in Oklahoma, I would campaign, and I would give my push card out,” Neese recalled. “There were many places across this state where people would recoil — women, too — and say, ‘No, I would never vote for a woman!’

“So, the bottom line is, that wasn’t very long ago.”

Neese pointed to Fallin’s ultimate election as Oklahoma’s first female lieutenant governor and first female governor as progress, but she grimaced when thinking about the names that Clinton, Melania Trump and other American female political figures are often called.

“It’s a double standard,” Neese said. “We have many women elected across the state, but we have a long way to go.”