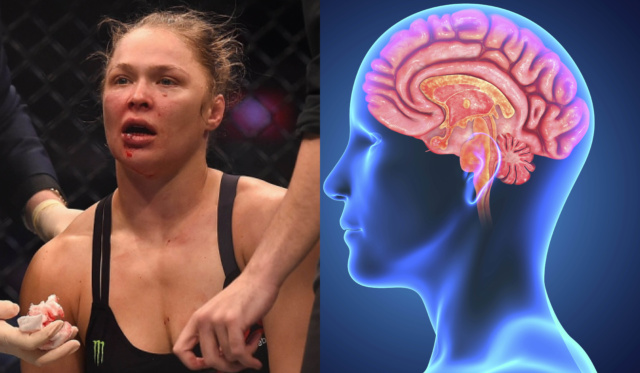

In her 48-second fight against Amanda Nunes last month, Ronda Rousey took an astonishing 23 strikes to the head.

After her second loss in a row, Rousey is considering retirement. After watching that loss, I can’t blame her for considering her health or her future. Rousey, who earned a $3 million purse for her last fight, is in pretty decent financial shape. Her earnings, however, do not represent the typical payout for MMA fighters, and it calls into question how typical fighters afford to take care of their health, among other things, after retirement.

MMA health plan and union

Despite its growing popularity and following, MMA is ill-equipped to take care of its athletes in both the short and long term. The UFC, by far the most profitable and well known promotion, established some form of players’ union only last month. Scouring the internet reveals little about the amount and type of health insurance afforded to MMA fighters.

A 2011 report comes closest by describing a $50,000 per-player-per-year policy for fighters signed to the UFC and Strikeforce. It should be noted that Strikeforce has since become defunct and the UFC was sold to WME-IMG for $4.2 billion in July 2016. Still, working with the 2011 numbers, the UFC’s policy is undoubtedly geared toward accident and catastrophic coverage.

Don’t get me wrong: Catastrophic-coverage health insurance, although appropriate for mixed martial arts, does not address the often chronic nature of injuries resulting from the sport.

The ‘punch drunk’ disease

CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, was first described as a condition of being “punch drunk” or “slug nutty” in 1928.

A result of repetitive head injuries, CTE is associated with the deposition of an abnormal protein called tau in the brain. Although CTE is definitively diagnosed only on postmortem examination by a pathologist by identifying abnormal tau protein, symptoms may be suggestive of the condition. These symptoms include changes in behavior or personality, accelerated cognitive decline or motor impairments, including Parkinsonian symptoms.

Winner by ‘concussive symptoms’

MMA has probably overtaken professional boxing as the form of pugilism of choice in modern society. As such, I hope the recently established fighters’ union of the UFC plans to address the chronic health effects of fighting by demanding some sort of “retirement coverage” for its athletes.

Appropriately addressing chronic injury prevention with regard to combat sports is a tall task. Consider that the most definitive way to win a fight in MMA or boxing is by knock out, or more accurately, by concussive symptoms.

Although CTE originally came to the forefront with regard to former NFL athletes, including Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Jovan Belcher, who shot and killed his girlfriend before killing himself in December 2012, I have little doubt that cases of CTE will rise in the MMA population over time if steps are not taken to make the sport safer.

Until then, it’s important for MMA fans, myself included, to “know where the meat comes from” with regard to combat sports.