In the middle of Oklahoma’s panhandle, various groups have drawn their lines in the dusty, sun-hardened ground of Texas County. Each faction is gambling on its own merits, as a proposal to construct a new casino near Guymon moves forward despite opposition from local citizens and others.

The Shawnee Tribe, which is headquartered more than 400 miles east of Guymon in Miami, Okla., is seeking Bureau of Indian Affairs’ approval as the first step in a process to allow the land to be placed in tribal trust.

If approved, the application would be only the second allowance in Oklahoma for a tribe to build a casino on non-tribal land and the first for a tribe in a county not containing its headquarters. An application by the Kaw Tribe to build a casino at a non-tribal location in Kay County was approved in 2014.

Several lawmakers and citizens in Texas County stand in the way of the Shawnee Tribe’s plans. They oppose the proposed casino for reasons that include the social ills tied to gambling, a loss of tax revenue and concerns about economic effects on the area.

Location, location, location

The proposed Golden Mesa Casino is unique in that it would sit on property not currently considered tribal land. Historically, land must be placed in a trust for a tribe to operate a casino on that land. If the BIA approves the Shawnee Tribe’s proposal, the application would then require approval from the Department of the Interior and then the Office of the Governor before construction could begin.

Brent Gooden, spokesman for the Shawnee Tribe, said the Shawnee Tribe was upfront from the first announcement that the process would be methodical and would take careful planning as the application was being reviewed.

“From the moment we announced the project, we have been very clear the process will take years,” Gooden said. “As expected, the process has been thorough.”

The BIA is tasked with determining if placing the off-reservation land in trust is in the best interest of the tribe and will not be detrimental to the community. Opponents of the casino claim the latter determination is one they believe should be considered a real barrier to the casino being approved.

‘Social costs’ of tribal casino feared, disputed

Lucinda Ray of Panhandle Citizens for Truth in Gaming said many citizens and elected officials oppose the casino owing to concerns about how the community will handle the loss of tax revenue combined with the social problems that can often be linked to casino gambling. She said the concerns aren’t related to the tribe itself.

“It’s not a Native American issue,” Ray said. “The issues are economic. The issues are social costs. The issues are that it is unprecedented.”

Dr. Wiley Harwell, executive director of the Oklahoma Association for Problem and Compulsive Gamblers Inc., said the numbers show Oklahoma has a growing problem resulting from an increase in gambling opportunities. He said 3.2 percent of Oklahomans have some type of gambling problem, which is twice the national average.

“That is a significant number of adults in Oklahoma,” Harwell said.

In a study of the proposed casino, John Kindt said the negatives that come with gambling establishments are well-documented. He presented data that showed local citizens spending 10 percent less on food and 25 percent less on clothing. Kindt also noted that 37 percent of those living in proximity to the casino withdraw their savings to gamble.

In an opposition letter, Guymon resident René Bagley cited the National Bureau of Economic Research to point to a 10 percent increase in auto thefts, larceny, violent crime and bankruptcy in counties four years after a casino has opened. Bankruptcies also increase within 50 miles of a new casino.

“Other studies indicate an increase in the number of suicides, gambling addictions, home foreclosures, domestic violence and social welfare costs,” Bagley said in the letter she sent to the Anadarko office of the BIA. “The individual tribe members will receive all the profits and not have to deal with any of the negative aspects of the casino.”

The National Council on Problem Gambling shows a variety of social issues faced by those labeled as problem gamblers. According to the website, 15 percent attempt suicide, 40 percent commit crimes to acquire money to gamble, 28 percent become separated or divorced, 20 percent have filed or will file bankruptcy, 54 percent have lost their job, and 30 to 50 percent suffer some form of mental illness or substance abuse problems.

Gooden disputed that social negatives were an automatic problem with the construction of a casino in any community. He said the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation had data that showed a lack of consistency in terms of crime increases in areas where casinos were constructed.

“We encourage everyone to research the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Reporting statistics,” Gooden said. “The numbers show no consistent link in crime rates in any Oklahoma town where a casino opened. In fact, in the past 10 years, crime actually decreased in several cities following the opening of casino. The perception that crime rates will increase due to the opening of a casino is simply not supported by the statistics.”

Gooden said casinos train employees to be on an active lookout for anyone who is exhibiting problems with gambling.

“We strive to create a fun and exciting environment where patrons can enjoy themselves,” Gooden said. “As we know, anything done in excess may not be healthy. You have to be responsible. When the game stops being fun, it is no longer a game. We train our employees to not only encourage and support responsible gaming practices, but also to recognize a potential problem and respectfully intervene.”

Economic development? Put it in writing

Proponents of the casino point to economic factors as a significant reason the casino will benefit the area. Michael Shannon, executive director of the Panhandle Regional Economic Development Coalition, said there would a $2.1 million payroll for 46 construction jobs followed by a $3.75 million payroll for 175 casino jobs. These dollars would be paid to employees who would turn around and likely spend the money in the area.

“That type of impact, yes, we are very excited to look at and explore that,” said Shannon, a former city manager for Guymon. “It’s a win-win for the economic future of the Oklahoma Panhandle and everyone involved.”

Shannon said the tourism generated from the casino could have a significant impact on the region. He said when Seaboard Farms came into the region, it led to other new businesses opening in the area. Shannon said he anticipated similar growth occurring as a result of the casino’s construction.

“It’s that spinoff of the big business that is what we focus on,” Shannon said of his group’s support of the casino application.

State Sen. Bryce Marlatt (R-Woodward) said there are plenty of reasons to oppose the expansion of casinos, and he was among those against the Golden Mesa proposal. However, he said some consideration should be given to looking at allowing non-tribal casino operators to come into the state and potentially offer the state a better deal on the revenues.

“There are a lot of social ills that come from gambling, and we see them frequently,” Marlatt said. “If we are going to start branching out of the parameters, maybe we need to reevaluate how we do it.”

Lucinda Ray, from the Panhandle Citizens group, said numbers don’t add up from an economic standpoint. She pointed to a study from Bagley in which she predicts $286,000 in annual sales tax revenue and $195,000 in annual ad valorem taxes would be lost if the casino were approved for the area. Ray said she is concerned the money will go back to Ottawa County rather than being spent in Texas County.

“Nothing is in writing,” Ray said. “Until it is in the compact, it is zero. There is no way any of that is going to trickle back.”

Background

The federal government had not officially recognized the Shawnee Tribe until the year 2000. That year, U.S. Sen. Jim Inhofe sponsored the Shawnee Tribe Status Act of 2000, which was carried by then-Congressman Tom Coburn in the U.S. House. Prior to that measure being passed into law, the Shawnee Tribe was part of and under the political jurisdiction of the Cherokee Nation despite having its own identity, history and culture. In addition to providing official status, the new law allowed the Shawnee Tribe to acquire land in Oklahoma for economic development if the land didn’t already fall under the jurisdiction of another tribe.

In 2004, voters approved Class III gaming in Oklahoma, which cleared the way for what is now legal electronic amusement games, electronic bonanza-style bingo games, electronic instant bingo and non-house-banked card games. Since 2004, Oklahoma has accumulated 127 casinos that generated nearly $4 billion dollars in FY 2014.

The Shawnee Tribe initially tried to construct a casino in 2008 in north Oklahoma City. Opposition from city and state leaders led to rejection of the application, and the tribe began seeking alternative locations.

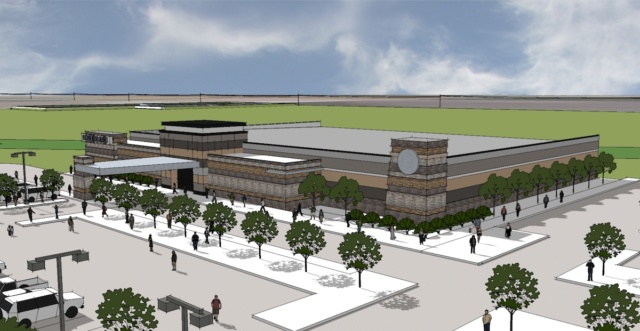

The tribe announced plans to seek the construction of the 42,000-square-foot Golden Mesa Casino on 107 acres in Texas County, two and a-half miles south of Guymon. The Chickasaw commercial company, Global Gaming Solutions, is partnering with the Shawnee Tribe on the entertainment side of the project.

A public hearing was held Jan. 5, on a night when Ray said weather conditions affected the ability of a number of officials affiliated with the process to attend. She said several citizens stood up and spoke in opposition to the proposed casino while one individual spoke in favor of it. Most of the comments focused on issues other than environmental, which was the BIA’s focus for holding the meeting, Ray said.

A letter from Shawnee Tribal Chief Ron Sparkman was read aloud at the meeting, Gooden said.

“Let me assure you, we stand ready to work with the communities and local governments on a shared vision to help build a stronger economy and better place in the Oklahoma Panhandle,” Sparkman had written. “We want to be your community partner and we will work to help citizens of the Panhandle improve their lives through thoughtful investments in the community organizations who share our commitment.”

What’s next

The deadline for opposition to the environmental assessment was Jan. 14, which leaves the decision in the hands of BIA officials for now. Marlatt said his concern is that the Obama administration might attempt to rush a decision on application before President-elect Donald Trump is sworn into office. He said there should be no rush to get this particular application approved until the new administration has had a chance to review it. Marlatt, however, said his position is that the application be denied.

“If it’s not good for Oklahoma City, it shouldn’t be good for anywhere in the state,” Marlatt said.

Harwell, who said he wasn’t opposed to gaming, said it would be tough to predict what the future holds in terms of the casino being approved. He said what once looked to be a certainty was now up in the air.

“A year ago, I would have thought it was going to happen,” Harwell said. “I just think that none of us know at this point.”