(Editor’s note: This story was authored by Jennifer Palmer of Oklahoma Watch and appears here in accordance with the non-profit journalism organization’s republishing terms.)

For decades, principals have come and gone at Tulsa’s McLain High School so frequently, it’s nearly unheard of for a student to complete all four years of high school without seeing a new face in the principal’s office.

The school has had at least 11 principals or co-principals since 2000. Now, it loses yet another one, who, after three years in the job, will leave after the school year.

The frequent change of leadership has sown frustration among parents and community advocates who believe the lack of stability harms student achievement and stigmatizes the school.

North Tulsa residents are pleading with the district to choose a candidate who has a heart for the community and will stay even when the going gets tough.

“We need to have a culture in this school that reflects high achievement, high expectations … We’ve had this (turnover) for ages,” said Darryl Bright, a member of a local advocacy group who attended a forum seeking community input on finding a new principal.

McLain is not the only Oklahoma school struggling to hold on to principals.

The state’s two largest districts, Tulsa Public Schools and Oklahoma City Public Schools, report an average of 15 to 20 principal changes per year. Reasons include transfers, resignations and terminations. Oklahoma Department of Education data show that, last year, 73 percent of Oklahoma’s 1,900 principals had held their positions for five years or less. The rate was 78 percent for high-poverty, high-minority schools.

The poverty gap

In schools considered high-poverty and high-minority, turnover is even higher: More than 75 percent of principals in those schools have been in place fewer than five years, according to the Oklahoma Department of Education.

| Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Principals in place <5 years (high-poverty, high-minority schools) | 69.7% | 69.4% | 76.0% | 78.4% | 77.4% | 78.1% | 77.9% |

| Principals in place <5 years (all other schools) | 63.3% | 61.9% | 64.5% | 66.2% | 67.2% | 69.2% | 70.1% |

Note: High-poverty, high-minority schools are those where the student population is in the 75th percentile of those categories each year.

The constant turnover costs districts thousands of dollars a year. At the school and family levels, the impact can be deeper.

Schools ‘being choked financially’

Every time a school leader leaves, it can be like an earthquake. The aftershocks often include teacher resignations and staff turnover. Programs are abandoned, and momentum is lost. Even if it’s improving, a low-performing, high-minority school such as McLain may stumble backward.

“We often say a teacher is the most important individual factor in the classroom. But we could say the same for a principal, as far as being the most important factor in the school,” said Robyn Miller, deputy superintendent for educator and policy research at the state Department of Education.

Conversations about why teachers leave often focus on low salaries, especially in Oklahoma, which has the third-lowest average compensation in the U.S. – $44,921 including salary and benefits, according to the National Education Association.

Pay isn’t as much of an issue for principals, who earn an average of about $72,000 in Oklahoma, although that’s the fourth-lowest among U.S. states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Instead, a 2014 report by the School Leaders Network found principals leave primarily due to four issues:

- managerial tasks interfering with meaningful instructional leadership;

- personal costs such as long hours;

- isolation on the job;

- and a diminished influence on hiring, firing and funding allocation due to local and state policies.

Chris Howk quit his job as principal of Beggs High School for financial reasons — the district’s, not his own, though he says his pay increased when he took a job as a pharmaceutical sales rep.

He described his former job at the 360-student high school as “basically … telling everybody what they couldn’t do because we didn’t have the money or resources.

“Schools can’t do what’s best for students anymore because they are being choked financially,” Howk said.

Oklahoma City’s Webster Middle School, where more than 85 percent of students are nonwhite and nearly all students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, has experienced frequent principal turnover.

Scot McAdoo, in his first year as principal of the south-side school, said he pushes tasks like emails and planning into the evening hours so he can be a presence in the hallway.

He sings to the students to keep the mood light and has a vision of transforming a neglected outside courtyard into an inviting place to read or hold classes.

“We have students that, on occasion, bring the weight of the world into the school,” McAdoo said. “We’re asking them to learn mathematics, and they’re trying to figure out where they’re going to eat tonight, they’re trying to figure out where they’re going to sleep tonight, and will their family accept them.”

For schools in impoverished areas, the challenges of finding and keeping a good principal are particularly tough.

At McLain in Tulsa, parents and school advocates want a leader who will confront challenges with a sense of mission. All of its 560-plus students are eligible for free or reduced lunch, and more than a quarter are on an individualized education program for special needs.

McLain students are absent an average of 35 days per year, the equivalent of one day a week. The suspension rate is also alarming: More than one in two, or half of the school’s students, were suspended at least once in 2015, according to the state Office of Educational Quality and Accountability.

Most students don’t make it to graduation. The high school reported a dropout rate of more than 55 percent, which is double the district average and well above the state average of 8 percent.

On top of all these issues, Tulsa Public Schools is bracing for more funding cutbacks in the next school year, to the tune of $12 million. The cut would almost certainly affect operations for every school in the system, including McLain.

‘Same soup, warmed up’

School districts often tap good principals to fill administrative positions, or they get shifted to another school to fill a vacancy. But principal turnover leads to teacher turnover, which Willetta Burks, a local advocate for McLain, saw happen during the last leadership transition at the school.

“We wasted four years of children’s education on some type of experiment that nobody ever really bought into, and then we lost a large part of our tenured staff,” she said.

The school’s grade on its state report card has slipped from a D to an F during the tenure of Enna Dancy, who is leaving after this school year to return to her hometown of St. Louis. Dancy declined to be interviewed.

Rodney Clark, a former McLain principal, said the search for new leadership at the high school is “the same soup, warmed up.” The district, he said, is too anxious for a quick fix.

They’ve tried using co-principals and brought in out-of-state visionaries with no ties to the community, as well as other reforms, Clark said.

“People don’t understand the tough decisions that you have to make in regards to making sure your budget is where it needs to be, and keeping quality people there, and making sure everything works in spite of what you have,” he said.

Clark said he lacked autonomy at McLain, but he now leads Langston Hughes Academy for Arts & Technology, a Tulsa charter school serving at-risk 9th and 10th grade students where he has implemented school uniforms, corporal punishment and a focus on social skills.

“You have to change the culture, and to do that, it takes a little time,” Clark said.

A crucial difference

Principals are pivotal to turning around a school, despite being overshadowed often by superintendents and teachers in discussions about academic improvement.

Good principals act as role models for teachers, providing instructional leadership. They influence hiring, firing and teacher retention. And they walk a delicate balance in cultivating relationships with students, teachers, parents and district administrators.

But educators say to improve a school, principals have to stay. Miller, of the state Education Department, said a stable principal is paramount to raising student achievement, retaining teachers and increasing morale.

Principal turnover can have direct negative effects on student performance, the most significant impact right after the turnover.

Turnover at high-poverty schools has gotten worse since 2011. Oklahoma principals working in low-income, high-minority schools stay an average of less than four years, Education Department data shows .

A study by the Wallace Foundation found it takes highly effective principals an average of five years to improve teaching staff and fully implement policies and practices that raise school performance.

“We know it’s not good for a school to have a new principal every single year,” said Stacey Vinson, instructional leadership director for Tulsa Public Schools and once a principal herself. “There’s value in stability and longevity.”

Vinson is working with the McLain community on selecting a new principal. The district has held several forums for community members, students and staff and is forming a transition team to work with the new principal.

Forums are being held at all schools with a principal vacancy in an effort to ensure community members have a say in who leads their schools.

The district will first evaluate principal candidates on the basics, such as evidence of good instructional leadership. Oklahoma requires principals to have a master’s degree and two years of teaching experience.

Feedback from the community will then be used as a kind of “x-factor” to place new hires at school sites that are a good fit, Vinson said. Ideally, new principals will be hired before the end of the school year, which is May 24.

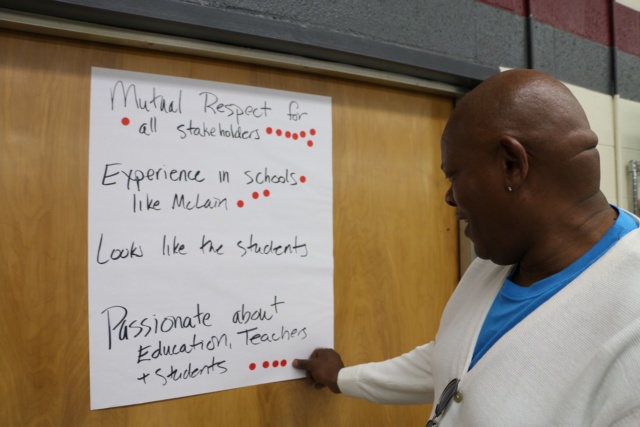

McLain community members have asked the district to find a principal who, among other things, shows a willingness to be held accountable, the ability to build trust, and mutual respect for all stakeholders.

The wants expressed by students so far reflect a need for connection to their school’s leader, Vinson said.

“They want their principal to know who they are. They want their principal to be invested in them and the school,” Vinson said.

(Reporter Brad Gibson contributed to this story.)