I have found my silver lining! The dark cloud of election night and a Donald Trump presidency has lifted — or at least thinned.

Nov. 9, 2016, as I awoke (probably still drunk), picked myself off my bed, dried my eyes and applied my mask, I did what can only be described as a Hail Mary:

I ordered books off Amazon.

While this might seem a small step in a general direction, these were special books. Although I haven’t gotten through them all (yet), the first has given me new pride in my Oklahoma home.

Davis D. Joyce’s collected essays, An Oklahoma I Had Never Seen Before, changes my life with every new sitting. Each essay brings a new facet of our progressive beginnings: from Kate Barnard and prairie populism to a personal essay by Clara Luper, the collection of the people’s history eases the aches in every progressive-stuck-in-a-red-

From teacher to first female legislator

(Editor’s Note: The text below references this article by Jim Logan as well as this book by Musselwhite and Crawford.)

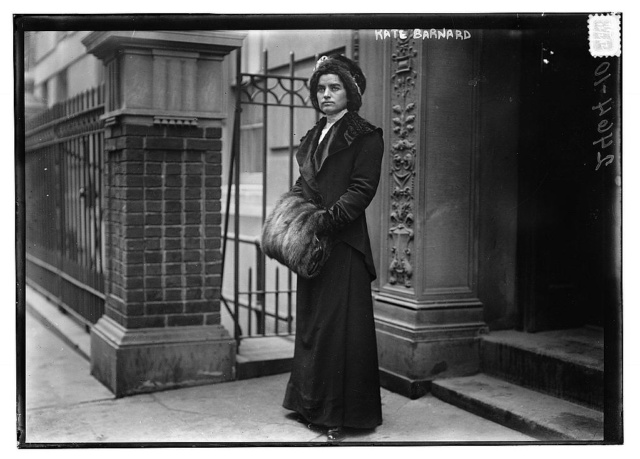

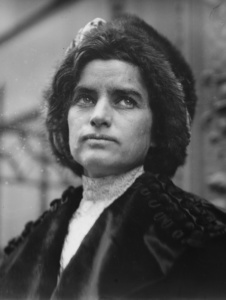

The annals of time have been cruel to our first hero, Kate Barnard. As a pioneering reformer whose political career started almost a decade before the passage of the 19th Amendment, she lives on as a feminist icon for Oklahoma progressives.

Barnard started her career as a teacher in Oklahoma City. Within 10 years, she had moved on to social reform. As one of the authors of the Shawnee Demands, her belief in child-labor laws and mandatory childhood education made a dramatic impact on the Demands, which would soon become the basis for our new state’s constitution.

With the first election, Barnard became the first woman elected to public office in Oklahoma and only the second nationwide (again, before women were allowed to vote). While the first state Legislature expected her to sit quietly in her corner and attend her feminine duties, Barnard had other plans.

Within a year, she had created drastic changes in Oklahoma’s prison system (or lack thereof). Having infiltrated a Kansas penitentiary housing Oklahoman prisoners and seeing the abominable conditions, including torture, Barnard petitioned the state to build its own prison system and end many inhumane practices previously in use. Gaining national attention from the scandal, Barnard began speaking across the country about prison reform.

This, combined with her new crusade championing orphaned Native children, would prove to be her downfall.

Legislature puts kibosh on early activist

Native children were stripped of land and mineral rights, abused by court-appointed guardians and subjected to a racist, capitalist system by ones entrusted with their care. As she continued protecting the rights of children, Barnard would end up taking on judges, representatives and corporations.

In response, the Legislature continuously attacked Barnard as well as her prosecutor. Unable to remove her from office without a popular vote, they gutted her budget and created popular dissidence for her new campaign as well as her focus on speaking publicly nationwide.

Sadly, Barnard faded into obscurity later in life. Suffering from a skin disease as well as other health complications, she died alone in a hotel room at the age of 54. For more than 50 years, her body resided in obscurity in an unmarked grave.

Find solace in Kate Barnard, young women

Today’s young Oklahoman women can take solace in Kate Barnard’s story. In a millennial generation stunted by a poor economy and the shackles of growing student loans, fellow late bloomers remind us that it’s never too late to start caring or effect change. Barnard’s compassion for the poor, unrepresented and abused masses in a state that so often forgets so many of its citizens reminds us all to add a little more sympathy to our everyday humanity.

I highly recommend you visit Barnard’s grave in Fairlawn Cemetery and pay tribute to a local heroine in any way you see fit.