(Editor’s note: This story was authored by Jennifer Palmer of Oklahoma Watch and appears here in accordance with the non-profit journalism organization’s republishing terms.)

Two years ago, Erin DeVoe sent her son, Hayden, to summer camp at a private school at a cost of $250 a week, which crunched her budget.

It wasn’t even full-day, and she had to pick him up mid-afternoon. That can be tough for a working parent, particularly for a single mother like DeVoe, who is a teacher.

“I couldn’t do it again,” she said. “He’d asked about it a couple of times, but I couldn’t do it again.”

When school’s out, many parents face a struggle. Research shows that children without access to a summer and after-school learning activities can suffer academically and slip backward in important subjects like reading and math.

But finding programs that are both enriching and affordable is an arduous task.

For one thing, there is no state funding for out-of-school programs in Oklahoma. And the state ranks low in tapping the main source of federal funds for extended learning — the 21st Century Community Learning Centers.

In fiscal year 2015, Oklahoma schools and nonprofits received $11.9 million in grants for the program, federal data shows. That was $12.41 per child in the state, the 13th lowest rate in the country.

The needs and risks are especially great for low-income families. Their children are more likely to struggle in school, yet parents can’t afford the often steep cost of summer camp and after-school programs. If left at home unsupervised for hours, the students face greater risks of getting into trouble, given the higher rates of crime, gangs and drug abuse in impoverished areas.

Extended learning programs differ from those with a remedial or punitive focus and often include science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM, as well as art and career exploration.

Sheryl Lovelady, executive director of the Oklahoma Afterschool Network, said if the state were to match federal funds, programs could be expanded to many more children.

“Our state should be funding expanded learning,” she said. “Our kids are falling behind. We’re underfunding education at every turn.”

Now the federal program is at risk of being eliminated, alarming advocates and providers alike.

The cost hurdle

As early as January, working parents begin scouring the internet and making calls in search of a summer camp.

Some want a science program, or one focused on arts, depending on their child’s interests. If parents work five days a week, a camp on just Tuesday and Thursday may not suffice.

There are waiting lists and deposits for many camps. Reading negative reviews about a camp on Facebook could cross it off the list.

But the biggest barrier is often cost.

Affordable summer camps are “rare as unicorns,” wrote Lily Eskelsen Garcia, president of the National Education Association, in a February column on parents’ annual ritual of hunting for summer camps.

Nationally, summer programs cost an average of $288 a week per child, and after-school care costs $105 per week, according to the Afterschool Alliance. That’s a burden for even middle-income families, especially those with multiple children.

Low-cost programs do exist, such as through nonprofit organizations like the YMCA or Boys & Girls Club. A handful of free programs also exist, such as through schools receiving federal grants. But they aren’t in every community and struggle to keep up with demand.

According to The Wallace Foundation, which works to improve learning for disadvantaged children, the average cost of a high-quality out-of-school program is $4,320 per student per year. Programs are typically covered through a combination of federal, state and local grants, foundations, private donations, community organizations and families.

Parents, though, pick up most of the tab, even in high-poverty neighborhoods.

This is true even for programs like the YMCA’s, though the nonprofit gives partial scholarships to low-income parents.

More than 2,200 children attended a summer program through the YMCA of Greater Oklahoma City in 2016, and 1,400 participated in their after-school programs. Summer costs $100 to 145 a week, and after-school runs $65 to $95 a week.

Due to increasing demand, summer camp will be offered at 31 locations this summer, up from 26 last year, said Jill Goyette, director of youth development. Still, some locations filled up the first day of enrollment, and that was in February.

Parents shoulder nearly all the costs of the Community After School Program, which provides after-school care and a summer camp for children in the Norman Public Schools district. Director of Child Services Brenda Birdsong said aside from a grant that helps fund a homework club and tutoring, the remainder of costs are picked up by parents, who pay $250 a month per child for a Monday through Friday schedule. Low-income parents can qualify for a discount, but they still pay $200 a month.

Some parents have discovered free or low-cost summer programs through colleges, universities or technology centers. Typically, these are week-long camps with an emphasis on math or science.

Examples are the University of Oklahoma’s architecture and meteorology summer academies and Cameron University’s high school summer science academy. The programs are free to participants and expose students, who are typically high-school age, to STEM subjects. They also are long-term recruitment tool for the schools.

Making the hours work

Balancing program schedules with work hours, especially with multiple children, is also a challenge.

For parents in most school districts, summer break is 10 or 11 weeks long.

Summer camps run anywhere from one week to three months. Some are five days a week, others part of the week. Some last from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m., others from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m.

After-school programs also can vary, though most end at 5:30 p.m. or 6 p.m.

Melody Denton, a nurse, enrolled her 12-year-old son in a STEM-based summer camp at a technology center. But the challenge is getting him there and back.

“It takes a lot of coordination. If something goes wrong, either your patient is waiting or your kid is waiting. I wish there was a kid taxi,” she said, adding that she often gets transportation help from a neighbor and family members.

Some districts are adjusting schedules to ease the burden on parents.

Oklahoma City Public Schools has adjusted its calendar to reduce its summer break to a little over eight weeks.

Santa Fe South, an Oklahoma City charter school, typically has a summer break that is just six weeks long because most of its students are low-income and can’t afford summer camps, said Superintendent Chris Brewster.

This year the break will be longer, at nearly nine weeks, because of construction at the school’s new site inside the Plaza Mayor mall.

Parents, he said, will cobble together activities like church camps, sports camps and visits to grandparents. High school students often work part-time jobs.

“The families we serve are very resourceful and very resilient,” he said.

Tulsa Public Schools has a longer summer break, at 13 weeks. It offers free summer school at selected sites for students attending low-income schools, and promotes to external programs that often cost and last up to a week.

A threatened program

This year, 13,443 Oklahoma children are participating in the decades-old federally-funded program aimed at expanding academic enrichment during non-school hours nationwide.

An additional 230,198 would be enrolled in the 21st Century Community Learning Centers and similar programs if they were available, according to the Oklahoma Partnership for Expanded Learning.

Last year, 55 schools, nonprofits and churches in Oklahoma applied, but there’s only enough money for about 12 new grantees.

President Donald Trump’s proposed budget called for eliminating the federal program.

That worries Robert Hampton, director of Colcord Public Schools’ after-school program, one of 11 Oklahoma school districts awarded a new five-year Community Learning Center grant this school year.

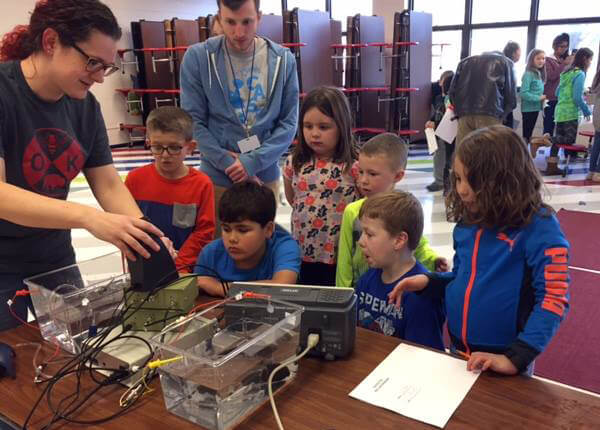

The school district, located near the Arkansas border, used the funds to start an after-school program in which hundreds of students in pre-K through high school now spend hours tinkering with robots, creating art and playing games.

Most of the children come from low-income families. They all receive help with homework, if needed, a snack and a bus ride home, at no cost to their families. For the first time, the school will provide a full-day summer camp this year, also for free.

“We’re a rural community, and there’s not much here in the town for kids to do,” Hampton said.

Demand for such programs far exceeds availability.

In an April 4 letter to congressional leaders, the Afterschool Alliance urged them to maintain the $1.2 billion in funding for the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program. The letter is signed by more than 1,000 organizations.

The program has drawn scrutiny. A Government Accountability Office report this month said it needs more oversight to ensure it is effective.

Students lose ground

Every summer, low-income children lose two to three months of reading, while more affluent students make slight gains, reports the National Summer Learning Association. Most children, regardless of family income level, lose two months of math skills in the summer.

By fifth grade, low-income students are often 2.5 to 3 years behind their peers.

“It’s just good for kids to be in activities through the summer, and so many families just can’t afford it,” said Lovelady, of the Oklahoma Afterschool Network. “It’s a safety issue, it’s an enrichment issue, (and) it’s an academic issue.”

It’s also a workforce issue, she said, because if good, affordable care is available while children are out of school, parents can stay engaged in the workplace.

“We do expect families to work … yet we don’t align our school day with our workday,” Lovelady said. That misalignment, and the cost of programs that fill the gap, exclude many families from participating.

One in five Oklahoma children were unsupervised for an average of 6.6 hours a week in 2014, according to the Oklahoma Partnership for Expanded Learning, which works to raise awareness of the need for such programs. The percentage is higher in rural areas.

With more than 90 school districts now utilizing a four-day school week, there is even more potential for children to be out of school and unsupervised.

“In a traditional community with a five-day school week, there’s already a gap in services,” said Megan Stanek, network director for the partnership. “Now that we have a lot of districts that have gone to four-day, we have an even bigger gap of kids not having anything to do and unsupervised.”