While the 2017 Red River Rivalry offered entertaining football, the handling of Texas quarterback Sam Ehlinger’s frightening head injury should remind fans that collegiate athletic programs often do not have the best interests of players in mind.

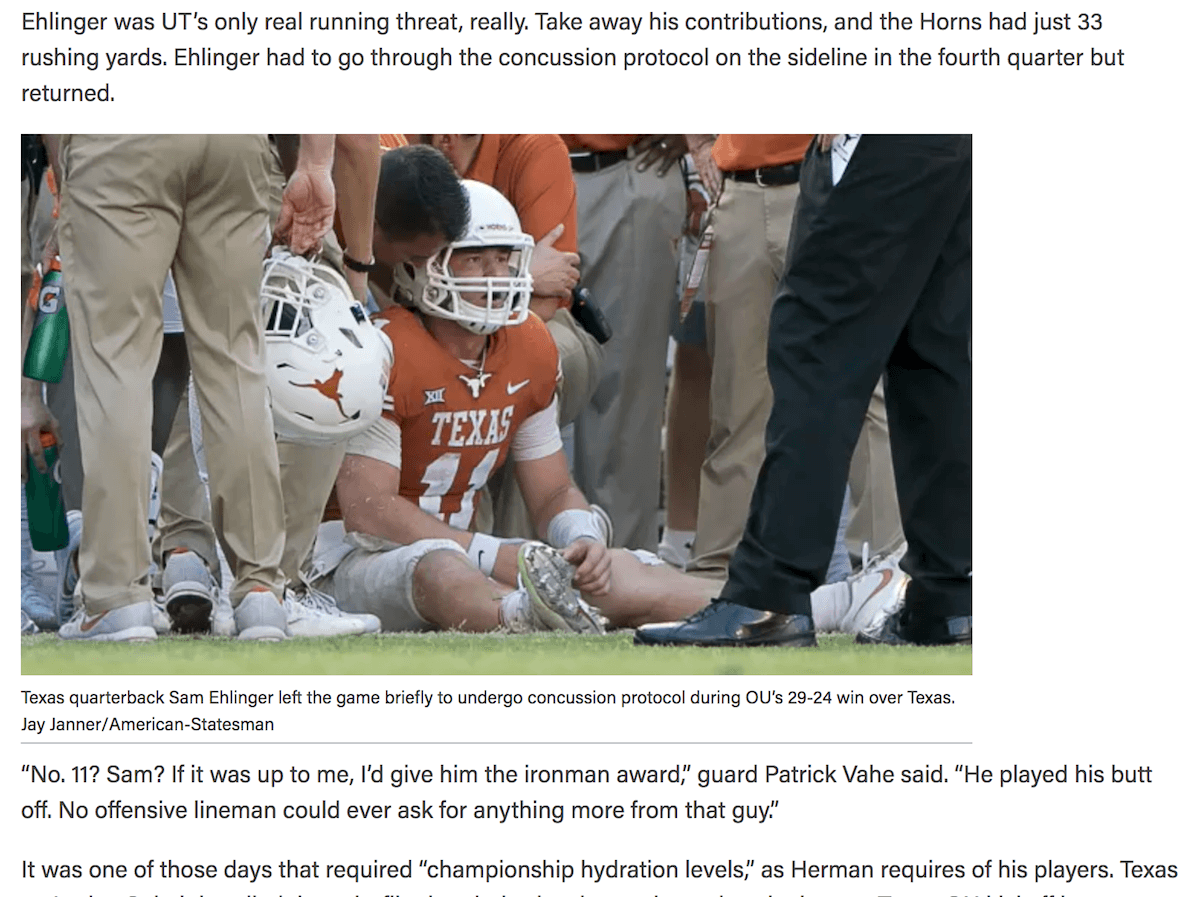

Late in Saturday’s game, Ehlinger scrambled right and was tackled along the sideline, the side of his head whipping violently into the ground. He lay in an awkward position for several seconds and appeared to be posturing, which can result from trauma to the brainstem. While the video above shows Ehlinger’s helmet hit the ground, it does not show his body’s unsettling reaction to the head injury.

Backup quarterback Shane Buechele entered the game for five plays, but Ehlinger reappeared on the field soon thereafter and finished the game.

Afterward and through the rest of the weekend, media coverage of and social media discussions about the 19-year-old quarterback focused lopsidedly on his “feisty, physical” play as opposed to the circumstances of his head injury. Aside from a few tweets, the speed with which Ehlinger returned to the field received little public discussion.

Even the sportswriters who managed to mention the “warrior” quarterback’s possible loss of consciousness mostly did so through the lens of analyzing the team’s offense:

If Tom Herman and Tim Beck ever needed incentive to figure out a way to run the football with the Longhorns’ running backs, it should’ve been watching the film of Ehlinger’s head injury. The kid is a warrior who has “it.” But no one can be expected to survive that kind of punishment the next three years.

While many other media did not, the Associated Press at least described Ehlinger’s head injury and quoted his post-game comments:

After going to the medical tent after he went down hard, Ehlinger returned five plays later. He said he was pulled as a precautionary check for a concussion.

“I wasn’t ever confused where I was at all,” he said. “It was a hard hit. My head hit the ground pretty hard. … I told them immediately I could go back in. I felt fine. They just took me into the tent to make sure everything was OK, go through the protocol and send me back out there.”

Although it is only a still image, this screenshot of an Austin-American Statesman story could tell a different tale:

Why question the handling of Ehlinger’s neurological health when one could write about “championship hydration levels,” of course?

Neuroscientist: ‘We do not have accepted diagnostic criteria’

With 52 percent of respondents to a recent Washington Post poll saying college athletes receive adequate compensation in the form of scholarships, the difference between professional and amateur competitors should be stark: Younger football players are enduring head trauma for far less reward than their professional counterparts.

The protections afforded them are fewer as well.

Unlike the NFL — which established a developing protocol for all teams to follow in 2009 — the NCAA only requires schools to adopt individual concussion policies that are consistent with “best practices” guidelines.

An excerpt from the NCAA’s best practices on “recognition and diagnosis of concussion” raises questions about how the University of Texas handled Ehlinger’s head injury (emphasis added):

All student-athletes who are experiencing signs, symptoms or behaviors consistent with a sport-related concussion, at rest or with exertion, must be removed from practice or competition and referred to an athletic trainer or team physician with experience in concussion management. A student-athlete’s health care provider experienced in the diagnosis and management of concussion should conduct and document serial clinical evaluation inclusive of symptom inventory and evaluation of cognition and balance.

With the AP noting that Ehlinger visited a “medical tent” for evaluation, it seems likely the quarterback was scanned by EYE-SYNC concussion identification technology that the university announced Sept. 1 it would be implementing.

But while that technology scans eye movement “in less than one minute,” it remains unclear how Ehlinger’s examiners dismissed the visual indicators that seemed apparent to millions of people watching on television. The answer could lie in the leniency offered to universities in evaluating concussions.

A key difference between what the NFL and NCAA require of players is that professional footballers must be evaluated in the locker room if there is “suspicion” of a concussion. Amateur student athletes do not receive such overarching protection, instead only being barred from return if a concussion is confirmed on the sidelines.

But such a designation implies a false notion: that someone can be determined not have a “concussion” after quick evaluation.

Even Jam Ghajar, a Stanford University neuroscientist who founded the company that created EYE-SYNC technology, notes in the company’s introductory video that “we do not have accepted diagnostic criteria (for concussions).”

In short, that means neurological trauma — and what sport enthusiasts know as a “concussion” — does not manifest the same among all individuals. Thus, fast attempts to declare someone who has taken a system-shocking brain blow as “not concussed” should be viewed skeptically. In the long term, athletes who sustain head trauma typically undergo neuroimaging that takes far longer than 60 seconds.

As a result, it would seem that any university’s “best practices” for handling a teenager with head trauma should err on the side of caution.

Had the health of Sam Ehlinger been valued more than the outcome of Saturday’s football game, the 19-year-old would have been prohibited from returning to the field.

Follow NonDoc: