(Editor’s note: This story was authored by Paul Monies and Jeff Raymond of Oklahoma Watch and appears here in accordance with the non-profit journalism organization’s republishing terms.)

Seven years ago, with Oklahoma stuck near the bottom in key public health rankings, the Oklahoma State Department of Health and Gov. Mary Fallin set out to reshape the strategy for markedly improving health outcomes for Oklahomans.

The approach would involve new health department initiatives, partnerships, educational efforts and other programs.

There was just one problem: The money to pay for them could run out. And ultimately, that’s what started to happen.

Whether health department leaders and Fallin foresaw those financial risks early on is unclear. But department officials, including the current interim health commissioner and other agency leaders who raised alarms, said this attempt to try new approaches to improving Oklahomans’ health was a factor in the department’s tumble into a cash crisis in late 2017.

“These were initiatives that there was interest in from the governor’s office as well as almost from a national level of how to approach public health,” interim health commissioner Preston Doerflinger told Oklahoma Watch.

The work and funding put strain on the health department in carrying out the programs, he said.

“I don’t know that there’s necessarily a question of whether they were worthy programs or not. It’s just, ‘Were the resources present to be able to pursue them?’”

Investigations are ongoing to find out how the health department’s finances spiraled out of control. By November 2017, the agency needed an emergency injection of $30 million more to prevent severe cuts in staff and programs. Dozens of employees were laid off in early December, and another 161 people will lose their jobs by March. The agency said it will cut next year’s budget by 15 percent — cuts that were detailed in a corrective action report on Jan. 1.

Yet little has been disclosed about programs that drove the agency’s former leaders to use accounting tricks, borrow against restricted federal and state funds and fail to close out the health department’s books. But a review of organizational charts, reports and Board of Health minutes show that discussions about public health morphed into addressing behavioral causes and focused on expanding education and partnerships with other agencies and businesses.

Doerflinger, who took over Oct. 31 after Commissioner Terry Cline and Senior Deputy Commissioner Julie Cox-Kain resigned, pointed to “mission creep” and “agency bloat” as causes of the problems. Doerflinger said former leaders had a hard time saying no to new programs even as state appropriations were cut by almost 30 percent from 2009 to fiscal year 2017.

“When you add new programs or expansion of programs without the necessary resources, that equates to people,” Doerflinger told a House investigative committee on Dec. 11. “There are people brought on for these programs. That’s all good and great, I guess, if you have the resources you need to carry it out and you’re moving the needle (on health outcomes).”

That was echoed by former chief operating officer Deborah Nichols, who testified before the House committee Dec. 19. Nichols said she worked with chief financial officer Mike Romero and others at the agency to explain to Cline and Cox-Kain the severity of its financial problems but were rebuffed.

“When programs would have their funding cut and there were personnel involved, there was a reluctance to let those personnel go,” Nichols said, adding, “They would find ways to move the funding around to keep these folks on board.”

Nichols, who was COO from August 2015 until she resigned in November, said she wasn’t popular among some department directors because she often asked them where the money would come from to pay for their program ideas, including the development of various wellness programs.

“You’re taking money from state funds, you’re taking money from revolving funds, you’re hiring all of these personnel and you’re bankrupting your core financial stability,” Nichols said. “Staff begets staff. You create a program and you say it’s just going to be a little program and then all of a sudden they need 12 people.”

Health officials have not said which grants or other funding sources were improperly managed or diverted, except for an HIV/AIDS grant in which irregularities surfaced and led to closer scrutiny.

‘That ranking is unacceptable’

When Fallin came into office in 2011, she had a plan to supplement the traditional public health model. Priorities such as restaurant inspections, vaccinations and disease testing would remain, but public health leaders were to place more emphasis on centralized delivery and broad education initiatives addressing the behavioral factors underlying dismal health outcomes.

Oklahoma ranked 46th in 2010 in the annual America’s Health Rankings report. In her first State of the State address in February 2011, Fallin cited the study obliquely and signaled that a change in public health delivery was needed, with a greater focus on awareness and personal responsibility. She touted a joint program involving the Health Department and the Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust that awarded grants to develop health-promoting policies.

“That ranking is unacceptable, and comes hand in hand with lost workforce productivity, hundreds of millions of dollars in medical bills, and thousands of preventable deaths,” Fallin said. “Ultimately, the choice to live healthier and be healthier is just that: a choice. But I’m happy to say that the Department of Health has introduced innovative public-private initiatives.”

Fallin and health leaders were taking their cues from the Oklahoma Health Improvement Plan, a 2010 report that set five-year goals for reducing smoking, obesity and heart disease, and improving children’s health. An updated 2015 report noted progress but stressed there was still much to do.

The state now ranks 43rd in the latest America’s Health Rankings report, its best score since reaching 42nd in 2004. Oklahoma was ranked 46th in five of the last eight years.

Cline, who had overseen the state’s mental health agency, took over the health department in 2009 and served as secretary of health under former Democratic Gov. Brad Henry. Fallin appointed Cline as secretary of health and human services in 2011.

“Throughout his career, Dr. Cline has participated and overseen innovative programs that encourage healthier living and address many of the health challenges that confront our state,” Fallin said in a statement announcing his cabinet appointment.

Cline has not responded to requests for comment since his resignation.

Rise of the centers

Loading...

Loading...

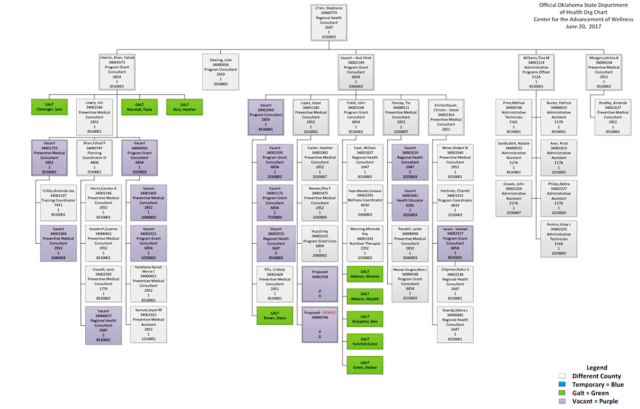

The State Board of Health created the Center for the Advancement of Wellness at an annual retreat in August 2011. The center was to be an umbrella group for anti-obesity, anti-tobacco and other wellness programs. It combined the Strong and Healthy Oklahoma Program and the Tobacco Use Prevention Service. The board also created the Health Planning and Grants unit and shifted Community Development Services away from Community and Family Health Services to the chief operating officer, who at that time was Cox-Kain.

One of the center’s first initiatives was Shape Your Future. Fallin kicked off the campaign a little over a month after her inauguration.

Signs that read “5320” sprung up around the state to spark questions and lead people to think more about public health. (5320 was the number of Oklahomans whose lives could be saved if the state were to meet the national averages on health indicators.) The campaign, a partnership between the health department and TSET, started with a $1 million advertising budget.

Within a few months, more than $2 million had been dedicated to the center reorganization and “related projects,” according to minutes from the January 2012 Board of Health meeting. Some board members expressed approval of the new direction.

By 2014, two more centers appeared on the health department’s organizational chart: the Center for Health Innovation and Effectiveness and Partnerships for Health Improvement. They were also under Cox-Kain, who by now was senior deputy commissioner.

The Center for the Advancement of Wellness lists about 60 positions, including temporary ones and those approved but not filled, a June 2017 organization chart shows.

A prominent grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides an example of growth in the centers in particular and in the agency as a whole. The Preventative Health and Health Services Block Grant grew from nine programs for roughly $713,000 in fiscal year 2012 to 15 programs for almost $1.5 million five years later, grant plans and annual reports obtained under a Freedom of Information Act request show.

The programs included traditional public health work, such as preventing falls among the elderly. But they increasingly included newer approaches, such as addressing tobacco-related health disparities in some minority communities and managing tobacco-prevention messaging on social media. The programs supported 20 jobs, all or in part, by 2017, the reports show.

The agency’s fiscal year 2014 budget featured a Health Improvement category for the first time. Three years later, Health Improvement was 7 percent of the agency’s $403.1 million budget, or $28.2 million. However, because auditors have questioned the agency’s prior budget figures, they may not reflect the actual size and cost of health improvement activities.

Cox-Kain was involved in many facets of public health during the past five years. As well as being Cline’s top deputy at the health department, she led efforts to develop an Oklahoma health workforce plan for Fallin through a National Governor’s Association Policy Academy. Cox-Kain also headed the state’s effort to get a federal innovation waiver to lower insurance costs on the private market.

In a November 2015 presentation to the American Public Health Association, Cox-Kain noted Oklahoma’s repeated low health rankings and gave an update on the Oklahoma Health Improvement Plan.

“We kind of shifted that conversation in our state from the fact that we are poorly ranked … to, ‘What do you have to work on actually to improve health rankings of your state?’” Cox-Kain said. “It is driven by private and public partnerships.” Those included businesses and health-care providers.

Social determinants of health, including educational attainment, jobs and wealth generation, were among the areas that aligned with Fallin’s focus in her second term, Cox-Kain said.

Fallin spokesman Michael McNutt declined to make health policy experts in the governor’s office available for comment and referred questions to the state health department.

What’s next

In response to the health department scandal, Fallin formed the Joint Commission on Public Health, which held its first meeting Jan. 5. The commission will study alternate methods of delivering public health. The nine-member commission is being led by Gary Cox, executive director of the Oklahoma City-County Health Department.

The health department runs 68 county offices, with some smaller counties getting services from larger adjacent counties. Oklahoma and Tulsa counties have consolidated city-county health departments that enjoy a degree of autonomy from the state agency.

“We do have a system in Oklahoma that has a considerable amount of central control through the central office,” Cox said. “Is there a better way of doing it so the county health departments have more control as far as how funds are spent, who you partner with and the ability to write grants with organizations in your community?”

Doerflinger said the health department remains in financial crisis but he hoped the commission will provide recommendations to change the way the agency does business. A report is due March 1.

In a remark that echoed hopes from seven years ago, he added, “This is one of those watershed moments for the state of Oklahoma to change the way we approach public health in the state.”