(Editor’s note: This article about Benjamin Petty’s conviction cites court documents concerning the graphic sexual abuse of a minor, which some readers may find disturbing.)

How does a 36-year-old man avoid jail time after admitting to the rape of a 13-year-old girl at an Oklahoma church camp?

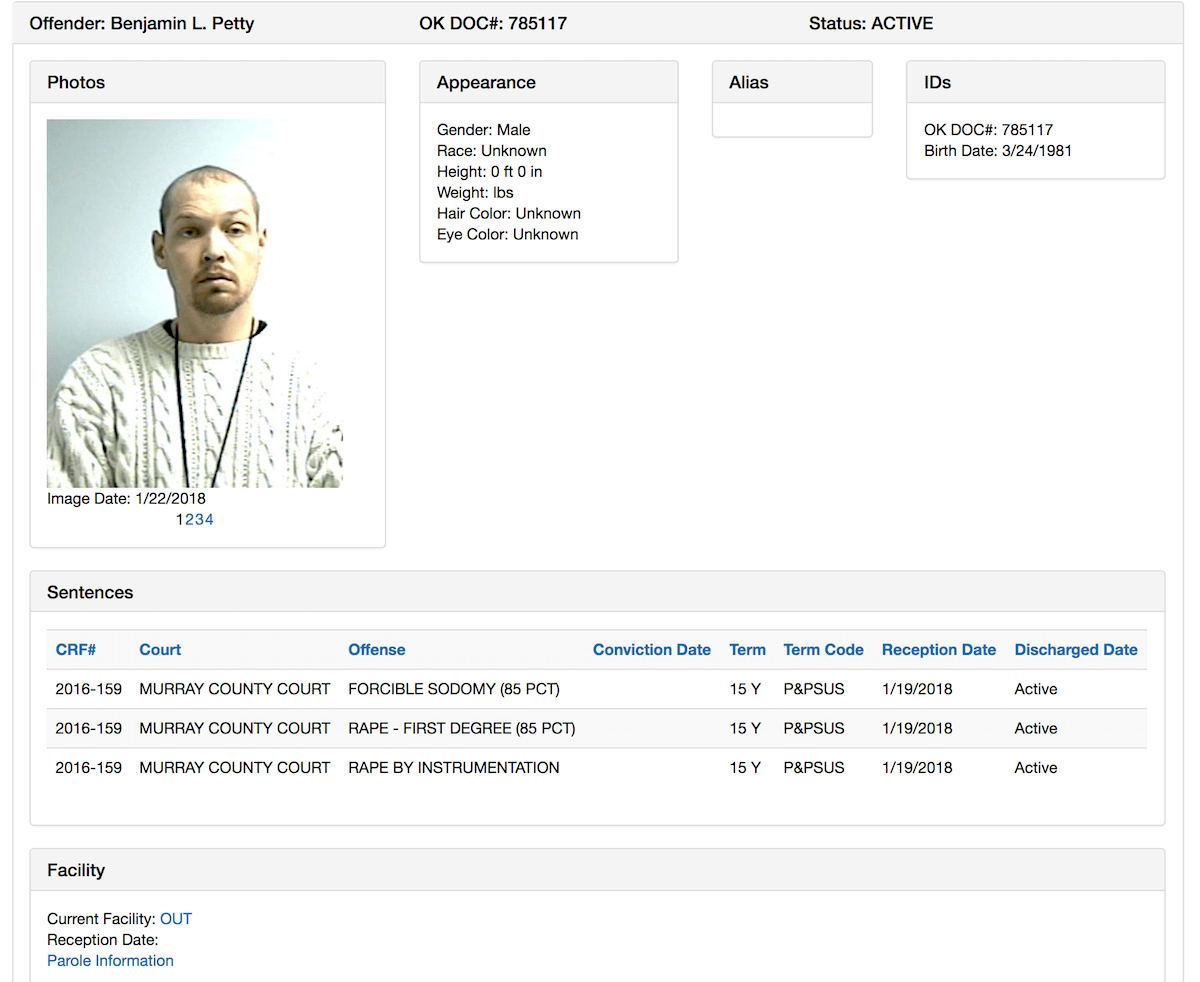

That’s the question many have wondered this week after Benjamin Lawrence Petty pleaded guilty to attacking a Texas girl attending the Falls Creek Baptist church camp near Davis in June 2016.

But hidden beneath those headlines is the story of a court system struggling to find justice without causing more harm than good.

When Murray County Assistant District Attorney David Pyle made a plea agreement with Petty’s defense lawyer that involved a suspended sentence — but no prison time — for first degree rape, forcible sodomy and rape by instrumentation, it unleashed a hornet’s nest of criticism from outraged victim’s rights advocates and shocked citizens.

Understandably so. A general thought is that sex offenders will re-offend. Allowing them to walk the streets creates a risk to the public that would seemingly be avoided by incarceration.

But what happens when protecting society conflicts with protecting a victim?

“My feeling about the plea agreement is that the plea agreement was done in an effort to protect [the victim],” Pyle said in an interview with NonDoc hours before he resigned Wednesday.

Pyle’s boss, Carter County District Attorney Craig Ladd, said in a prepared statement that the case was handled by Pyle in a way that did not reflect Ladd’s “thoughts or position on how rapists, especially those who prey on children, should be dealt with in the criminal justice system.”

But, had Pyle not come to a plea agreement with Petty’s attorney, a jury trial would have necessarily required the young victim to take the witness stand and testify how Petty tied a rope around her wrists, raped her and then threatened harm if she told anyone, according to the criminal charge.

There is no doubt that one rationale for the plea agreement by the assistant district attorney was the potential psychological harm such testimony might have on the victim, who would be compelled to re-live the rape — this time in a courtroom full of lawyers, 12 jurors, her family and others.

Examining Jane Doe’s civil lawsuit

I have been a lawyer in Oklahoma for 31 years. During that time, I have represented children who were victims of an adult rapist. And yes, as distasteful as it may seem to non-lawyers, I have also represented more than one child molester. Like it or not, it is the role that lawyers serve to our society. Of those cases, my experience was not in criminal proceedings, but rather in civil lawsuits brought by the victims seeking monetary damages from the offenders.

So in reading past the headlines this week, I wondered whether the Petty case’s plea agreement might have an impact on its parallel case — a civil lawsuit seeking financial restitution for the Falls Creek rape victim from the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma, a Midwest City church and the girl’s home church in Terrell, Texas.

From the filings in that civil case, we can learn a great deal more about the situation at hand.

On June 13, 2016, Benjamin Petty was brought to the Falls Creek church camp by the Country Estates Baptist Church of Midwest City. He was one of the volunteer adult sponsors of their youth group, and he went along to help out as a cook during the camp.

The Midwest City church’s group was paired with a similar youth group from The First Baptist Church of Terrell, Texas, which included the 13-year-old girl who would be raped by Petty three days later.

The two groups shared the same large cabin on the Falls Creek property, which is operated by the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma, an organization of Baptist congregations in the state.

The 13-year-old girl is referred to in the civil case with the assigned name, “Jane Doe,” to protect her real identity. The lawyers in the case have come to refer to her merely as “Jane”.

The lawsuit, filed in Oklahoma County District Court, alleges Petty utilized sexual predator tactics of pursuing and gaining psychological control of Jane.

It claims he lured her to a backroom of the cabin, promised to teach her how to use and perform tricks on a toy he had brought to gain attention of youth campers, then tied her hands behind her back and violently raped and sodomized her.

The lawsuit alleges the church groups failed to perform a background check on Petty.

However, a background check would have only revealed a misdemeanor DUI. He had no recorded history of sexual violence and no felonies of any kind.

But the lawsuit also alleges the church groups failed to take any preventative action to stop Petty’s “open and obvious” conduct in targeting the girl.

A major battle is underway in the civil case that also raises the risk of compelling the victim to re-live the rape.

‘It is outrageous to ask this of a child’

Bruce Robertson, a noted Oklahoma City lawyer, represents the victim in the civil lawsuit filed in Oklahoma County District Court.

It is customary for such lawsuits to be brought in the name of the parents on behalf of their child. But, in this case, Robertson arranged for Oklahoma City minister Lori Walke to serve as the girl’s court-appointed guardian ad litem, who could then bring the lawsuit in the guardian’s name, rather than revealing the name of the parents.

This month, Robertson asked Oklahoma County District Judge Alicia Timmons to prohibit lawyers for the church defendants from obtaining discovery about the girl’s sexual history.

Lawyers for Country Estates Baptist Church of Midwest City had submitted written interrogatories to Robertson’s client, asking her to reveal her voluntary and involuntary sexual history for the previous six years. The interrogatory pointedly asked about any vaginal or anal penetration, fellatio, and cunnilingus, and to reveal the dates of such activity and identity of participants.

Understandably, Robertson objected and refused any answer. Instead, he said in pleadings to the court: “It is arguable that an inquiry into the past six-year sexual history of an adult would be temporally excessive, but it is outrageous to ask this of a child.”

Court pleadings filed by the defendants state that the then-13-year-old revealed to church counselors in Texas that she and her sisters had been sexually abused by a step-uncle numerous times for several years. The defendants asked Timmons to allow a deposition of Texas child welfare officials to learn details of investigations into the alleged abuse, contending it is relevant to her claim of damages for emotional distress she is attributing solely to the Falls Creek rape.

RELATED

Educating on consent, sexual assault ‘falls on all of us’ by Jessica Fisher

The lawyers also wanted to inquire of the girl’s alleged prior consensual sexual activity. Their argument was that previous harm from sexual activity may account for some of the emotional distress being claimed in the lawsuit, rather than the rape at Falls Creek.

Harlan Pinkerton, a lawyer for the Midwest City church, said at a court hearing on Jan. 4 that “Jane” had bragged about having sex prior to the rape.

“It is completely relevant to damages, because once she’s told, she’s talked about it, she’s bragged about it, she’s disclosed it,” Pinkerton said.

Timmons rejected the church lawyer’s argument.

“I beg to differ with you. I don’t think it has any — even a scintilla of any relevance to anything. I just don’t,” Timmons said from the bench.

The Oklahoma Rape Shield Law

Judge Timmons did allow the lawyers to obtain Texas child welfare investigative records about the Falls Creek incident, but not any other investigations, including an inquiry into the alleged abuse of Jane’s siblings.

FOLLOW NONDOC

Gregory Ziegler, a Dallas lawyer representing the Terrell church, contends that not only is Jane’s prior sexual history relevant, but that it is necessary for his expert witness to perform a psychological evaluation of her. It is common for defendants in a civil lawsuit to hire expert witnesses with scientific or medical credentials to review cases and offer opinions on various issues, including the damages being alleged.

Ziegler hired Dr. Barbara Ziv, a Pennsylvania forensic psychiatrist who has appeared on Oprah and other television shows, to do a psychiatric evaluation of Jane.

Ziv provided an affidavit stating the girl’s sexual history and any evidence of other abuse would be necessary to do an evaluation. She also said a face-to-face interview of the girl and a deposition by the church lawyer asking questions about her other sexual activity and abuse would be necessary, too.

“It is imperative that my interview of Plaintiff include her past psychiatry history, past sexual history and her history of trauma and abuse. Without that interview, I cannot properly and thoroughly perform an independent psychiatric evaluation,” Ziv stated in the affidavit.

Ziv’s evaluation might include an assessment of the victim’s family environment. That would give the church’s lawyers an argument to pry into sexual abuse of the girl’s sisters, which they contend was revealed to counselors and investigated by Texas authorities.

A psychiatric examination or deposition of Jane has not yet happened. But if the civil case does not settle, it is possible such an examination or deposition could occur — if the court determines such discovery is permitted by the law.

Jane’s lawyer, Robertson, contends the Oklahoma Rape Shield Law should prevent any such inquiry.

That Shield Law prohibits the admission at trial of evidence of a victim’s other sexual behavior and evidence offered on the issue of whether a victim consented to the sexual behavior involved in the crime.

But the statute does not apply to civil lawsuits in Oklahoma.

And the rules for discovery in civil lawsuits tend to be liberally construed. The idea is that, to avoid ambush at trial, the parties in a civil lawsuit have wide latitude as to what they can find out in discovery through depositions, written interrogatories and document production requests.

That doesn’t mean it gets admitted by the court when the trial rolls around, however.

And, as Timmons decided, sometimes even discovery can go too far if it can cause embarrassment and harassment. In those circumstances, the court rules allow for an order that prohibits it.

‘I’m sorry that I can’t discuss the factors in this case’

Benjamin Petty’s sentence includes 15 years of probation, two years in an ankle monitor and lifetime registration as a sex offender. Had his case gone to trial, he could have received jail time, but he also could have been acquitted.

The Oklahoma Rape Shield Law may have applied in a criminal trial of Benjamin Petty, thus preventing testimony about Jane’s past sexual history. But there are exceptions to that rule. The judge might have allowed defense lawyers to cross examine Jane about “bragging” or making prior false accusations. After all, the defense would have tested Pyle and the state to meet its substantial burden of proving that a rape occurred.

If the victim had told different stories at Falls Creek, she might have been facing a very rigorous cross examination by a lawyer defending the criminally accused.

Defense lawyers have a job to do: defend their clients. They took an oath to do that, and when the consequences are possible prison time, the defense can get ugly with witnesses.

We don’t know for sure, but that might have been what Pyle, the assistant district attorney, was concerned about if a plea agreement was not struck — not only what impact it might have on the victim, but also what impact it might have on getting a conviction.

Cases settle to avoid risk.

“I want the public to understand that I take these cases very seriously,” Pyle told NonDoc. “There are some facts of the case — in all cases — that cause you to recommend and accept some type of plea agreement, whether it is more than you think is fair or less than you think is fair.”

Pyle, who was a defense attorney for two decades before serving as a prosecutor over the past four years, emphasized that he could not discuss many facts of Petty’s criminal case.

“I raised four daughters. I’ve got four grandkids, and three of them are girls. So I take this very seriously when it comes to making these kinds of deals like this,” he said. “I don’t know what it’s like to have a child in that position, but because of my background of raising my children, it is near and dear to my heart. And I’m sorry that I can’t discuss the factors in this case that have caused this plea agreement to be made, but I simply don’t think I can.”

A poor showing by Jane under the pressure of the criminal trial could also have seriously crippled her civil case — the one her lawyer hopes will eventually result in a monetary settlement to pay for future counseling.

An acquittal of Petty would have torpedoed the civil case and emboldened the church defendants to reject any settlement before trial — thus subjecting the victim to more trial testimony on the civil side.

Jane’s lawyer was present at Petty’s sentencing. Pyle said her lawyer advised that his client’s family was OK with the plea agreement — a statement the girl’s lawyer later said was true, but only owing to the DA’s representation that Petty would likely avoid substantial time in prison because of his diabetic condition.

Regardless, getting a conviction of Benjamin Petty by virtue of the plea deal did help Jane’s civil case. Now, the plaintiff will not have to prove a rape occurred. That issue was determined by the Murray County judge when he accepted Petty’s guilty plea. It established liability of Petty, which the plaintiff hopes to have the judge in Oklahoma County legally attach to the Midwest City church and also reflect negatively on the Texas church and the Baptist General Convention.

And, Petty’s pleading avoided a possible witness collapse of the victim that could have been used against her in the civil litigation.

A child’s best interest vs. a desire for retribution

I have seen firsthand how our court system can fall short in protecting the child victims of sexual abuse.

It was more than two decades ago that I represented a pair of 7-year-old boys in their civil claim against a babysitter who molested them.

The perpetrator was criminally prosecuted by the district attorney. The boys were required to testify at the preliminary hearing. They took the witness stand. They were asked all those questions. They were asked to re-live the event.

But they could not find the words to tell their story. The charges were dismissed.

And so, when I read the headlines this week about the plea deal that let a rapist avoid prison, I knew there was more to this story.

I agree that adults who sexually abuse children should go to prison. It is punishment that is deserved. I also know that retribution makes the rest of us feel better about ourselves — as if we are doing something about the problem.

Lost in the headlines, however, is how these events affect real people. Real children. And each case has its own circumstances and choices to be made by those involved.

Sometimes doing what is in one child’s best interest may not be what the public wants to soothe its conscience.

Meanwhile, in today’s world, being tough on crime is the political mantra that can get one elected. Looking like you are not can get you fired.

(Editor’s note: William W. Savage III interviewed David Pyle for this article.)