(Editor’s note: This story about opportunity zones was authored by Paul Monies of Oklahoma Watch and appears here in accordance with the non-profit journalism organization’s republishing terms.)

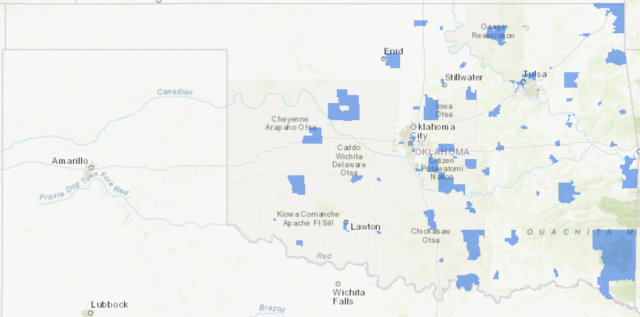

A new federal tax incentive to encourage long-term investments in low-income areas includes most of downtown Oklahoma City and Tulsa and other pockets of prosperity in the state, but excludes many areas that are impoverished.

The contrasts raise questions about how the areas, called “opportunity zones,” were selected and whether the tax breaks will attract investments that mostly benefit extremely poor areas or ones where investments were already going.

A review of the above map showing Oklahoma’s zones brings home the point.

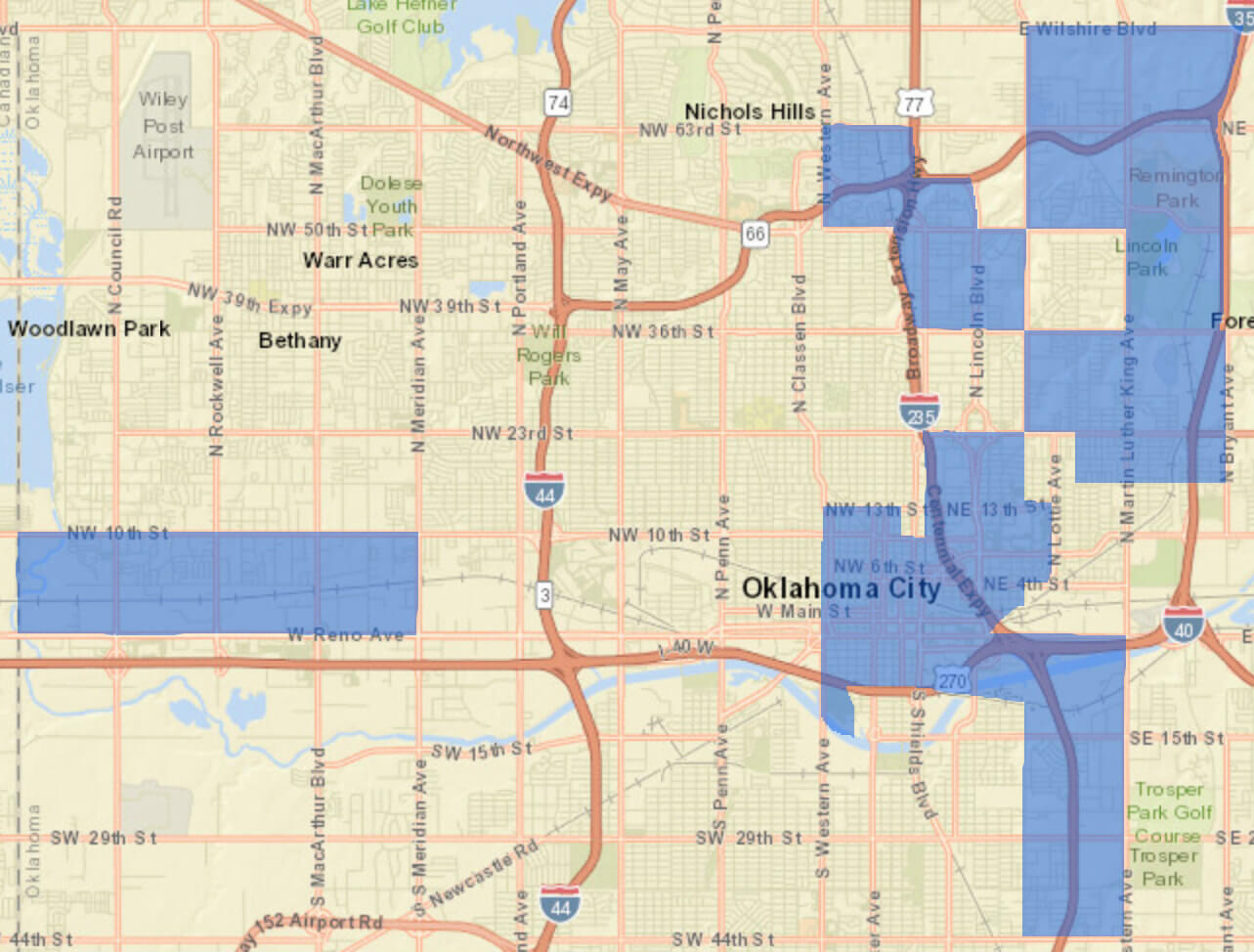

Oklahoma City opportunity zones cover much of Midtown and most of downtown. They take in the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center complex but miss some of the low-income, predominantly black neighborhoods adjacent to it. The northeast-side zones include the Northeast 23rd Street corridor, which the city has long targeted for increased investment, Martin Luther King Avenue and the I-35 corridor. A zone does include a troubled industrial and low-income stretch on the west side between I-35 and 10th Street.

Another zone abuts high-income Nichols Hills and includes the Chesapeake Energy campus, although it also extends into industrial and residential areas off Lincoln Boulevard. Little of the south side of Oklahoma City is included, except the former Crossroads Mall area. (Santa Fe South charter school occupies the former mall.) The Capitol Hill area is not included.

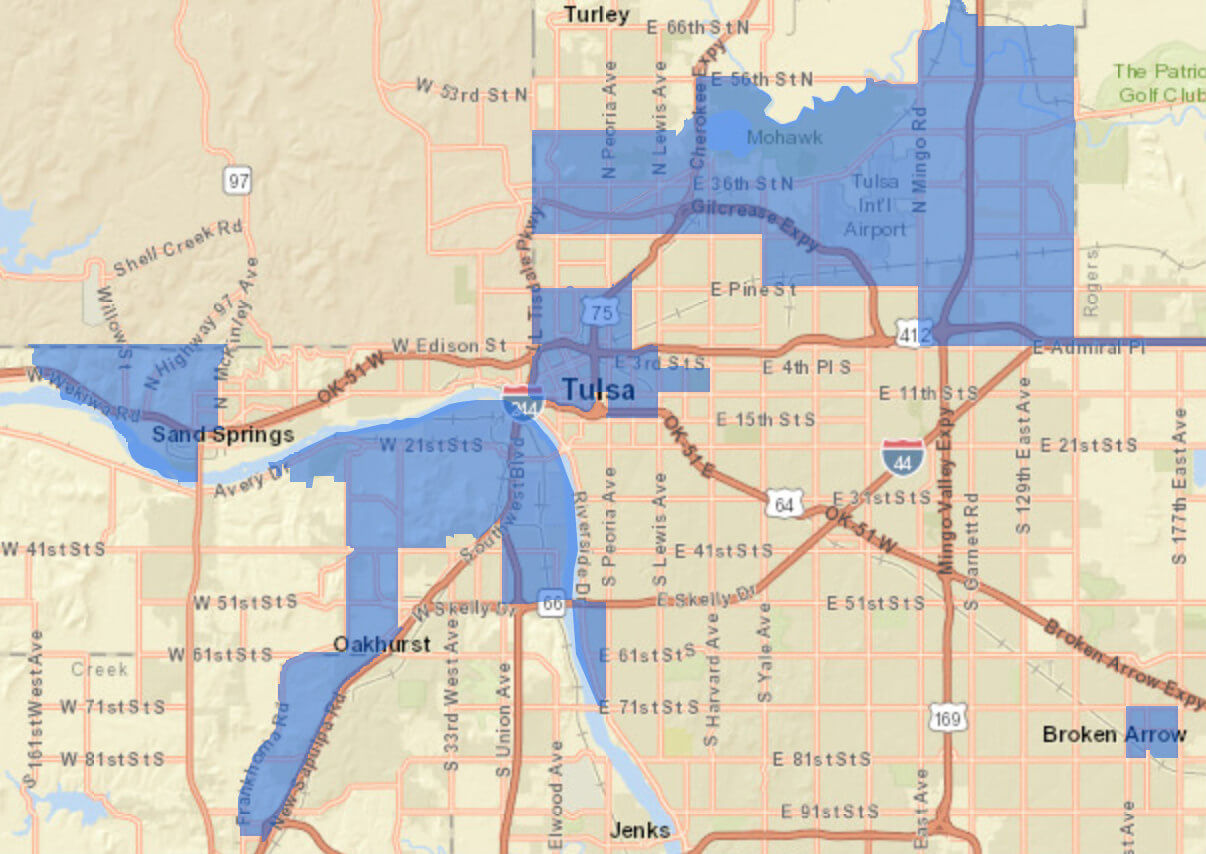

In Tulsa, chunks of the historically black north side were left out, although the downtown zone and Tulsa International Airport areas include some surrounding neighborhoods. Tulsa’s other zones include the industrial west side of the Arkansas River, Sand Springs, the University of Tulsa area and a single tract around Broken Arrow’s entertainment and shopping “Rose District.”

Google’s data center, which is being expanded again, is in an opportunity zone in the MidAmerica Industrial Park south of Pryor. It’s the only zone in Mayes County, which has five other low-income census tracts that didn’t make the state’s cut. Most of McCurtain County, in far southeastern Oklahoma, is an opportunity zone. That area has long struggled with poverty, but also encompasses holdings of timber giant Weyerhaeuser.

Thirty Oklahoma counties do not have any opportunity zones. Oklahoma and Tulsa counties each have 21.

Opportunity zones created during 2017 tax overhaul

Opportunity zones, which were part of a package of tax cuts Congress passed in late 2017, allow investors to reduce or eliminate federal capital gains taxes.

The investors can be individuals, companies or funds set up specifically to invest in the zones. There are no caps on the incentive, although investment must go into low-income census tracts selected by governors in each state. The law allowed states to designate up to one-fourth of their low-income census tracts as opportunity zones. For Oklahoma, that means 117 of the state’s 465 eligible low-income tracts. Nationwide, 8,764 zones were designated as opportunity zones.

State and city leaders are touting the opportunity zones in meetings and online. Investment seminars are being organized on the coasts to attract high-net-worth individuals. Officials say the program is a prime opportunity to accelerate investment that benefits both specific areas and broader surrounding ones. One analysis shows $6.1 trillion in unrealized capital gains are on the books of corporations and individuals.

“Even a small fraction of these gains reinvested into opportunity zones would constitute the largest economic development initiative in the country,” John Lettieri, co-founder of the Economic Innovation Group, told Congress in a hearing last year.

Others are skeptical. They question whether the program will live up to its purpose, saying the investments could increase gentrification in urban areas and displace poorer residents. They also worry much of the money will go INTO big-ticket urban real estate deals that already made financial sense.

“The fundamental problem with opportunity zones is the disconnect between the size of the potential tax costs, which are uncapped, and the social benefits from the investments, which will be hard to measure,” said Steven M. Rosenthal, a senior fellow in the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center at the Urban Institute.

Downtown Oklahoma City has seen hundreds of millions in public and private investment in the past several decades. In the seven tracts that make up much of downtown, the Census Bureau estimates their total population at just 3,800 people, although hundreds of new apartments have been built in the past several years. The tract covering Chesapeake has roughly 2,300 residents.

To designate the low-income tracts, the federal tax law said states must use five-year population estimates from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey for 2011-2015.

The only businesses that don’t qualify to participate are gambling establishments, country clubs, golf courses, massage parlors and liquor/beer stores. Theoretically, an energy company could invest in oil and gas or renewable energy projects located in an opportunity zone. Investors or companies also could target specific industries, like aerospace, or community needs like affordable housing.

Oklahoma zones chosen without public meetings

The zones were announced with little fanfare and no insight into the criteria used to select them. The tax law gave states’ governors complete autonomy, as long as they met certain income or poverty requirements. Oklahoma had 90 days to select the opportunity zone tracts last year. Through the Oklahoma Department of Commerce, Fallin’s office consulted with chambers of commerce, tribal leaders and economic development officials to make the designations, said Leslie Blair, a spokeswoman for the Commerce Department.

At least 34 states had some type of public input on the designations of opportunity zones, according to the Economic Innovation Group, which helped develop the policy and is monitoring its implementation. Both California and Colorado published draft maps of zones, which were then refined with public input. Oklahoma did not hold any public meetings because they weren’t required, Blair said.

In addition, governors were allowed to designate a small number of tracts next to low-income tracts. But those tracts must have median family incomes that don’t exceed 125 percent of the median in the adjacent low-income tracts. No more than 5 percent of a state’s opportunity zones can have that contiguous designation.

Gov. Kevin Stitt, Oklahoma City Mayor David Holt and Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum have all touted the potential of opportunity zones to attract new investment to the state.

“It’s going to be a tremendous opportunity for Oklahoma to recruit businesses to our state,” Stitt said at a Jan. 17 press conference. He designated Lt. Gov. Matt Pinnell as his administration’s point man on development of the zones. Pinnell plans a series of summits in the coming months to promote the zones in rural areas.

Holt, who took office in April, said the zones were designated before he took office and the state led much of the process. Overall, he’s happy with the 21 zones in Oklahoma City, although he wishes the Capitol Hill area in southwest Oklahoma City had been included.

“The opportunity zones downtown and in the Innovation District (east of downtown) are obviously low-hanging fruit and probably sell themselves to some extent, but we would really feel disappointed in the end if we weren’t able to leverage them to get more investment in Northeast 23rd or Crossroads Mall or Northwest 10th, some of those more challenged areas that are also a part of the opportunity zones,” Holt said

‘They’re still very much distressed areas’

With the zones designated, state and city officials are in marketing mode. Oklahoma City is partnering with a nonprofit, Accelerator for America, to come up with a prospectus for investors. The city’s opportunity-zone effort is coordinated by the Alliance for Economic Development, which contracts with the city for economic development.

“We took a look at all of the eligible tracts and then from there tried to figure out the areas of this city where there was a planned public investment for now or in the near future that could potentially spur additional private investment,” said Kian Kamas, Tulsa’s chief of economic development.

For example, Tulsa picked census tracts along a new bus rapid transit route that extends to North Tulsa with a plan to attract a major employer to the area. The View is one of the city’s first housing developments to take advantage of the incentive and has designated 20 percent of its units for affordable housing, Kamas said.

“They’re still very much distressed areas where there’s a lot of work to do, but we knew that we already had strategies in place that would allow the city to make public investments or where we knew there were already planned philanthropic investments that could really help encourage and maybe reduce the risk or perceived risk of a private investor,” Kamas said.

The Commerce Department is contacting city and counties with opportunity zones to see what kind of investments could be marketed to investors, said Jon Chiappe, director of research and economic analysis. It also plans to reach out to qualified opportunity funds, which allow investors to pool their money in funds that invest in the zones.

“If we can highlight some of these opportunities to investors outside the state, then we can potentially attract capital to this state for development,” Chiappe said. “In Duncan, it might be an industrial park. In Bartlesville, it might be affordable housing and whatever’s important to that community.”

The agency is also trying to track investments to see if the opportunity zone designation had a positive effect on poverty and employment. The incentive is more beneficial the longer an investor has money in a project or fund, so gathering that data will take time. In a joint letter to the IRS, Oklahoma and 11 other states urged federal officials to require opportunity funds to report where they’ve invested in opportunity zones, the amount of capital deployed and the appreciation of that capital.

Currently, there is no public reporting requirement.